The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership (68 page)

Read The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership Online

Authors: Yehuda Avner

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #Politics

“If only you’d allow me to

–

”

“In nineteen forty-six, in this house where we are sitting today, there lived a British general whose name was Barker. Today, I live in this house. When we fought against him he called us terrorists, and yet we continued our struggle. After we blew up his headquarters in the King David Hotel, Barker said, ‘You can punish this race only by hitting them in their pockets,’ and he issued an order to his British troops that all Jewish coffee shops were to be out of bounds. ‘Hit them in their pockets,’ he said. That was the Barker philosophy. Well, I now understand why the whole great effort in the Senate to win a majority for the arms deal with Saudi Arabia was accompanied by such an ugly, anti-Semitic campaign.”

“Not so

–

”

“Yes so. First came the slogan,

‘

Begin or Reagan!

’

–

the inference being that to oppose the deal with Saudi Arabia was tantamount to supporting a foreign prime minister while being disloyal to the president of the United States. Are such eminent senators as Kennedy, Jackson, Moynihan, Packwood, and of course Boschwitz, who expressed opposition to the deal, disloyal citizens? Are they? Then came another slogan: ‘

We will not allow the Jews to determine the foreign policy of the United States

.’ Well, let me tell you something, Mr. Ambassador: no one will frighten the great and free Jewish community of the United States. No one will succeed in intimidating them with anti-Semitic propaganda. They will stand by us. This is the land of their forefathers, and they have a right and a duty to support it.”

“Mr. Prime Minister, you surely don’t believe that

–

”

“There are those who say the Golan Law adopted by the Knesset has to be rescinded. The word ‘rescind,’ Mr. Ambassador, is a concept from the time of the Inquisition. Our forefathers went to the stake rather than rescind their faith. We are not going to the stake, Mr. Ambassador. Thank God, we have enough strength to defend our independence and defend our rights. Rescinding the Golan Law

–

”

“We are merely suggesting a review

–

”

“Rescinding the Golan Law, which is what you would have us do, does not depend on me. It depends on the Knesset. And it is my firm belief that there is not a man alive who can convince the Knesset to annul this law. So please tell the secretary of state that the Golan Law shall remain in force. Nothing and nobody can bring about its abrogation.”

Lewis had clearly had enough. Dispensing with even the pretense of nicety, he shot back, “Mr. Prime Minister, you have not allowed me to explain what I have to say. I shall certainly deliver your urgent and private message to the president. But in the meantime, I have a message for you: between friends and allies there should be no surprises. There should be consultations by either party on issues which affect the other’s interests.”

“Correct, but the surprise on this occasion was because we did not want to embarrass you, by putting you in a predicament vis-à-vis the Arab capitals with which you have ties. Had we told you beforehand what we intended to do, you would have said no. We did not want you to have to say no, and then proceed with the legislation, which is what we would have done under all circumstances.”

Faced with this unending barrage, which to the ambassador seemed somewhat hyperbolic and, in part, even paranoid, he saw no point in carrying on, so he took his leave and set out on the drive back to his Tel Aviv Embassy, to cable off his report. On the way out of Jerusalem, he switched on the radio, and what he heard flummoxed him totally.

“I don’t believe this is happening,” he said morosely to his note-taker. “Is this Begin’s idea of a private and urgent message to the president of the United States? Boy, is Washington going to have something to say about this.”

What he was hearing was the voice of the cabinet secretary, repeating almost word for word, in English, for the benefit of the foreign correspondents assembled outside Begin’s residence, the fieriest of all the passages of Begin’s harangue.

The White House was livid. It deemed the language of the prime minister’s message intemperate, it deemed its tone improper, and it deemed the treatment of its envoy an affront to America itself. That same day, President Reagan was seen heaving a huge sigh of bewilderment upon reading the report, scratching his head, and wheezing, “Boy, that guy Begin sure does make it hard to be his friend.”

Shortly thereafter, Ambassador Lewis escorted a senior senator to meet Mr. Begin and assess the frozen situation. When the meeting was done, the ambassador said, “Mr. Prime Minister, there is something I wish to talk to you about. It concerns me personally.”

Begin gave him an amiable look, and said, “Go ahead, Sam. What’s on your mind?” There was not the slightest hint of guile in his voice.

“It has to do with the handling of the urgent and private message you asked me to deliver to the President,” said Lewis. “The fact that you authorized the release of that message to the media almost immediately after I had left you, was, to put it mildly, a violation of every diplomatic norm and practice. And the way you did it made me feel I was being treated like an idiot.”

“But surely, you realize there was nothing personal in what I said or did,” said the prime minister, surprised at Lewis’s rancor. “I considered your government’s act of such grave national consequence that I felt compelled to fully inform our people of our stand, there and then, to make it plain that we, too, have red lines.”

“Yes, but hardly had I left Jerusalem when I heard your spokesman on the radio quoting what you’d said to me almost word for word, in what was supposed to have been a personal message to the president.”

Begin pursed his lips in thought, and said, “I simply never thought of it in that light, Sam. My one consideration was that, given the sharpest difference of views we had

–

and still have

–

on a matter so vital to our future as the Golan Heights, I felt our public had a right to know exactly what was said and where we stood. I apologize if I embarrassed you personally. Forgive me, please.”

The tone of contrition in the prime minister’s voice filled Sam Lewis with a sense of uncommon bemusement. Never had he thought this proudest of men capable of such humble apology.

90

[

1

]

A summit of Arab leaders held on 25 November, 1981.

Pacta Sunt Servanda

There were those who would describe what occurred subsequently in the Reagan-Begin relationship as a deep freeze, others as a temporary lapse. The first spoke of rupture and schism, the others of a mere wobble. But the relationship recovered somewhat when, within Israel itself, a violent convulsion occurred: in preparation for a final withdrawal of Israeli troops from Egyptian territory, the Jewish settlements in Sinai were dismantled. Some in Washington had feared that, as a consequence of Sadat’s assassination, the uncertainty surrounding the appointment of his successor, Hosni Mubarak, and the prospect of a surge in Islamism, Begin might well have second thoughts and seek a last-minute pretext not to withdraw. But when the day came for the final phase of the peace treaty to be enacted

–

April 25 1982

–

withdraw he did.

“

Pacta sunt servanda

–

agreements must be kept, treaties must be carried out,” said Begin, with severe conviction. “It is the golden rule of international law. The observance of an international agreement is an absolute duty. If one side carries out its part, it obligates the other side to do the same. If one side commits a breach, it entitles the other side to do the same.”

We were in his apartment, where he was now managing to hobble about with the help of a cane, which was what he was doing now, after having perused letters and other documents which I had brought to him for approval. But his mind was elsewhere. I could see it in his eyes, which were clouded with sadness as he picked up a week-old newspaper and stared at the photograph which dominated its front page. It portrayed the wrenching spectacle of Israeli soldiers scaling barricaded buildings on ladders, forcefully evicting protesting inhabitants and other anti-withdrawal diehards from Yamit, a brand-new town of pristine beauty that had been built out of the sand dunes of Sinai’s Mediterranean coastline. But Yamit had to go, if the peace treaty was to stand.

Begin put the paper down, but I could sense that he was still seeing that photo. “What a tragedy,” he mumbled. “What a trauma.” And then, affirming the validity of forcefully evacuating and destroying Yamit, he said with utter finality, “We have to honor our signature. We must remain true to our commitment.

Pacta sunt servanda!

”

Fifteen years of Israeli presence in Sinai would end at noon the following day

–

fifteen years that had involved incessant toil, infrastructural investment, oil exploration, desert reclamation, and widespread settlement construction. At noon, the last Israeli flag would be lowered in a low-key military ceremony at the resort which Israel had begun building, Ophira, on a spit of land abutting the Straits of Tiran. As of the next day it would revert to its original Arabic name: Sharm el-Sheikh.

The operative paragraph of the

IDF

order of the day read:

“We are leaving Sinai primarily for our own sake

–

for the sake of our children and future generations, to try and find a way other than warfare

–

a way of the outstretched hand of peace.”

Beneath these words a military intelligence officer had scribbled:

“The Egyptians have distributed national flags to the locals, and it is expected that as our contingent pulls back to the Israeli frontier they will be followed by cheering, jeering and waving Bedouin, who will slaughter sheep along the roadside in celebration.”

“So be it,” sighed the prime minister, reading the note. “Let them slaughter sheep to their heart’s content. Were Sadat alive things might have been a little different. Time alone will tell.” And then, almost fatalistically, “Mubarak is certainly no Sadat. With Anwar, whatever our differences, we developed a very close relationship, based, in the first instance, on mutual trust. We used to open our hearts to one another. Often we would speak about our beliefs and our ancient traditions, and our experiences, and how they impacted on our lives and made us what we are. And he used to tell me things which he told nobody else, including the fact that he did not hold his Mubarak, his vice president, in the highest esteem.”

Leaning on his cane, he limped back to where he’d been sitting, and in a voice permeated with nostalgia, said, “Our families became very close. We were drawn to one another

–

our wives, our children. His family became like my own. And when Anwar was assassinated we grieved, oh how we grieved. I said to Jehan, and to Anwar’s son and daughters, I said, and I meant every word of what I said, that his death was a loss to the world, to the Middle East, to Egypt, to Israel, and to my wife and to myself personally. We invited all the family to Israel. The invitation still stands. They will be our personal guests.”

“And how will Mubarak take to that, you maintaining such a close personal relationship with Mrs. Sadat?” I asked.

Begin gave me an impatient shrug, as if not wishing to even contemplate the implications of my question and, instead, rambled on in a husky, distant voice, “I trusted Anwar. By the time it came to implementing the clauses of the peace treaty, I sensed that despite all the ups and downs he genuinely wanted this to be a reconciliation between our peoples, not simply a contract between our governments. We once said to each other that our lives are short, but the peace must surely outlive us. One day we were sitting together on his terrace in Alexandria, just the two of us, he puffing on his pipe and looking out to sea, and he said, ‘You know, Menachem, there will come a time when I will no longer be president of Egypt.’ And I said to him, ‘You know, Anwar, there will come a time when I will no longer be prime minister of Israel.’ And then we laughed, and embraced, and said to one another with true affection that while we will inevitably go the way of all flesh, our nations will never pass away, and neither, with the grace of God, will the peace.”

Eyes glittering, fixed on images from an unforgettable time and place, he continued his reminiscences. “Ah, remember El Arish? Remember how the war invalids, ours and theirs, casualties of five wars, met and embraced? One had to see it to believe it

–

to see with one’s own eyes that such reconciliation was possible: soldiers, some without hands, some without legs, some blinded, maimed for life, hugged and kissed, and cried out to each other over and over, ‘Never again war! No more war ever again.’ I doubt if such a thing has ever happened anywhere, at any time, in any other country.”

And then, beseechingly, like a prayer, “May the Almighty induce in Hosni Mubarak’s heart the belief in this sort of peace

–

the peace which Anwar and I believed in.”

91

With that, he leaned across the table, took pen and paper in hand and began to write a note to Jehan Sadat with intense concentration:

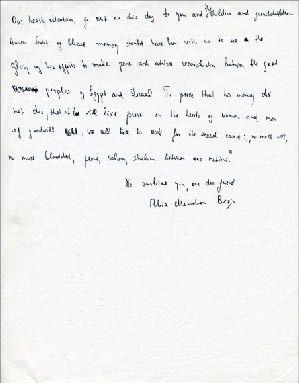

Our hearts, Madame, go out on this day to you and your children and grandchildren. Anwar Sadat, of blessed memory, should have been with us to see the glory of his efforts to make peace and achieve reconciliation between the good peoples of Egypt and Israel. To prove that his memory did not die, that it will live on forever in the hearts of women and men of goodwill, we have to work for the sacred cause: “No more war, no more bloodshed, peace, salaam, shalom, between our nations.”

We embrace you, our dear friend,

Aliza and Menachem Begin

He laid down his pen, handed me the page, and said, “Try and make sure our ambassador in Cairo delivers this personally to Mrs. Sadat as soon as possible.”

Personal message from the Begins to Mrs. Jehan Sadat on the day of Israel's final withdrawal from Sinai, 25 April 1982