The Puzzle of Left-Handedness (4 page)

Both stories suggest at the very least a pragmatism that many left-handers will recognize from their own experience. The overwhelming majority of their fellow human beings regard the left hand as the bad hand, but sometimes left-handed people can be useful, and why wouldn’t you want to make use of them? It seems the negative associations surrounding the left are not insurmountable, even in biblical mythology. This raises the question of how strong the connection between the left and evil in our symbolic thought patterns really is, and whether perhaps there are other connections that make for rather more subtle attitudes towards the left.

6

Magic and Superstition

What are the norms, values and value judgements by which people are guided in daily life, in ‘thinking without thinking’? They emerge vividly from superstition, which is closely bound up with our deepest being and survives in the face of any amount of oppression. Early church patriarch St Augustine fulminated against it, as has virtually every authority since, but that hasn’t helped. Even people with apparently modern, businesslike, rational attitudes can be found driving around with horseshoes bolted to their radiator grilles or trying to avoid walking under ladders. More importantly still, superstition is informal. It arises spontaneously, rather than being devised and prescribed, and nothing is carved in stone; there exist no authorized versions. It therefore gives us a fairly accurate impression of the things we truly associate, deep down, with left and right. At least, it does so a good deal more directly than the simplified and to some extent artificial systems of etiquette, philosophy and established religion that are based on it, such as Pythagoras’ Table of Opposites.

Even just within Europe, superstitions that refer to the left side, the right side and the left hand are plentiful. Many have to do with witchcraft and duplicity. To start with the latter, there are many traditional ways of committing perjury with impunity. In some places it’s enough to keep your left hand in your pocket while taking the oath, or to touch your jacket button with it as you give your word of honour. We can guard against this particular form of duplicity by making it compulsory to raise the left hand while swearing to tell the truth and nothing but the truth, but in a number of cultures this in itself is reason enough to regard an oath as non-binding – in America, for example, as viewers of its countless courtroom dramas will know.

From present-day Belarus and surrounding regions comes a belief in the

hecktaler

, a coin that always returns to its owner as long as he pays it out with his left hand while gently treading on the seller’s left foot. This sounds ideal for anyone hoping to make a quick buck, but how do you come by such a coin?

Hecktalers

were originally owned exclusively by people who had sold their souls to the Devil, or by Jews – it seems people in Belarus made no firm distinction between the two. Others could make a

hecktaler

their own by treating a buyer who offered to pay with one in a similar manner, in other words by accepting the coin with the left hand and surreptitiously treading on the buyer’s left foot.

Anyone unable to lay his hands on a

hecktaler

could always get rich by gambling, since good luck could be guaranteed by the following elaborate, if unsavoury, procedure. The day before a gambler has a chance of winning the jackpot, he catches a toad. That evening he pushes a needle and thread in through one eye of the toad and out through the other, right through its head. The story doesn’t mention whether the poor creature has to be alive. Then the toad is tied to the fingers of the left hand by the thread, where it stays until the following morning. The gambler is certain to have luck on his side.

The left–right distinction is often a key element in procedures for overcoming a fear of supernatural figures such as witches, dwarves and vampires. For example, both right and left are of crucial importance in a centuries-old remedy for young parents fearful of evil dwarves intent on replacing their child with a changeling. lay a right shirt sleeve and a left sock in the cot next to your child and it won’t be stolen. You’ll just have to hope it doesn’t suffocate amid all those bits of fabric. From time immemorial, bakers in the German region of Swabia have pressed the fingertips of their left hands into the dough of the last loaf to go into the oven to prevent witches from gaining power over the bread. And did you know that a vampire in its coffin can be recognized not only by the fact that the body does not decompose, retaining a healthy complexion, but because the left eye always remains open? Now that we’re in Romania, the land of Dracula: if a person in that part of the world bleeds from the left nostril, then someone in his or her family has just died. Another bad omen is the barking and wailing of dogs, a harbinger of fire, death and war. Calamities that announce themselves in this way can be averted, it is said, by holding out to the canine in question, with the left hand, the heart of a black dog with a dog’s tooth stuck through it.

All this brings us to another connection, this time between the left hand and the act of killing. If, for example, a witch has turned herself into a toad, then she can be killed only with an axe held in the left hand. Ridding yourself of disagreeable acquaintances is rather more difficult, but here is a somewhat impractical tip from Central Europe: furtively acquire some blood from your prospective victim and wipe it over the sole of the left foot of a fresh corpse just before burial. Your acquaintance will gradually waste away and die.

Then there is love, of course, which prompts the strangest antics of all. In the region of Landshut in Germany, people once believed that a young man out courting could win the love of a girl by secretly stealing a blouse she had worn while cleaning the house, then urinating through the right sleeve. If she later proved a disappointment, the flames of passion could be extinguished by using the left sleeve as a urinal. Fairly revolting, but as nothing compared to the courting advice offered by people in the region around Breslau and Wroclaw. The admirer of a girl he wishes to marry must start by swallowing a whole nutmeg, which is indigestible and will emerge after a day or two in practically the same condition as it went down. It must be fished out of the ordure and rinsed clean. The next Friday the aspiring young man needs to clamp it in his left armpit for an hour ‘in Hora Veneris’, or ‘at the hour of Venus’, in other words at sunrise. The nutmeg is then grated and the lady in question invited for a meal. He must take the opportunity to feed the entire nutmeg to her, after which she will be putty in his hands. Some say it works with cattle too, although one wonders what anyone would want with a hopelessly lovesick cow.

Central Europe is not the only region where the left side of the body is of relevance to supernatural means of facilitating courtship. A third-century Egyptian papyrus describing magical rites includes a recipe for a love potion in which the essential ingredient is blood from the left ring finger.

Many of these stories have unpleasant aspects, usually a cunning deception or the temptation of innocents, but some of the superstitions surrounding the left side and the left hand seem unrelated to either good or evil. The widespread idea that small children who have never looked in a mirror can see themselves reflected in their left hands is simply enchanting. What should we make of the trick that Swiss milkmaids believed would make a recalcitrant cow stand up to be milked: you only needed to wind your left garter around the animal’s right horn. The left hand, perhaps surprisingly, is capable of driving out evil, and not only in the form of a Swabian witch or an enchanted toad. Wiping the left hand over the bedclothes will prevent nightmares, for example. We find something similar in the Punjab in northern India, where a young man will wind an old rag around his left arm to ward off the evil eye.

Finally, here is a truly bizarre belief in which the left can be both good and bad. Not so very long ago in Western Europe, the drawing of lots determined who would be drafted into the army. If you were rich you could simply hire a replacement to endure the barbaric living conditions in the barracks on your behalf, but for men of few means the lottery was a true sword of Damocles. The drop in a family’s income entailed by having to manage without a son who had just reached adulthood might be a devastating blow. For such people the only imaginable solution lay in magic and superstition. It was believed that a young man could rely on meeting with a favourable result as long as he did everything with his left hand for three days before lots were drawn, including crossing himself, assuming he was a Catholic. He also had to make sure he drew his straw with the left hand. Whether this particular left-handed scheme is good or evil depends on your point of view. A militant patriot with plenty of money will regard it as a cowardly means of avoiding an honourable duty, whereas an impoverished wretch is more likely to see it as a god-given opportunity to protect his family from hunger and want.

One thing will by now have begun to emerge from this array of stor ies: the left side of the body has magical, enchanting properties that can be used to do good as well as harm. The following nuggets of wisdom show that the magic involved is usually of a highly specific kind.

How can a persistent fever be treated? Here’s a method cheaper than a visit to a doctor: the sufferer winds a piece of blue wool around a toe on his left foot and leaves it there for nine days. On the tenth day, before sunrise and without saying anything, he goes to an elderberry bush, takes the wool from his foot and winds it around a branch. The fever lifts. Similar methods were used to treat innumerable other ailments. The length of time the wool has to be left in place, the precise body part, and the kind of bush or tree that would absorb the sickness all vary, but a left finger, arm, leg or toe was always involved. A bad coughing fit in the Tirol? let your left arm hang loose. Persistent nose-bleed? A thread wound tightly around the little finger of the left hand does wonders. Infants could be protected from gout by three drops of blood from the left ear of a black sheep. Sick pigs are curable too, the ancient Romans believed: before sunrise, dig up the roots of a hellebore with your left hand, drill holes in the sick animals’ ears and push the roots through. The creatures will revive even as you watch.

Conkers relieve all kinds of complaints, from toothache to rheumatism, as long as you keep them in your left trouser pocket – although there are some regions where people believe they should be put in the right pocket. Medicinal or magical plants can be picked at many different times – just before sunrise or perhaps at midnight, during the new or the full moon – but dozens of cures and spells agree that it must be done with the left hand, preferably with the thumb and ring finger.

All this suggests that the magic of the left hand is the magic of life and death, of sickness and health, including the healthy sickness we call love. This is the most important theme, one that recurs over and over again – far more so than trickery and deceit. Even official Catholic symbolism, which generally doesn’t seem to regard anything about the left side and the left hand in a positive light, has at least one incontrovertible rule that confirms the left’s connection with health, love and vitality. It concerns the marriage ceremony, in which the bride and bridegroom place rings on the ring fingers of each other’s left hands. This custom is derived directly from an ancient Roman engagement ritual,

*

a contract sealed with a ring on the left ring finger, the

digitis medicinalis

, which was seen as having a powerful influence on health. The ring afforded protection, and preserved love. Isidore of Seville wrote that people of his time believed an artery ran from the left ring finger straight to the heart. Perhaps that’s why the blood of this particular finger was required for the libido-boosting drink described on that Egyptian conjuring papyrus.

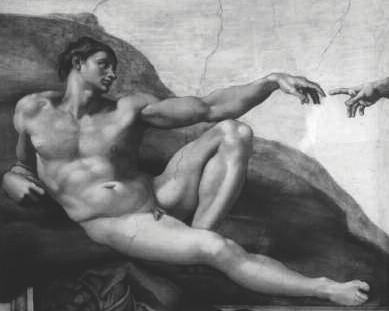

Another indication that European Christian civilization is thoroughly permeated by a belief in the connection between the left hand and health and vitality can be found on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome, in the famous scene where God gives life to Adam. Naturally he does so with his right hand, but Adam, created a moment earlier in the image of God, accepts life with his left. This is remarkable, since left-handedness was generally seen as a characteristic of the Devil. An often heard explanation is that Michelangelo positioned Adam as he did be cause any other arrangement would have messed up the composition. That seems highly improbable. A pope who hires the best painter in the world to create a work of art at such a holy place wants his money’s worth. He surely can’t be palmed off with talk of the job being too difficult – and Julius

II

was hardly the easiest of popes.

There’s a quite different, well-documented, and for the church identifiable and acceptable reason for Adam’s left-handedness: the left hand represents life itself. We see this reflected in another panel of the same section of the ceiling, where Adam and Eve are thrown out of paradise. The fateful deed is depicted on the left: the eating of the forbidden fruit. On the right the consequences are shown. Two pitiful, remorseful and utterly despairing figures flee the implacable Angel of Death who floats above them. This angel is left-handed – and not, of course, because he’s meant to be a henchman of the devil, since he’s acting on God’s orders. No, his left-handedness indicates that this is a matter of life and death.

Adam receives life through his left index finger. Michelangelo, Sistine Chapel, Rome.