The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary (12 page)

Authors: Simon Winchester

Tags: #General, #United States, #Biography, #Biography & Autobiography, #Psychiatric Hospital Patients, #Great Britain, #English Language, #English Language - Etymology, #Encyclopedias and Dictionaries - History and Criticism, #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865 - Veterans, #Lexicographers - Great Britain, #Minor; William Chester, #Murray; James Augustus Henry - Friends and Associates, #Lexicographers, #History and Criticism, #Encyclopedias and Dictionaries, #English Language - Lexicography, #Psychiatric Hospital Patients - Great Britain, #New English Dictionary on Historical Principles, #Oxford English Dictionary

A

.

adj.

1

. Of words and expressions (after Horace’s

sesquipedalia verba

‘words a foot and a half long’, A. P. 97): Of many syllables.

B

.

sb.

1

. A person or thing that is a foot and a half in height or length.

1615

Curry-Combe for Coxe-Combe

iii. 113 He thought fit by his variety, to make you knowne for a viperous Sesquipedalian in euery coast.

1656

Blount

Glossogr

2

. A sesquipedalian word.

1830

Fraser’s Mag.

I. 350 What an amazing power in writing down hard names and sesquipedalians does not the following passage manifest!

1894

Nat. Observer

6 Jan. 194/2 His sesquipedalians recall the utterances of another Doctor.

Hence

Se:squipeda·lianism

, style characterized by the use of long words; lengthiness

It was also on a foggy day in November, nearly a quarter of a century earlier, that the central events on the other side of this curious conjunction got properly under way. But while Doctor Minor arrived in London on a wintry November morning and took himself to an unfashionable lodging house in Victoria, this very different set of events took place early on a wintry November evening, and in an exceedingly select quarter of Mayfair.

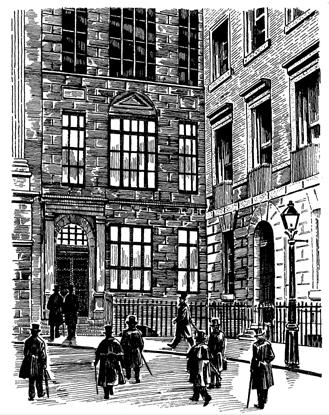

The date was November 5, Guy Fawkes Day, 1857, the time was shortly after six, and the place a narrow terraced house at the northwest corner of one of London’s most fashionable and aristocratic oases, St. James’s Square. On all sides were the grand townhouses and private clubs of the extraordinary number of bishops and peers and members of Parliament who lived there. The finest shops in town were just a stone’s throw away, as well as the prettiest churches, the most splendid offices, the oldest and most haughty of foreign embassies. The corner building on St. James’s Square housed an institution that was central to the intellectual lives of the great men who lived nearby (a role it still plays today, though happily in a somewhat more democratic world). It provided accommodation for what its admirers regarded then as they still do today the finest private collection of publicly accessible books in the world, the London Library.

The library had moved there twelve years before, from cramped quarters on Pall Mall. The new building was tall and capacious, and although today it is filled to bursting with many more than a million books, back in 1857 it had only a few thousand volumes and plenty of space to spare. So its committee decided early on to raise extra money by renting out rooms, though only, it was decreed, to societies whose adherents were likely to share the same lofty aims of scholarship as did the library itself, and whose members would be able to mingle happily with the aristocratic and often staggeringly snobbish gentlemen who made up the library’s own membership rolls.

Two groups were chosen: The Statistical Society was one, the Philological Society the other. It was at a fortnightly meeting of the latter, held in an upstairs room on that chilly Thursday evening, that words were spoken that were to set in train a most remarkable series of events.

The speaker was the dean of Westminster, a formidable cleric by the name of Richard Chenevix Trench. Perhaps more than any other man alive, Doctor Trench personified the sweepingly noble ambitions of the Philological Society. He firmly believed, as did most of its two hundred members, that some kind of divine ordination lay behind what seemed then the ceaseless dissemination of the English language around the planet.

God—who in that part of London society was of course firmly held to be an Englishman—naturally approved the spread of the language as an essential imperial device; but he also encouraged its undisputed corollary, which was the worldwide growth of Christianity. The equation was really very simple, a formula for undoubted global good: The more English there was in the world, the more God-fearing its peoples would be. (And for a Protestant cleric there was a useful subtext: If English did manage eventually to outstrip the linguistic influences of the Roman Church, then its reach might even help bring the two churches back into some kind of ecumenical—if Anglican-dominated—harmony.)

So, even though the society’s stated role was academic, its informal purpose, under the direction of divines like Doctor Trench, was much more robustly chauvinist. True, earnestly classical philological discussions—of obscure topics like “Sound-Shifts in the Papuan and Negrito Dialects,” or “The Role of the Explosive Fricative in High German”—did lend the society scholarly heft, which was all very well. But the principal purpose of the group was in fact improving the understanding of what all members regarded as the properly dominant language of the world, and that was their own.

Sixty members were assembled at six o’clock on that November evening. Darkness had fallen on London soon after half past five. The gas lamps fizzed and sputtered, and on the corners of Piccadilly and Jermyn Street small boys were still collecting last-minute pennies for fireworks, their ragged models of old Guy Fawkes—soon to be burned on bonfires—propped up before them. Already in the distance the whistles and crashes and hisses of exploding rockets and Roman candles could be heard, as early parties got under way.

Like the fire-frightened housemaids who hurried back down to the servants’ entrances of the great houses nearby, the old philologists, cloaked against the chill, scuttled through the gloom. They were men who had long since outgrown such energetic diversions. They were eager to get away from the sound of explosions and the excitement of celebration, and repair to the calm of scholarly discourse.

Moreover, the topic for their evening’s entertainment looked promising, and not in the least taxing. Doctor Trench was to discuss, in a two-part lecture that had been billed as of considerable importance, the subject of dictionaries. The title of his talk suggested a bold agenda: He would tell his audience that those few dictionaries that then existed suffered from a number of serious shortcomings—grave deficiencies from which both the language and—by implication—the empire and its church might well eventually come to suffer. For those Victorians who accepted the sturdy precepts of the Philological Society, this was just the kind of talk they liked to hear.

The “English dictionary,” in the sense that we commonly use the phrase today—as an alphabetically arranged list of English words, together with an explanation of their meanings—is a relatively new invention. Four hundred years ago there was no such convenience available on any English bookshelf.

There was none available, for instance, when William Shakespeare was writing his plays. Whenever he came to use an unusual word, or to set a word in what seemed an unusual context—and his plays are extraordinarily rich with examples—he had almost no way of checking the propriety of what he was about to do. He was not able to reach into his bookshelves and select any one volume to help: He would not be able to find any book that might tell him if the word he had chosen was properly spelled, whether he had selected it correctly, or had used it in the right way in the proper place.

Shakespeare was not even able to perform a function that we consider today as perfectly normal and ordinary a function as reading itself. He could not, as the saying goes, “look something up.” Indeed the very phrase—when it is used in the sense of “searching for something in a dictionary or encylopaedia or other book of reference”—simply did not exist. It does not appear in the English language, in fact, until as late as 1692, when an Oxford historian named Anthony Wood used it.

Since there was no such phrase until the late seventeenth century, it follows that there was essentially no such concept either, certainly not at the time when Shakespeare was writing—a time when writers were writing furiously, and thinkers thinking as they rarely had before. Despite all the intellectual activity of the time there was in print no guide to the tongue, no linguistic

vade mecum

, no single book that Shakespeare or Martin Frobisher, Francis Drake, Walter Raleigh, Francis Bacon, Edmund Spenser, Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Nash, John Donne, Ben Jonson, Izaak Walton, or any of their other learned contemporaries could consult.

Consider, for instance, Shakespeare’s writing of

Twelfth Night

, which he completed sometime at the very beginning of the seventeenth century. Consider the moment, probably in the summer of 1601, when he has reached the writing of the scene in the third act in which Sebastian and Antonio, the shipwrecked sailor and his rescuer, have just arrived in port and are wondering where they might stay the night. Sebastian considers the question for a moment, and then, in the manner of someone who has read and well remembered his

Good Hotel Guide

of the day, declares quite simply: “In the south suburbs at the Elephant/Is best to lodge.”

Now what; exactly, did William Shakespeare know about elephants? Moreover, what did he know of Elephants as hotels? The name was one that was given to a number of lodging houses in various cities dotted around Europe. This particular Elephant, given that this was

Twelfth Night

, happened to be in Illyria; but there were many others, two of them at least in London. But however many there were—just why was this the case? Why name an inn after such a beast? And what was such a beast anyway? All of these are questions that, one would think, a writer should at least have been

able

to answer.

Yet they were not. If Shakespeare did not happen to know very much about elephants, which was likely, and if he were unaware of this curious habit of naming hotels after them—just where could he go to look the question up? And more—if he wasn’t precisely sure that he was giving his Sebastian the proper reference for his lines—for was the inn really likely to be named after an elephant, or was it perhaps named after another animal, a camel or a rhino, or a gnu?—where could he look to make quite sure? Where in fact would a playwright of Shakespeare’s time look

any

word up?

One might think he would want to look things up all the time. “Am not I consanguineous?” he writes in the same play. A few lines on he talks of “thy doublet of changeable taffeta.” He then declares: “Now is the woodcock near the gin.” Shakespeare’s vocabulary was evidently prodigious: But how could he be certain that in all the cases where he employed unfamiliar words, he was grammatically and factually right? What prevented him, to nudge him forward by a couple of centuries, from becoming an occasional Mr. Malaprop?

The questions are worth posing simply to illustrate what we would now think of as the profound inconvenience of his not once being able to refer to a dictionary. At the time he was writing there were atlases aplenty, there were prayer books, missals, histories, biographies, romances, and books of science and art. Shakespeare is thought to have drawn many of his classical allusions from a specialized

Thesaurus

that had been compiled by a man named Thomas Cooper—its many errors are replicated far too exactly in the plays for it to be coincidence—and he is thought also to have drawn from Thomas Wilson’s

Arte of Rhetorique

. But that was all; there were no other literary, linguistic, and lexical conveniences available.

In the sixteenth century in England, dictionaries such as we would recognize today simply did not exist. If the language that so inspired Shakespeare had limits, if its words had definable origins, spellings, pronunciations,

meanings

—then no single book existed that established them, defined them, and set them down. It is perhaps difficult to imagine so creative a mind working without a single work of lexicographical reference beside him, other than Mr. Cooper’s crib (which Mrs. Cooper once threw into the fire, prompting the great man to begin all over again) and Mr. Wilson’s little manual, but that was the condition under which his particular genius was compelled to flourish. The English language was spoken and written—but at the time of Shakespeare it was not defined, not

fixed

. It was like the air—it was taken for granted, the medium that enveloped and defined all Britons. But as to exactly what it was, what its components were—who knew?

That is not to say there were no dictionaries at all. There had been a collection of Latin words published as a

Dictionarius

as early as 1225, and a little more than a century later another, also Latin-only, as a helpmeet for students of Saint Jerome’s difficult translation of the Scriptures known as the Vulgate. In 1538 the first of a series of Latin-English dictionaries appeared in London—Thomas Elyot’s alphabetically arranged list, which happened to be the first book to employ the English word

dictionary

in its title. Twenty years later a man named Withals put out

A Shorte Dictionarie for Yonge Beginners

in both languages, but with the words arranged not alphabetically but by subject, such as “the names of Byrdes, Byrdes of the Water, Byrdes about the house, as cockes, hennes, etc., of Bees, Flies, and others.”