The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership (7 page)

Read The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership Online

Authors: Yehuda Avner

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #Politics

Survivors lucky enough to have some form of legal entry document gathered at the foot of the steep iron stairway leading from steerage up to the promenade deck, watched by paratroopers. Everybody was pressing forward against each other. Mothers held babies in tightly-wrapped bundles and fathers clutched children by the hand or high on their shoulders, promising them all manner of punishment if they dared misbehave. Faces strained upward bearing looks of anxious excitement, waiting to be told they could move to the upper deck to be processed and cleared for landing.

Hanging around in poses of anxiety in the rear of the stern were the illegals, those with no useful valid documents at all, waiting to be arrested.

“Jesus, how they stink,” spat a beefy sergeant, his features twisting as if he had bitten into a lemon. Then, a cry of alarm went up.

A short, skeletal, black-clad yeshiva boy with wild eyes and deathly-white skin burst out of a covered lifeboat, jumped headlong into the steerage crowd, and darted to the rail, readying to jump.

The sergeant dashed after him, his face angry, his rifle cocked.

“’Ere, none of that,” he bellowed. “Nobody’s jumping this ship. Get back down ’ere.” He grabbed Yossel’s foot and broke his balance. Other soldiers ran forward, and Yossel kicked the sergeant away. He spurted back toward the crowd of shouting refugees who were now scattering in panic, abandoning their belongings. Fellow illegals took strength from Yossel’s escape attempt, burrowing their way through the luggage, and shoving bags and sacks in the way of the pursuing soldiers. “Keep going, Yossel!” some cried. “Jump for it!”

Yossel dodged and leaped over the strewn baggage and between groups of startled passengers who parted to let him through. Not knowing which way to turn as his pursuers closed in, Yossel zigzagged around the deck. Two paratroopers crouched, ready to jump him in a rugby tackle, but he was too quick for them. Deftly, with unsuspected athleticism, he leaped around them and careened this way and that, desperately looking for an avenue of escape. Finding none, he fled up the stairway and up to the bridge house, straight into the grip of the outraged Greek captain who kicked him hard in the ribs and felled him.

Yossel made no further move to escape. His chest heaved and his nose bled. Three soldiers, expressionless, aimed their rifles directly at him while another shackled him with handcuffs.

“Hey, hotshot,” Yossel Kolowitz yelled out to me through swollen lips, as he was hustled toward the gangway, “Begin will soon be kicking out these British bastards, and then – ”

A single blow to the head from the beefy sergeant cut him short, and off he was dragged to a police van, to be driven to some barbed wire detention camp, God only knows where. Once the van disappeared off the dock, Yossel Kolowitz quickly became a vanishing memory, as a British official stamped my passport and, full of excitement, I disembarked from the

Aegean Star

and caught a bus to Jerusalem. The date was Friday, 14 November 1947.

Jerusalem! Its individuality is unique.

Something deep stirred within me when I entered it. I did not know what to call it then; I do not know what to call it now. It has the depth of an old masterpiece whose simplicity veils an immense sophistication. And like great music, its composition

–

the ancient and the modern, the religious and the secular, the Jews, the Muslims, the Christians, and their multiple tones and variations, all somehow synchronize into an incongruous harmony.

Yet, it is said that Jerusalem is the most disputed city in history; that more blood has been shed for Jerusalem than for any other spot on earth. Century after century, armies have fought to conquer and subjugate it: the Assyrians, the Babylonians, the Greeks, the Persians, the Syrians, the Romans, the Saracens, the Franks, the Arabs, the Turks, the Europeans, and again the Arabs. Nonetheless, throughout its three-thousand-year-long history Jerusalem has been capital to no one but the Jews.

I first set eyes on Jerusalem from afar, toward the end of the day, as the bus carrying me from Haifa snaked its way up the tortuous, twisting gorges of the Judean Hills. The lowering sun cast vivid rays across a sky aflame with scarlet and crimson. My Manchester eyes, attuned to cloud and rain, had never seen such a sky. As we arrived near the city center, Jerusalem’s masonry seemed to suck up the hues, giving the walls a translucent, golden appearance. The bus slowed as it approached the bustling intersection of Jaffa Road and King George Street, where a sinewy Arab constable, perched on a pedestal and dressed in short pants and a

lambswool

fez, directed the traffic with a truncheon. When suddenly two sharp retorts rang out in quick succession, he began blowing a whistle and swinging his arms around like a windmill, doing his bungling best to halt the pre-Sabbath traffic so as to allow two English policemen to dart across the road, revolvers at the ready. Our driver agitatedly jumped up in his seat, and cried, “Look – the police! They’re chasing a man. The man’s throwing leaflets. He must be an Irgunist.”

Leaflets fluttered around the intersection like so many laundered kerchiefs blowing in the breeze. One adhered briefly to my window. It displayed a roughly-printed Begin broadside: “JEWS ARISE! FREE THE HOMELAND OF THE BRITISH OPPRESSOR!” The flyer was crowned by an emblem in the form of a rifle thrust aloft by a clenched fist and ringed by the motto, “ONLY THUS!” It was the insignia of the Irgun.

All keyed up, our driver stuck his head out of the window to get a clearer view. “Oh my God,” he gasped, “they’ve got him cornered. The poor fellow, he’s down. They’re beating him up. Oh, my God, he’s bleeding.”

People in the street were gazing in fright upon a young man

–

just a boy, really

–

lying prone on the opposite curb, his arms twisted behind his back, manacled. Blood oozed from a gash at the nape of his neck, staining the collar of his gray windbreaker. As he lay there, face down on his belly amid his scattered leaflets, his dark-blue beret askew on his curly ginger head, he kicked futilely at the British soldier who had him pinioned to the ground like a maimed steer.

The two English policemen with the revolvers came panting back and, gesticulating at the jammed traffic, barked orders to sort it out and open up a lane to let a police van through. They flung the handcuffed lad into this mobile dungeon, and soon the intersection returned to normal.

It had all been so public, so anonymous, so unbargained for, so fast, that I was transfixed, more stupefied than mortified. Here I was, less than twenty-four hours in the country, and already I had been witness to two clashes involving British police and soldiers accosting, battling, beating, and arresting two young, desperate, and reckless Begin boys. What seemed most alarming to me was their ruthless efficiency. Soldiers and policemen seemed to be on the prowl everywhere, primed for action, pouncing without quarter.

When the bus rolled on across the intersection down Jaffa Road, and passed what looked like a police station, I caught sight of a wall poster that sent a shiver down my spine:

WANTED: MENACHEM BEGIN DEAD OR ALIVE

TEN THOUSAND POUNDS REWARD

FOR INFORMATION

LEADING TO HIS CAPTURE

Staring grimly at me from the heart of the poster was a grimy, unshaven, coffin-like face with piercing black eyes framed in spectacles, wearing the desperate look of a man on the run.

That evening, after swiftly unpacking into cramped lodgings in the leafy suburb of Beit Hakerem where the

Machon

was housed, I rushed over to the nearby synagogue for Shabbat-evening prayers. Upon my return, I met my fellow students as we sat down around a table laden with Shabbat fare. There were twenty-four of us, all from

English-speaking

countries, and all keenly braced for a year-long intensive encounter with the Hebrew language, Hebrew culture, Jewish history, Zionist ideology, and all manner of other disciplines indispensable to a first-rate youth leader with aspirations to become a first-rate fighting pioneer.

Inevitably, by dinner’s end the conversation had turned to the growing turbulence in the country, and since we represented virtually every shade of Zionist politics, the exchange quickly escalated into an argument. Two of the participants, one from Liverpool and one from Cleveland, almost came to blows over the animosity between the Hagana and the Irgun. The row was only defused when someone struck up a lively melody which soon swelled into a sing-along of patriotic songs which we all bellowed in unison at the tops of our voices.

Going to bed that night I could not erase the haunting image of Menachem Begin’s face which I had seen on the “Wanted: Dead or Alive” poster. It was a ghastly introduction to Jerusalem. But it was representative of the desperate situation in Palestine in those final months of the Mandate. Like a Greek chorus frenetically chanting the finale of the final act of the final showdown, the gory Palestine opus climbed to a clamorous crescendo. The violent and ugly tit-for-tat rocketed sky-high

–

the shots in the night, the road mines, the sabotage, the threats, the kidnappings, the truck bombs, the killings. Increasingly, British forces imposed severe self-protective limits upon themselves. Personnel were ordered to move about in groups of no less than four. Cinemas, cafés, indeed whole districts, were placed out of bounds. Scores of Jewish families were forcibly ejected from their homes to make way for British military personnel dependents, women and children, in newly designated security enclosures surrounded by soaring fences. Bit by bit, the authorities were locking themselves up into barbed wire ghettoes. This was the Palestine which I had reached, just in time for one of the most significant events of Jewish history: A despairing Britain threw in the towel and placed the whole frightful Palestine mess in the lap of the United Nations General Assembly, which, on 29 November 1947, voted to partition the bleeding and tattered country into a Jewish State and an Arab State.

November 29 was a Shabbat, so it was only in the early hours of the Sunday morning that we students at the

Machon

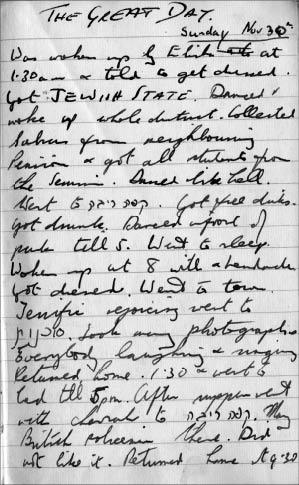

seminar heard the news. My diary entry of 30 November, headed in bold block letters “THE GREAT DAY,” reads:

Was woken up at 1:30

a.m.

and told to get dressed. Got JEWISH STATE! Danced and woke up the whole district. Danced like hell till 5 in the morning. Got free drinks. Got drunk. Went to sleep. Woken up at 8 with a headache. Got dressed. Went into town. Terrific rejoicing. Went to the Jewish Agency. Everybody laughing and singing and dancing. Returned home 1:30 and went to bed till 5. After supper went with

chevra

–

the pals

–

to Café Riva. Many British policemen there. Did not like it. Returned home at 9:30 and went to bed.

Two days later, on Tuesday, 2 December, at 11:30 in the morning, while in the middle of a Hebrew class, I was handed a telegram. It was from home. Unobtrusively, I opened it. It was a single ribbon of text. It said, “Mammy passed away peacefully in the night.”

I felt a sudden tightness in my throat and a shortage of breath. Numbly, I walked out and made my way to my room. It was all so unreal, like sleepwalking. I locked the door and sat on the bed, deadened. I tried to cry but couldn’t. I was too shocked and shaken to cry. I don’t suppose there is a right and a wrong way to grieve, but what was infinitely painful was sitting there alone, away from the family, and feeling the guilt of having left my mother hardly three weeks beforehand knowing she was desperately ill, and being absent now from her funeral. So I sat out the long seven days of mourning

–

the

shiva

–

alone. Fellow students at the

Machon

assembled each day to form a

minyan

–

the prayer quorum

–

enabling me to recite Kaddish, but otherwise I sat solitary in my room sharing my feelings with no one, just mourning my mother.

The sole, admittedly powerful distraction, was the news that Arabs everywhere were up in arms over the

UN

partition resolution. They were vowing to destroy the Jewish State at birth. Bugles sounded the call to arms. Bit by bit, skirmishes mutated into operations, operations into battles, battles into campaigns, and campaigns into full-scale warfare. By the end of the year, just a couple of months after I’d arrived in Jerusalem, the city was under an intensifying siege.