The Promised Land: Settling the West 1896-1914 (29 page)

Read The Promised Land: Settling the West 1896-1914 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

When the editorial junkets began to strain the public purse, White traded free trips in return for free advertising. The press swallowed the bait. The Michigan Press Association was so eager that it offered to

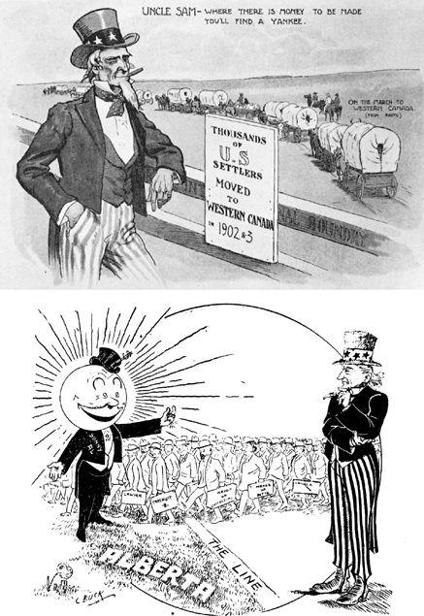

give two or three dollars worth of ads for every dollar Canada expended – and all in advance of each junket. To secure the co-operation of the Western American press, White also dangled the carrot of paid advertising. The placing of the most minuscule ad was enough to soften up most newspapers and put them strongly in the Canadian camp, producing glowing accounts of the Western prairies and attacking those interests who were opposed to American emigration. By 1902, Canada was advertising in seven thousand Western American papers – but only in the slack seasons when the farmers had time to read.

White didn’t have things all his own way. Midwestern leaders were appalled at the exodus to Canada and took desperate steps to counteract it. At the height of the boom it was estimated the Americans were bringing between $50 million and $60 million a year into Canada in cash and equipment. Peter Muirhead of Oklahoma City, to take one example, arrived in Calgary in 1902 with six carloads of animals, two carloads of equipment, and enough ready cash to buy a three-thousand-acre ranch. That constituted an enormous drain on the small American community he had deserted. No wonder, then, that White found himself in a battle with American land companies, business men, politicians, railways, and real estate interests.

In Wisconsin, the anti-Canadian campaign was so virulent that the Canadian agency was driven right out of the state. The Wisconsin Central Railroad bought off the Canadian sub-agents as quickly as they were appointed. Wealthy Wisconsin lumbermen, who owned millions of acres of cleared land in the state, fought so hard against the resident agent, James MacLachlan, that he asked for a transfer. Business and real estate officials pressured county fairs to reject his exhibits, and he was reduced to operating from rented stores near the fairgrounds. White made no headway with the local paper in Wausau, where the Canadian immigration office was located. It refused all Canadian advertising and published features on disgruntled American farmers returning home from Canada disillusioned. White suspected that Wisconsin land promoters had actually sent fake farmers disguised as settlers into Canada with orders to return with stories of personal hardships and broken government promises.

The last straw came in the summer of 1903, when MacLachlan, arriving one morning at his office in Wausau, found a small package tied to the knob of his door. It contained a condom filled with cotton batting and a card attached with this message: “Suck this, it’s good enough for a canuck – why cant [

sic

] you work in your own country?”

That winter, White threw in the towel and transferred his agent to South Dakota.

But White’s most formidable opponent was the powerful railroad magnate James Jerome Hill, whose successful completion of the Great Northern from St. Paul to the Pacific was hailed as the greatest feat of railway building on the continent. Hill’s was the only transcontinental railroad in the United States built without government subsidy and without financial scandal. A garrulous, one-eyed former Canadian, Hill had also been in on the birth of the Canadian Pacific. But now he had no intention of seeing the hard-won profits of his line diminished by a massive loss of customers to Canada. If he could best E.H. Harriman and keep the Burlington line out of Chicago, why couldn’t he just as easily defeat his former countrymen, Sifton and White?

Hill’s headquarters, St. Paul, became a hotbed of anti-Canadianism. The St. Paul

Globe

, which Hill controlled, bristled with features purporting to show that Canadian soil conditions were inferior to those below the border. Every effort was made to snatch prospective emigrants away from the Canadians and redirect them to American homesteads. As a result, White’s men had to keep them under tight scrutiny as soon as they reached Hill’s city. They “should be closely looked after, taken to my office and guarded every moment they spend in this city,” the local agent told Ottawa.

Jim Hill was no stranger to the Canadian North West. His closest friend and former partner was Lord Strathcona, who, as plain Donald Smith, had been Member of Parliament for Selkirk, Manitoba, and who was still a major shareholder in Hill’s railway. But Hill had no compunction about manipulating the facts to his own advantage; he had done it before when, as a consummate lobbyist, palm-greaser, and propagandist, he had turned a bankrupt railway into a thriving success. Now his efforts were channelled into depicting Canada as an arctic nation whose soil was poor and whose grain yield was pathetic. In a remarkable and widely reported speech in Bismarck, N.D., in 1903, the leonine Hill was at his most pugnacious:

“I am not saying much about the area of their land up there, and I am not so much frightened about their climate or the quality of their soil. They are pretty near where Sir John Franklin met his misfortune, that is somewhere near the North Pole. I have seen fields of their wheat … it would not yield a bushel to the acre. It is a handsome growth with nothing in it. I knew these things when I was interested in the Canadian Pacific. Our people who have gone there will, a great many of them, come back.”

Hill’s attempts to depict the Canadian wheat fields as “somewhere near the North Pole” were taken up by friendly American newspapers, one of which went so far as to publish the tale of a Manitoba postmaster pursued by man-hungry wolves to within a mile of Winnipeg and saved only by the fleetness of his team. The story was not short on colourful details: so close was the ravenous pack, the paper announced, that the beasts tore to pieces the buffalo robes hanging over the back of the cutter!

Yet the anti-Canadian campaign failed. Each year, it seemed, the number of Americans flooding into Canada doubled. In both Alberta and Saskatchewan, the American-born soon outnumbered the English by a ratio of two to one. In both provinces they formed the largest single immigrant group, their numbers even exceeding the combined immigration figures from

all

British possessions. Alberta was by far the more Americanized with 80,000 native-born Americans, 67,000 British, and 58,000 Slavs – figures that give a clue to its present-day personality.

In spite of these statistics, Jim Hill didn’t abandon his campaign. As late as 1912 he was still vainly battling away. With his blessing and support the northwestern states held a convention in Seattle designed to organize one last-ditch attempt to stop Americans from moving north. Alas, on the very day the convention opened, the delegates were embarrassed to open their Seattle

Times

and discover a large advertisement from Canada showing a Canadian wheat field with a furrow two miles long. “We ought to be ashamed of ourselves to permit such a thing!” cried the president of the Seattle Commercial Club. The convention came to nothing. Jim Hill had by then won his battle with his crafty rival Harriman. But he had not been able to compete with the attractions offered by the Canadian West or nullify the hard sell of Will J. White.

2

Catching the fever

In the case of the Americans, Clifford Sifton had no need to defend his policies to the Opposition or to the public. Most Canadians, especially Westerners, welcomed American immigration, and with good reason. The Americans were not paupers; on the contrary, they brought money into the country. More, they were practical farmers with years of experience under conditions very similar to those on the northern

plains. They were white, the majority were of Anglo-Saxon extraction, and they all spoke English.

In the eyes of the Westerners, the Americans were everything the English were not. They were go-getters who were willing to work. They did not keep to themselves but mixed easily with their neighbours. They adapted swiftly to Canadian ways. They did not poor-mouth the country but welcomed the Canadian lifestyle with its emphasis on order and security.

Almost every man who crossed the border from Iowa, Nebraska, North Dakota, or Minnesota was a walking success story before he arrived. The Americans had sold their farms for fancy sums, and now they were picking up new land in Canada for a song – 160 acres free, the rest for as little as a dollar an acre. They loved their adopted country, melted easily into the national fabric, and became patriots. More than any other group, they acted as a spark to touch off the prairie land boom.

Small wonder, then, that the press was ecstatic. “Desirable” was the mildest adjective used to describe them. “Absolutely the pick of two continents,” was the headline in the

Winnipeg Tribune

in 1906. The Lethbridge

Herald

went into paroxysms of hyperbole over the American invasion: “This class of immigration is of a top-notch order and every true Canadian should be proud to see it and encourage it. Thus shall our vast tracts of God’s bountifulness … be peopled by an intelligent progressive race of our own kind, who will readily be developed into permanent, patriotic, solid citizens who will adhere to one flag – that protects their homes and their rights – and whose posterity … will become … a part and parcel of and inseparable from our proud standards of Canadianism.”

So let us wait, for a day or two, on the

CPR

platform in Calgary and watch the Americans pour in.

It is March, 1906. The depot’s baggage room, the immigration hall, and the adjacent hotels and restaurants that straggle along the rail line are jammed with newcomers. The wooden platform is crowded with Calgary businessmen, here to welcome “the most extraordinary movement of substantial settlers” ever recorded in the town

.

There are no sheepskin coats here, no babushkas, no riding breeches or Stetsons. These are well-turned-out entrepreneurs in expensive suits, with watch chains draped across their vests. Only their faces, weathered by sun and wind, tell us they do not belong in the cities

.

A fugue of regional accents ripples across the platform: the flat twang of Iowa, the softer sibilance of Missouri. These people have brought their families; they intend to stay. Small boys in caps and knee breeches dash about. John M. Rowan of Randolph, Nebraska, is heading for Olds with eleven children. Marmaduke O’Malley of Pilot Knob, Missouri – a lean Southerner with a drooping moustache and chin whiskers – has four offspring and doesn’t care where he locates as long as the country is as good as advertised. Mary Colwin of Camehester, Oklahoma, a veteran of the Cherokee Strip land rush and a victim of the subsequent drought, has sold out and is starting afresh with her three boys – the eldest barely sixteen – an erect little widow with a face burned brown by the Oklahoma sun

.

The trains steam into the depot, section after section, two hours apart, each section containing seven to eleven cars. Captain Jimmy Winn, the immigration agent, has been up since 2:30 a.m., when the first contingent arrived. They say he is the busiest man in Canada this week. One special arrives with six hundred passengers aboard, all wealthy enough to afford sleeping cars. They have come from Indian Territory, Oklahoma, Kansas, Arkansas, Missouri, travelling north through St. Paul to Winnipeg and then west by the

CPR

. The border crossing is so crowded, they say, that customs agents cannot cope with the crowds, and some settlers have been delayed for days. And this is only the vanguard of the summer rush. As everyone says, the fever is on

.

Here is V.D. Hag of Red Oak, Iowa, who has already scouted the land between Edmonton and Cardston and brought scores of neighbours north in twenty-five cars. They will not bother with free land, all being wealthy enough to buy their farms outright. Hag has a fortune on paper, having already refused one hundred dollars an acre for his property at Red Oak. Iowa, he says, is stirred up about Alberta. “You can hear it talked of everywhere. The rush this summer will be something enormous. I don’t think you Canadians appreciate the interest of Iowa people in Western Canada. It is as contagious as the fever.”

Another Iowan, Charles Cherry, announces that two dozen of his neighbours are on their way from Logan. “We have gone land crazy about Western Canada,” he declares. “Where did I catch the fever? Well now, stranger, that would be hard to say but gosh, I’ve got it all right. For a man of my age – and I just turned fifty-five the day I started for Canada – wouldn’t be tramping around in a foreign country looking for a new home among strange people.”

Sunny Al Welcomes the Horde of Investors and Settlers From the South

But Charles Cherry knows very well how he caught the fever. He caught it because, having learned of free land and cheap land just north of the border, he saw a profit in emigration. No eloquent phrases lured him to Canada. He owned 315 acres of good bottom land in Washington County, has sold 90 acres for $10,000, is hanging onto the rest for the moment and, with the help of the Canadian government’s aggressive immigration agents, has arrived in the promised land

.