The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership (23 page)

Read The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership Online

Authors: Yehuda Avner

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #Politics

Begin seemed dumbfounded.

Uncharacteristically animated, unable to resist his own extraordinary account of what was going on in the back channels of his diplomatic life, Yitzhak Rabin told how when he had gone to Kissinger with Golda Meir’s letter to be transmitted to the president he decided to put his cards firmly on the table. “I said to Kissinger outright,” he told Begin, “that we were embarking on a full-scale public relations campaign against the Rogers Plan and that I, personally, would do everything in my power, within the bounds of the American law, to arouse American public opinion against the Administration because of it.”

“Strong words!” said Begin.

“Strong enough to crack Kissinger’s sangfroid.”

Rabin reopened the locked drawer and took out a yellow legal pad whose top page was filled with his own scribble. “This,” he explained, waving the pad, “is a verbatim record of how Kissinger answered me. I wrote it down straight after the meeting. He said ‘

What is done is done, but under no circumstances, I beg you, under no circumstances, should you attack the president. It would mean a confrontation with the United States, and that’s the last thing Israel can afford. The president has not spoken about the Rogers Plan, so his name is not associated with it. He has given Rogers a free hand. But as long as he, himself, is not publicly committed to it, you have a chance to take action. How you act is your affair. What you say to Rogers or against him are for you to decide. But I advise you again, don’t attack the president!’”

20

Rabin, more spirited than ever, added pepper to his tale by saying, “And then Kissinger sprang a huge surprise on me. As I was about to leave, he said, ‘The president would like to shake your hand.’ ‘You’re joking,’ said I. ‘No I’m not,’ said he. ‘Shall we go in and see him now?’ I was totally bowled over. For an ambassador of a tiny country to see the president of the United States at a moment’s notice

–

unheard of!”

“And then what?”

“We crossed the street to the Executive Office Building to a room where Nixon closets himself when he wants peace and quiet. When we entered he was on his feet talking to Melvin Laird, the Defense Secretary. The president welcomed me, and said”

–

again he referred to the scribbled page

–

“ ‘I understand this is a difficult time for us all. I believe that the Israeli Government is perfectly entitled to express its feelings and views, and I regard that with complete understanding.’ Then, to Kissinger, he said, ‘Where do matters stand on Israel’s requests for arms and equipment?’ Kissinger replied in his usual evasive manner, ‘We are in the midst of examining Israel’s needs now.’ The president, who was in a most genial mood, said, ‘I promised that we would not only provide for Israel’s defense needs, but for her economic needs as well.’ To which Kissinger responded, ‘The examination covers both.’ Then Nixon turned back to me and said, ‘I can well understand your concern. I know the difficulties you face in your campaign against terrorist operations, and I am particularly aware of your defense needs. In all matters connected with arms supplies, don’t hesitate to approach Laird or Kissinger. Actually it would be better if you approached Kissinger.’ Those were his exact words.”

“How long did this go on for?”

“Seven or eight minutes. Back in the car I scribbled everything down, and could only wonder at the meaning of it all. Were Nixon and Kissinger trying to prove to me

–

and through me to our Government

–

that the president’s attitude toward Israel differed from that of his State Department? Was he inviting me to drive a public wedge between them, or merely trying to ensure that we keep our fire far away from the White House? Whatever it was, it was as good a go-ahead as I could possibly get. Check those Pink Sheets. You won’t find a single word against Nixon or against Kissinger, or against the Administration as such, only against Rogers and his State Department. And I can tell you, the man is already in retreat. A columnist quoted Kissinger the other day as saying to Nixon, ‘Rogers is like a gambler on a losing streak. He wants to increase his stakes all the time. The whole thing is doomed to futility.’”

And, indeed, it was. The Rogers Plan died a slow but certain death, and Ambassador Rabin could pat himself on the back for having helped make it wither. As a result people in Washington began to take a closer look at this fellow

–

the envoy who consorted constantly with Kissinger and who occasionally met with the president himself.

Given his vast experience in military affairs, Rabin was a frequent guest at the Pentagon, too. Senior officials and generals sought his strategic assessments. On one occasion, in March 1972, Kissinger invited him for a private chat to solicit his views on the possible direction of an anticipated North Vietnamese offensive. Mulling over maps, Rabin pointed to a spot where the United States forces appeared particularly vulnerable, and said, “Your forces are not strong enough on this side, and my guess is the North Vietnamese will go for a flanking movement and try to encircle you through there.”

“You’re the only general who seems to think that way,” said Kissinger skeptically. And then, when the offensive Rabin had predicted began, he confronted his top brass and snidely ribbed, “The only general who forecasted precisely the direction of the enemy’s thrust was the Israeli ambassador to Washington.”

In truth, no other envoy succeeded in cultivating so much trust and respect in so short a time among the highest levels of the Administration, the all-powerful media, the dominant string-pullers on Capitol Hill, and the influential Jewish organizations. In the course of Rabin’s five-year tenure he succeeded in turning a modest embassy into a prestigious address, so much so that in December 1972, as he wound down his tour of duty,

Newsweek

magazine crowned him “Ambassador of the Year.”

I, by now back in Jerusalem, sent him a short congratulatory note, to which he replied on 19 December 1972 in his typical candid and blunt fashion:

I confess it is a nice feeling to wind up one’s tour of duty with ‘flying colors,’ particularly in view of the vilification campaign which was, and still is, being conducted against me by the foreign minister [Abba Eban] and his associates in the Foreign Ministry. Over the last two years the Foreign Ministry has done things unheard of in any self-respecting, enlightened society, and this for the sole purpose of damaging me personally.

I don’t need a write-up in

Newsweek

to know I’ve done a good job here. The problem is that our world is something of a dumbbell. Jews are still stricken with an excessive exile complex [a euphemism for a hang-up], and that goes for much of our Israeli public, too. They are forever in need of outside recognition to acknowledge that an Israeli, and even Israel itself, can actually succeed in accomplishing something worthwhile. And it is from that standpoint alone that the

Newsweek

write-up

–

which I did nothing to initiate

–

can be considered significant.

Meanwhile, the situation here is unchanged. There has been a deterioration in the U.S. prospect of achieving an early settlement in Vietnam…. At the same time, I have no doubt that the fate of the American involvement in Vietnam is a foregone conclusion and will be sealed in the course of 1973. Be that as it may, we have meanwhile gained precious time, which will bring us to the summer without any particular [imposed] initiative.

The next time I saw Yitzhak Rabin was over coffee in Jerusalem’s Atara Café. It was shortly after his return from Washington, in March 1973, and he was grumpy. “Three times three different party big shots have promised me a cabinet position,” he told me, “but nothing has come of any of them. It seems that if I want to go into politics I’ll have to do it the hard way

–

doing my own campaigning

–

and not rely on Golda Meir’s promises.”

“Golda herself actually promised you something?” I asked.

“Once she did, but now she tells me there’s nothing available. I’ll have to wait until after the elections in October 1973. Then she hopes to find me a slot. That’s as far as Golda was ready to go.”

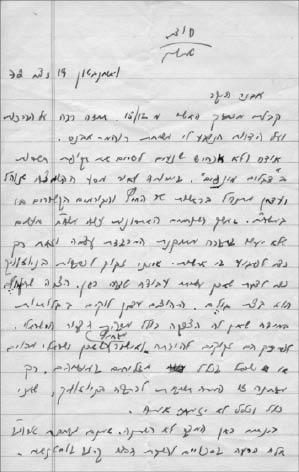

Opening page of letter from Ambassador Yitzhak Rabin to author quoted in the text

pp.

195–196, bitterly complaining of the attitude of the foreign ministry under Abba Eban while serving as ambassador to Washington, 9 December 1972

1969–1974

1898

–

Born in Kiev, Ukraine.

1906

–

Migrates with family to Milwaukee, U.S.A.

1917

–

Graduates teachers training college and marries Morris Myerson.

1921

–

Emigrates to Palestine; joins Kibbutz Merhavya.

1924

–

Leaves kibbutz and becomes leading figure in the Israel Labor Movement.

1938

–

Separates from husband.

1948

–

Israel’s ambassador to the Soviet Union.

1949

–

Appointed minister of labor.

1956

–

Appointed minister of foreign affairs.

1966

–

Appointed secretary-general of the Labor Party.

1969

–

Appointed prime minister.

Key Events of Prime Ministership

April 1969

–

War of Attrition along the Suez Canal.

1970

–

American initiative for ceasefire; Menachem Begin resigns from her national unity government.

October 1973

–

Confronts Austrian Chancellor Bruno Kreisky over Soviet Jewish emigration to Israel.

October 1973

–

The Yom Kippur War.

1974

–

Resigns the premiership; is succeeded by Yitzhak Rabin.

1978

–

Dies at the age of 80.

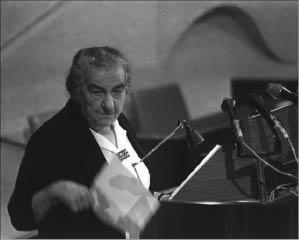

Photograph credit: Moshe Milner & Israel Government Press Office

Prime Minister Golda Meir addressing the Knesset, 10 March 1974

Changing of the Guard

When, on 7 March 1969, the Labor Party Central Committee elected Golda Meir as Levi Eshkol’s successor

–

and Israel’s first woman prime minister

–

she sobbed uncontrollably, and she made a point of saying so in her memoirs written six years later:

I have often been asked how I felt at that moment, and I wish I had a poetic answer to the question. I know that tears rolled down my cheeks and that I had my head in my hands when the voting was over, but all that I could recall about my feelings is that I was dazed. I had never planned to be prime minister; I had never planned any position, in fact…I only knew that now I would have to make decisions every day that would affect the lives of millions of people, and I think that is why perhaps I cried.

21

I, a junior member of her staff, never saw her cry, though there were enough excruciating moments ahead when she had reason to do so. But Golda was made of sterner stuff. She was, as Abba Eban put it, a “tough lady with a domineering streak.” Her “talent lay in the simplification of issues. She went straight to the crux and center of each problem…. When officials analyzed the contradictory waves of influence that flowed into decision-making, she tended to interrupt them with an abrupt request for the bottom line. The quest for the simple truth is not easy when the truth is not simple.”

22

For her, the bottom-line practical answers were rooted, first and foremost, in the creed of her Labor Zionist faith

–

a faith that never wavered even when it was rebuffed time and again by her fellow socialist delegates at the United Nations

–

the very same comrades with whom she happily hobnobbed in the committee rooms of the Socialist International, the worldwide association of social democrat, socialist, and labor parties, in which she played an active part. So she would oftentimes brood and be bitter, prowling the length of the carpet, arms rigid, head down, talking non stop in whole paragraphs about Israel’s isolation in the international community because representatives of socialist countries behaved no differently toward the Jewish State than their reactionary counterparts, allowing anti-Israel resolutions to pass wholesale.

“I look around me at the United Nations,” I once heard her say, “and I think to myself, we have no family here. Israel is entirely alone here, less than popular, and certainly misunderstood. All we have to fall back on is our own Zionist faith. But why should that be? Why? Why?”

Strangely, Golda Meir made no attempt to answer her own earth-shattering question: why, indeed, was the Jewish State the perennial odd state out in the family of nations?

I, having returned from Washington in the fall of 1972 to head up the prime minister’s Foreign Press Bureau, was quick to realize that what she said of foreign relations very much applied to the foreign media as well: Israel was constantly being singled out by the press. On an average day, the Jewish State played host

–

still does

–

to one of the largest foreign press corps in the world. This seemed to me to reflect not mere international interest, not mere international curiosity, not mere international preoccupation; but an outright international obsession.

Foreign correspondents to Israel habitually camp out at the American Colony Hotel which, by Jerusalem standards, stands in a class of its own. Once a nineteenth-century Pasha’s palace, it is suffused with an aura of understated elegance and a patrician grace, coupled with an aroma of British imperial stateliness. One can imagine Lawrence of

Arabia

chatting with General Allenby in its leafy courtyard, or Agatha Christie sipping tea with Sir Ronald Storrs in its spacious,

high-windowed

Pasha’s Room upstairs.

With the passage of the years, as the tears of the Jewish-Arab conflict fell ever more heavily over the land, the international press corps found this genteel and very Gentile relic of cozier times conducive to their purposes. The American Colony Hotel is well situated on the seam between Jerusalem’s east and west and, by common consent, its well stocked and companionable bar has long been designated as a kind of neutral watering hole where Jews and Arabs can meet foreign correspondents

–

and each other

–

free of constraints.

The first time I visited the place was the day after I started my new job, to keep an appointment with an independent television newsman from Chicago. Finding no sign of him in the lobby I sauntered upstairs to the Pasha’s Room, where an Arab wedding was getting into stride. Streamers and balloons festooned its ornamental domed interior. It was filled with dark-suited males and virtuously clad females, socializing separately. A trio consisting of an accordionist, a saxophonist, and a mandolinist were playing soft Oriental melodies. When they switched beat to pound on tabors the men stepped onto the dance floor to perform the dabke dance, each resting a hand on his neighbor’s shoulder, stomping in unison to the staccato tempo of the little drums, chanting praises to Allah.

Two middle-aged fellows with drooping mustaches, in dazzling white tasselled keffiyehs

–

the fathers of the bride and groom presumably

–

were heaved onto hefty shoulders and, to the shrill ululations and the clapping hands of the women, gyrated in extreme excitement, yelping and flailing the air with finely wrought ornamental daggers. Faster and faster they twirled, and only when the music rose to a crescendo and sounded an authoritative final chord did the dervish-like swirling ease and the ovation fade.

Spotting me, the man whom I had come to meet signaled recognition and, dabbing a sweaty brow, swiftly made his way to the door where I was hovering. He apologized for not having met me in the lobby as arranged, and panted, “It’s this dancing. I lost all sense of time. Forgive me.”

He was conspicuous in a gaudy, awning-striped shirt and a polka-dot bow tie, and his name was as chummy and as ebullient as his face: Buddy Bailey.

Over a drink in the bar, Buddy told me he had been commissioned to produce a television feature on Golda Meir and the future of Jerusalem, and that his Palestinian cameraman was the father of the bride upstairs, hence his hop, skip and jump on the Pasha Room’s dance floor. What he wanted from me was assistance in arranging a couple of interviews, one with Prime Minister Meir, if possible, and also some insights into present-day Jerusalem.

Buddy Bailey admitted to only the most cursory knowledge of his subject, confessing that he was far too much on the go to be able to do much homework. “I know it sounds crazy,” he owned up, “but I’ve only the vaguest recollection of your Six-Day War, and how you came to be in Arab East Jerusalem in the first place.”

“Can I recommend a book or two before you start production?” I asked.

He sounded shocked. “Me

–

a book? I don’t have time for books. Guys like me have to rely on guys like you for information.”

“So how do you hope to produce

–

?”

“You see those guys over there?” He stopped me, pointing to a group of fellow journalists. “How many of those people do you think ever do real research? Go on, ask them! Ask them how many know anything about the history of Zionism, or how the conflict began, or how you came to be in the West Bank. Go on, ask them.” He was growing insolent in defense of his ignorance. “Ask them how many know your language

–

even those posted here. I bet not a one. All we journalists are slaves to all-news-all-the-time deadlines. We live by them, from one to the next. Who’s got the time to do research? Our bosses want human action, not complicated facts.”

“So how on earth do you dig up your information?” I asked naively.

“By poking our noses where your television cameras and newsmen poke theirs, and by picking the brains of guys like you, and by getting tips and gossip from Arab locals, like my cameraman upstairs.”

Suddenly, he swiveled around. A hand had descended on his shoulder from behind, and he called out in delight, “Talk of the devil! Fayez

–

it’s you! I was just talking about you. Join us. Wedding going okay?”

Fayez threw us a dazzling smile, dabbed his brow with a corner of his keffiyeh, and heaved mischievously, “I’ve been dancing far too much with my daughter, the bride, so I sneaked out to cool off and indulge in a little forbidden stimulant while my guests upstairs are not watching.”

“A Scotch here, please, barman,” called Buddy Bailey, snapping his fingers. “Black Label. Make it a double.”

Fayez downed half his drink in a single swig, checking the room to make sure no one of his faith was catching him in the act, and downed the rest. Relaxed now, he chuckled, “Forgive my agitation. It’s the excitement of the wedding.”

“Fayez,” said Buddy Bailey cheekily, throwing him a wink. “I have a question. I’ve been telling Yehuda here how tough it is for a foreign correspondent like me to get a grip on the conflict between you two. What do you think the chances are of you and Yehuda making up and shaking hands, eh?”

The man sounded a hiccup, “What do you mean, making up, shaking hands?”

“Peace. Making peace. Letting bygones be bygones.”

Fayez looked me up and down, lazy laughter in his eyes, and said in perfect Hebrew, “You and me

–

peace?”

He removed his keffiyeh, scrubbed his curly graying hair with his knuckles, pulled back his shoulders, lifted his jaw, and in a voice warped with whisky, said,

“

Habibi

–

My friend

–

it won’t work. Our genes are too different. You Jews come from everywhere. You are mongrels. We Arabs come from the desert. We are thoroughbreds. You think in subtleties, we think in primary colors.”

“What do you mean

–

primary colors?” I asked.

He placed a hand on my shoulder, whether in fellowship or to steady himself I could not tell, and rambled on, “Primary colors means that there is nothing subtle about the desert. Everything there is in the extremes

–

blazing hot days, icy cold nights, arid sands, luscious oases. That’s why we Arabs are most at ease in the extremes. It’s in our blood. We can be over-generous one minute, over-greedy the next, hospitable one minute, cut-throat the next, fatalistic one minute, straining at the leash the next. And at this minute”

–

he had me by the hand

–

“I’m in a highly hospitable mood, so please come upstairs and join my daughter’s wedding. No? You have other things to do? Fine! Then I shall go alone,” and off he went, walking with the over-disciplined stride of a man under the influence.

“What was that supposed to mean?” asked Buddy, mystified.

Bemused myself, I answered, “I’m not at all sure. I’m not sure how much was him doing the talking and how much was the drink. But what I do know is that when it comes to our conflict they do appear most at ease in the extremes.”