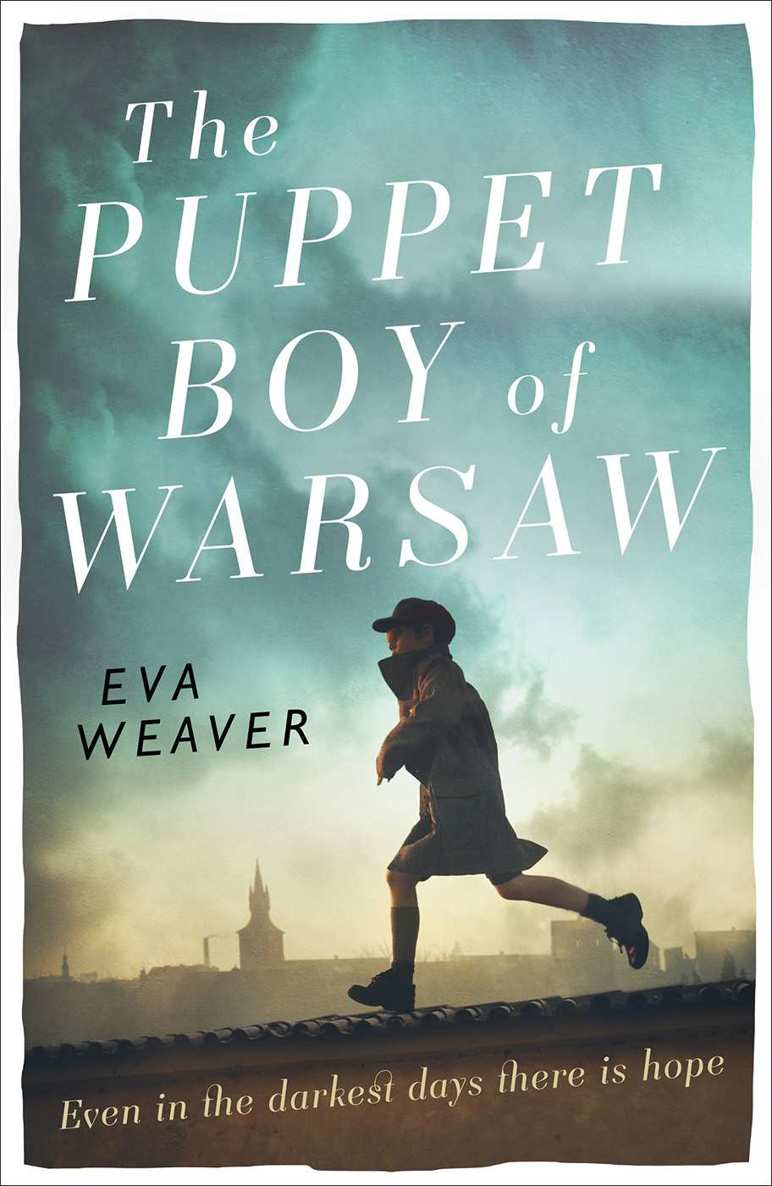

The Puppet Boy of Warsaw

Read The Puppet Boy of Warsaw Online

Authors: Eva Weaver

For the victims of war then and now

May this book support dialogue, healing and peace

PUPPET

BOY OF

WARSAW

Eva Weaver

Part Two: The Prince’s Journey

W

ithout the coat nothing would have happened as it did. At first it was only a witness, a black woollen coat with a six-button row, but becoming a pocket-coat made it an accomplice.

Now it lies gutted, like a boar of its entrails, emptied out to the very last item. Battered and out of fashion, everything it once sheltered has gone: Mika and his puppets, the old gold-rimmed spectacles, the beggar’s flute, the faded letters, the photographs, and, of course, the children. All but the last book Mika slipped into one of its pockets like a secret. Bound in dark red leather, no bigger than a notebook, filled with photographs, cut-outs and scribblings, Mika’s ‘Book of Heroes’ is a sunken treasure hidden in the coat’s seams.

When Mika bundled up the coat and stuffed it in a box he was still a young man. Mika’s last night as a bachelor was the coat’s dark night of the soul. Here, untouched by sunlight, the coat slipped into oblivion, slowly forgotten by all those who had once held it dear: Nathan the tailor, Grandfather Jacob, Mika, Ellie, the mothers, the twins, the puppets, and the orphans . . .

Then, Mika returned. No warning, only a flash, then light like heaven. There he stood, grey as his grandfather, old as good wine, and next to him, with brown chocolate eyes, a boy the size and build of Mika at the time when the coat first became his.

Measured by the old tailor’s knowing hands, cut, stitched and adorned with a row of fine black buttons, this was no ordinary coat. And when the Germans took Warsaw and Grandfather Jacob transformed the coat into a pocket-coat two years later, it found a purpose.

But before the pockets, the armband arrived: a blue Star of David worked on a piece of white cotton, stitched tightly on to the coat’s right sleeve like a mark. Look closely and you can still see a dark blue thread where the armband was fixed, an innocent piece of yarn from Mother’s needle basket.

Over the years many things have mingled in the coat’s pockets and become entangled, but the girl, she changed everything. For her, the coat became a vessel, Jonah’s whale, swallowing her whole so she could be delivered safely to the other side.

She was the first child to be smuggled and she smelled of sleep, deep, oblivious slumber and strong, cheap soap. The matron must have scrubbed her from head to toe. At least she would smell nice if captured. Perhaps the fresh, soapy smell would protect her, cast some doubt in a soldier’s mind. A cherished memory of his own child, clean, ready for bed . . .

That first night the coat sheltered the oblivious girl, folded itself around her as tightly as possible, her curls rubbing against its silky insides like coarse wool. And then she was gone, handed over in a flash, only her smell still lingering for a while like an afterthought . . .

1

New York City, 12 January 2009

A

fter a blizzard, snow glistened under a brilliantly blue sky. New York was magical in the first snow, muted and utterly transformed. Despite the snow, or rather because of it, Mika insisted on walking the few blocks from the subway to the museum.

Snow takes the edge off everything. Like a disappearing act.

Even after a sleepless night and with pain nagging his left knee the old man hummed: the fresh snow held promise and Sunday with his grandson brought a welcome change to his insular existence. Daniel had arrived early to make the most of the short winter’s day and after an ample breakfast Mika had suggested they mingle with the dinosaurs at the Natural History Museum. So wrapped in thick scarves and hats to shield them from the cutting wind, they took the subway exit on 72nd Street and headed north towards Central Park.

Daniel was tall for his thirteen years, lanky and agile with delicate features that radiated curiosity and a pinch of cheekiness. Mika had always been fond of his grandson’s unashamed laughter and his black unruly curls. Like Hannah. So like Ruth. Every so often the pair broke into a foolish little dance, kicking the powdery snow into caster-sugar clouds, Daniel with his shoes, Mika swinging his stick. They giggled with delight.

It happened as they walked down 72nd Street towards Columbus. They passed a small theatre – from the outside not much more than a large, shabby red door with a printed sign. Mika noticed out of the corner of his eye a colourful poster, proclaiming in bold letters: ‘

The Puppet Boy of Warsaw – a Puppet Play

’.

Mika slowed down but didn’t stop, despite the cold sweat gathering on his forehead and between his shoulder blades.

The poster’s words were printed over a picture of an old black coat lying spread out as if it were about to dance or fly away, a Star of David armband stitched on to the right sleeve. A blue star, he noticed, a Polish one, not yellow like the ones the Jews were forced to wear in other places. And there were puppets, lots of different puppets, sticking their brightly coloured heads out of the coat’s many pockets: a crocodile, a fool, a princess, a monkey.

Mika’s heart pounded, quick, deep beats like those of a crazy drum. He reached inside his coat, first the left, then the right pocket, fumbling, searching for something. Nothing there but an old crumpled handkerchief, a pencil stub, another pair of gloves. Suddenly vertigo and a strong wave of nausea washed over him and with it a sense of helplessness and rage he feared would devour him like a lion gorging on his insides. His chest tightened and he gasped for air. As he clasped Daniel’s arm, his voice sounded thin and strained.

‘Danny, please, let’s go home. I need to show you something.’

‘What is it? Are you OK?’

‘Yes, I just need to go back. I’m sorry, Danny.’ Mika swayed, clutching his stick, but the images were already flooding in: a small figure, stumbling over an endless field of smouldering rubble; a huge black shape above him flapping like a massive crow; a coat, inhabited by a screaming troupe of puppets, chasing after him, trying to catch him once and for all.

As he leaned against the wall the images began to fade but his knees buckled and he felt himself sliding to the ground, a deep ringing in his ears and then blackness.

He didn’t know how much time had passed, but then he felt Danny’s hand, patting his cheek.

‘Wake up, Grandpa.’

A figure from across the street called out. He couldn’t hear what the man was saying

. He shouldn’t be on the sidewalk if he’s a Jew like me. Hasn’t he heard? It’s forbidden to walk on the sidewalk. Or maybe he’s German?

The stranger crossed the road.

‘Here, Pops, take a swig, that might help.’ Danny pressed a small silver flask to his mouth. It stuck to his lips.

‘Everything OK?’ The man from across the road bent over him, friendly, concerned, his forehead all furrows. He wasn’t wearing a uniform after all, but a woolly hat and scarf.

Still, never trust a stranger’s smile. Must get up. Can’t die here.

Danny held the flask to his lips again. Mika took a large swig then coughed.

‘You want to kill me? What’s that?’

The man laughed.

‘Stroh rum, seventy-five per cent Austrian. Perfect for emergencies. Can even bring back the dead sometimes. You’re feeling better?’

‘Thanks, yes.’ Mika shook himself like a dog coming out of water.

‘Can you get up?’ Danny was right by his side. ‘I could call an ambulance.’

‘No, I’m fine. Really. Just help me up.’

Daniel and the man grabbed one arm each and lifted him up. Mika’s legs felt alien, and somehow far away, as if he were looking through binoculars the wrong way. He stomped his feet a few times on the icy ground.

‘That’s better, thank you. I need to go home.’ His head hurt.

‘You’re sure you can walk, Pops? Get a cab at least?’

Mika smiled. They had not seen a single car since they stepped out of the subway. Carlessness was part of the magic of the first snowfall.

‘No, let’s just go. And thank you, sir, for the rum – that should do the trick!’

Danny handed him his stick. They didn’t speak but Daniel linked his arm through Mika’s, supporting him as they made their way through the snowy cityscape. Mika allowed him, and more than that, he was grateful.

They took the subway and after another short walk they finally reached Mika’s apartment block. The elevator took them to the fifth floor. After opening the door Mika quickly unwrapped his coat and scarf and became animated.

‘Danny, please go to the wardrobe in the bedroom and bring me that big brown parcel behind the clothes.’

The box had been sitting there for many years. Mika had carefully sealed it up the day before he asked his wife to marry him. He was twenty-eight then and had only opened it once since then, last October, when he had added one last item.

Daniel reached far into the wardrobe and pulled out the package. For a moment he swayed under its weight.

‘Have you got bricks in there?’

‘No, just bring it over here.’ Mika’s hands trembled as Daniel carefully placed the box in front of him. His fingers slid over the crumpled brown paper, tenderly exploring every side. Then, with a sudden jolt, he sliced through the cord with a sharp kitchen knife. No need to carefully untie the parcel now – he would never do it up again. He grabbed the box and slowly lifted the lid. The smell was overwhelming, sharp and pungent.

‘What is it, Grandpa?’

‘I want to tell you about what happened in the ghetto. I want to tell you before I die. I want to tell the truth – to you and to my own heart, to your mother and maybe the world.’ With both hands he pulled out a huge coat. Heavy and black. It reminded him of the large black dog he had found the previous week, lying dead at the entrance to Madison Park as if struck down by lightning. But his old coat had life in it still.