The Punishment of Virtue (6 page)

Read The Punishment of Virtue Online

Authors: Sarah Chayes

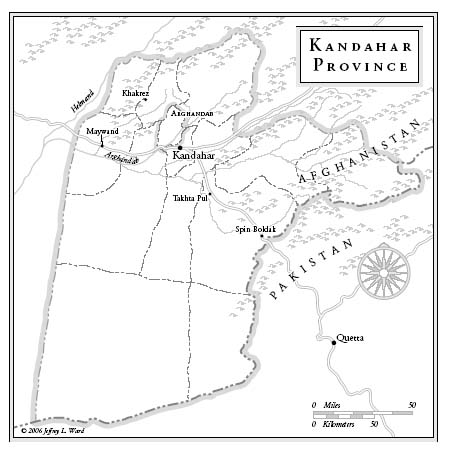

I only wished the debate over Al-Jazeera would draw a clearer distinction between its journalism, which hardly seemed to violate the codes of the profession, at least no more than Fox News did, and actions its management or staff might take to provide concrete assistance to one party to the conflictâsuch as what I witnessed in Spin Boldak.

I later asked my driver: “Did you see that tall black guy working for Al-Jazeera?” He confirmed the Al-Qaeda connection. “He's doing

jihad

,” he said. He had asked a Taliban counterpart about the man, and had been told that this “Al-Jazeera crew member” had called Taliban leader Mullah Muhammad Omar on a satellite phone from outside our compound, and received the order to make us leave.

We were given an hour and a half. I ambled over to the BBC, whose Adam Brookes was becoming a friend, to let him in on what I had learned. I was thunderstruck that he and his crew were even hesitating. When I explained about the Nubian man, they said: “Well that's that, then,” and very efficiently set to breaking down their camp. At CNN, by contrast, the frustration boiled over like lye. The producer got on the satellite phone to Quetta to ask contacts among Pakistani Taliban to intercede with our minders to let us stay. What value any protection might have had if extracted under such duress apparently didn't enter into his calculations.

At length, more or less on schedule, we decamped. I gave my driver my French jackknife, and he tenderly took the compact disk bearing a traveler's prayer that hangs from his rearview mirror between thumb and first finger. “It's like you people cross yourself,” explained my interpreter. I didn't need it spelled out. And we roared out of the gate, in a cacophony of beeping horns. Three truckloads of stick-wielding Taliban preceded us to scatter the crowd. Najibullah, the black-haired, bespectacled security chief we had gotten to know, kept driving up and down the length of the convoy like an anxious herd dog. And he posted himself, radio in hand, at the border crossing to see us through.

The exercise was an empty one, of course. No matter how stiff a front the hard-liners tried to put up, their regime was disintegrating. This was the third week in November, 2001.

THE FALL OF THE TALIBAN

DECEMBER 2001

B

Y EARLY

D

ECEMBER

, the two anti-Taliban proxy forces stood poised on each side of Kandahar. Future President Karzai had set up a base camp in a village about an hour's drive to the north of town, and Shirzai and his patchwork troops were dug in at that strategic pass on the road to the south, ready for the American command to move in on the airport. The Al-Qaeda Arabs had retreated to hardened shelters there, where they were being subjected to an earth-gutting pounding by U.S. bombers.

Under pressure of this persuasive variety, the drawn-out negotiations inside the city of Kandahar were finally bearing fruit.

The man Karzai had chosen to lead these talks was Akrem's tribal elder, Mullah Naqib. That's the Mullah Naqib who posted himself at the left turn in Arghandab waving our funeral cortege on. The same Mullah Naqib who had permitted the Taliban to seize Kandahar in the first place in 1994âover Akrem's furious opposition. How these bewildering reconfigurations came about is part of the underlying pattern of events in Kandahar. Not for months did I begin to perceive it.

Without contest the most celebrated resistance commander locally, credited with driving the Soviets out of the region all the way north to Urozgan Province, the leader of one of the most populous and warlike local tribes, Mullah Naqib is an important power broker in Kandahar. And yet he is a curious rendition of a fearsome Afghan gun lord. He greets you enthusiastically, an irrepressible grin splitting his oval, bushy-bearded face. In a country where shrewd lying is the accepted mode of communication, Mullah Naqib is guileless, if prone to exaggeration. I gave him a small pocketknife once, on my return from a U.S. trip. He treated it like the Hope Diamond, turning it over and over in his hand, showing it off to his son, and proclaiming that if he had been to the United States himself and looked in all the stores, this was the very knife he would have chosen. Even in the thick of bitter factional fighting in 1992, when a rival group rocketed one of his trucks and killed all thirteen fighters inside, Mullah Naqib refused to seek retribution. He was just back from a pilgrimage to Mecca. “I can't be killing Muslims now,” he told his angry men.

To put together my puzzle of those late November days of 2001, the final spasms of the Taliban regime, I needed Mullah Naqib's account too. And he, a year and a half later, was happy to oblige.

“Three days after President Karzai went inside,” he told me, “he sent me a satellite phone.” By then Mullah Naqib had withdrawn from Kandahar proper to his tribe's heartland just to the north. Leafy Arghandab is blessed with a river. Tangled orchards, like unkempt forests inside their earthen walls, could hardly offer more of a contrast with dun-colored Kandahar. When the farmers flood their land to let the trees drink, you have to pick your way through the groves on small raised paths, or sink ankle deep into the muck. Mullah Naqib was living in the fort he built to direct the anti-Soviet resistance.

“The Karzais' man brought a satellite phone to me in Arghandab,” he remembers. “He said Mr. Karzai wanted to talk to me. So we called the president, and he asked me: âWhat do you need? Money? Guns?' I told him, âBoth!'”

From then on, the two friends talked every day. “I was giving Karzai advice on tactics,” Mullah Naqib grins. “I'd say, âDo this, now do that' because he doesn't know anything about fighting. And he told me to try to separate the Taliban from Mullah Omar.”

And so began the delicate task of prying the Taliban subcommandersânever quite subordinate, always semi-independentâaway from their failing leadership. It is the time-honored ritual, another form of customary dispute resolution. It is the process of talking people out of conflict before it ever erupts.

Once, the Taliban defense minister sent a car for Mullah Naqib. The men met secretly in downtown Kandahar. “Don't fight against Hamid,” Mullah Naqib told the minister. “He won't do anything bad to you if you surrender.” Not two months after the 9/11 disaster, indeed, there was talk about a “broad-based coalition government for Afghanistan,” which might include top Taliban leadership.

1

By late November, Mullah Naqib's Alokozai tribesmen were itching to attack the spasmodically kicking, but clearly drowning, Taliban. Mullah Naqib sent an envoy to Taliban leader Mullah Omar with a letter: “Surrender by the day after tomorrow, or all Arghandab will take up arms against you.” This was a potent threat, since Mullah Naqib's Alokozais had never been beaten in a fight. It is accepted truth in Kandahar that the only reason the Taliban were ever able to capture the city in 1994 is because, after those heated arguments with Akrem and like-minded commanders, Mullah Naqib ordered his Alokozais to let them do it.

Mullah Naqib's ultimatum prompted another meeting in Kandahar, on December 5, 2001. The Taliban officials threatened to go ahead and fight if Mullah Naqib did not agree to their terms for the surrender. “You want to make war on us?” the tribal chief says he challenged. “You want to destroy our homes? Why didn't you fight in Mazar-i-Sherif, or in Kabul, or in Qunduz?” The Taliban had precipitously abandoned those faraway cities to the Americans' proxies from the Northern Alliance weeks before. In reply, the Taliban negotiators demanded to speak directly to Hamid Karzai.

“I'm like this with Hamid Karzai!” Mullah Naqib held up his two twined fingers. “My words are his, his words are mine.”

Karzai, just named interim president of the country, was spading his way through a blizzard of tasks: planning the tactics of the final move on Kandahar with his U.S. advisers, receiving local elders, considering the names of potential cabinet ministers, conducting key discussions with the Taliban leadership, sometimes talking on the phone to Mullah Muhammad Omar himself. The group in Mullah Naqib's house was insisting on a face-to-face meeting at Karzai's village headquarters a half hour north of town. Mullah Naqib remembers their asking for his satellite phone to try to raise the interim president. But the line kept breaking off and they could not get through.

With good reason. Just hours before, an errant U.S. bomb had almost killed the new president. Three U.S. Special Forces officers were dead in the accident, and twenty Afghans. These were Karzai's faithful tribesmen who, with that unique blend of unshakable devotion leavened by an irreverent egalitarianism, would have served him down to the bones of their bodies, and did, many of them. One, named Qasim, took days expiring. Both of his arms were torn off, and he begged his friends to finish him off. Finally, he died in the care of U.S. doctors at the desert marine base where they had medevaced him. Needless to say, Karzai's camp was in an uproar when the Taliban leadership was dialing the number.

Still, the delegation, led by Mullah Naqib, made the trip there across the bald, rock-strewn landscape. At the time, from conversations in Quetta, I was under the impression that the bombing raid was aimed at this very group of ranking Taliban. I was infuriated that U.S. trigger-happiness could have shattered the prospect for a negotiated settlement.

Mullah Naqib may be overstating his role in these eleventh-hour parlays, but he maintains that Karzai, face bandaged where shrapnel had nicked him, did not want to speak with the emissaries, that he, Mullah Naqib, was the one who talked the interim Afghan president into it. “You have to reason with them,” Mullah Naqib admonished. “Because if we fight, there will be blood in the streets of Kandahar, and we will look bad.” Karzai sat down with the Taliban officials, and instructed them to turn over the city to Mullah Naqib.

“But when they got back to Kandahar,” Mullah Naqib pursues, “they changed their minds. They said they wanted to see the president again the next day.”

Again the delegation traveled to the camp. Again the Taliban officials met with Karzai. Again they agreed to surrender Kandahar. They set the deadline for two days later. But once more, their word did not withstand the trip back to townâwith significant repercussions for an orderly transfer of power.

“When we reached Kandahar,” recounts Mullah Naqib, “the Taliban declared they were not going to wait two days to pull out, they were going to leave tomorrow. Then, that very same night, they called me on the satellite phone and announced: âOur people are going.' I wasn't ready. I didn't have enough men. I spread the forty or fifty fighters I had around town.”

It wasn't enough. As the Taliban fled that nearly moonless night, Kandahar slid into precisely the kind of pandemonium that Afghan refugees in Pakistan had been nervously predicting to me for days. This was the one thing they feared, they kept saying, when they contemplated an end to the Taliban regime: a return to chaos.

A doctor at the main city hospital lived through a Dantean scene that night. Several hundred wounded Arabs and some Taliban had flooded the leprous hospital groundsâsurvivors, no doubt, of U.S. bombing at the airport. They were outside, lying scattered about on the ground. “When they brought them here, we were doing triage,” the doctor told me a week later. “It was the last night, when the situation was very badâthe night the Taliban were leaving and they were surrendering power to Mullah Naqib.” The doctors worked furiously to sort and stabilize the patients in the cold and the encroaching dark.

As abruptly as they had first come to drop off the wounded, a fleet of Al-Qaeda pickup trucks roared back to the hospital, and Arabs, shouting at the doctors to stand clear, began pulling the patients from their hands and loading them, with their half-applied bandages and IV tubes, back into the trucks for the headlong flight from Kandahar. “Immediately cars came and took them all, with the Taliban. The cars belonged to the Arabs,” said the doctor.

Just fourteen badly wounded men, including one Australian, were left behind in the hospital, where they were the target of at least two U.S.-led raids, which degenerated into gun battles right on the hospital grounds.

Niyamatullah is the son of a Kandahari almond merchant. He was working with his father at the wholesale almond and dry fruit market those days. Great mounds of almonds of different classes and qualities lie on tarps in the courtyard, men wading in them shin deep, or else weighing them out in sacks on brass balances. Surrounding the courtyard on three sides is a columned arcade, just a shade darker than the almond shells, housing shops and storage cellars for the different merchants.

“Right next to our market is a big mechanics' yard,” says Niyamatullah. Such auto repair yards are grease-smudged obstacle courses, hidden from the street by the buildings that enclose them, with different mechanics working out of the back of cargo containers, bits and pieces of cars studding the trampled, oil-soaked ground. “There were lots of Taliban vehicles that had been left there for repairing. Suddenly gunmen appeared and snatched all the cars, then another group came and took them away, then the first ones came back. And they fought over the cars. I thought we were back to the civil war before the Taliban time.” Like Wall Street after 9/11, the almond bazaar closed its doors and battened down its hatches for three full days.

The free-for-all that engulfed Kandahar was a repeat of the scene in Kabul three weeks earlier. America's proxies from the Northern Alliance had ridden rambunctiously into the Afghan capital, after U.S. bombing had emptied it of Taliban. Chaos reigned for days. The same thing would happen a year later, when U.S. soldiers conquered Baghdad in Iraq, and then proved utterly unequipped to deal with the human hurricane that shrieked into the vacuum they had created. It seems that planners underestimate the centrifugal forces that can be unleashed when a regimeâno matter how unpopularâis toppled.

Even so, the transfer of power in Kandahar might have gone differently. Had Zabit Akrem been there, with his instinct for order and his ability to command, he might have been able to rein in the boisterous fighters and save the city two days of looting. But Akrem was still outside town, with Gul Agha Shirzai at the airport. In fact, Akrem was standing next to the former governor when a call came in over the satellite phone.

“President Karzai called Gul Agha. I was there. Mr. Karzai said, âYou will be the commander of the airbase, and Mullah Naqib will be governor.'”

Botched though the transition in Kandahar may have been, Akrem was saying, the intended division of power was clear. All the eyewitnesses concur with him: President Karzai designated Mullah Naqib to accept the Taliban surrender and take command of the city.

A young fighter from Chaman told me so a day or two after the fact. “The Taliban handed over power to Mullah Naqib,” he said. Niyamatullah the almond seller remembers that “all the Taliban were going to see Mullah Naqib and giving him their weapons.” My Achekzai friend Mahmad Anwar confirms: “It was the Alokozais who cleaned the Taliban out of Kandahar. Mr. Karzai gave Kandahar to Mullah Naqib.” Mullah Naqib himself refers to outside authority for proof: “The BBC broadcast that I was to accept the Taliban surrender and take over the province.”

That is how it was supposed to be. But that is not what happened.