The Queen's Vow: A Novel of Isabella of Castile

Read The Queen's Vow: A Novel of Isabella of Castile Online

Authors: C. W. Gortner

Tags: #Isabella, #Historical, #Biographical, #Biographical Fiction, #Fiction, #Literary, #Spain - History - Ferdinand and Isabella; 1479-1516, #Historical Fiction, #General

The Queen’s Vow

is a work of historical fiction. Apart from the well-known actual people, events, and locales that figure in the narrative, all names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2012 by C.W. Gortner

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

B

ALLANTINE

and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gortner, C. W.

The queen’s vow: a novel of Isabella of Castile / C. W. Gortner.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-345-52398-3

1. Isabella I, Queen of Spain, 1451–1504—Fiction. 2. Spain—History—Ferdinand and Isabella, 1479–1516—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3607.O78Q84 2012

813′.6—dc23 2012008559

Title-page and part-title images: ©

iStockphoto.com

/ © jpa1999 (border);

© Evgeniy Dzhulay (crown)

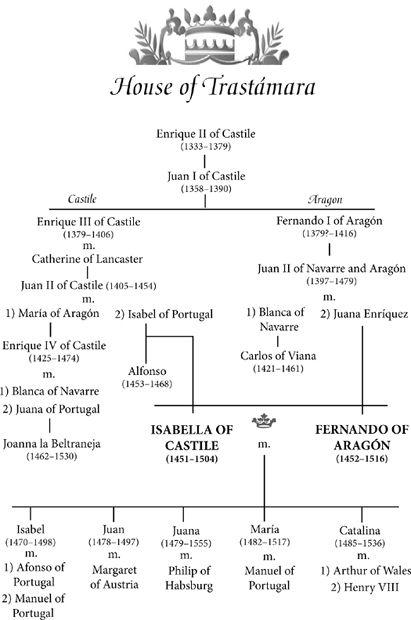

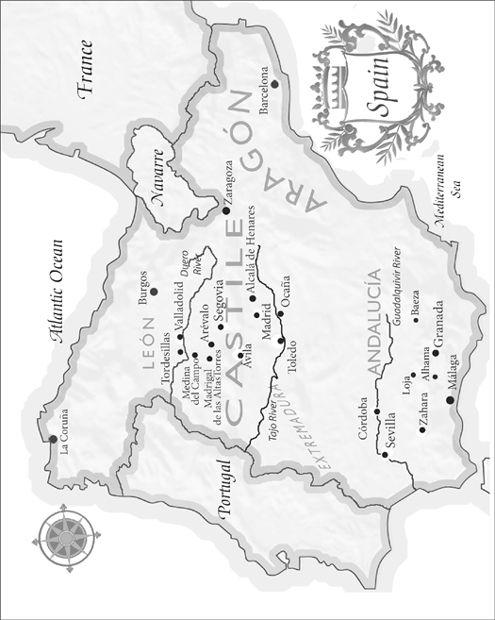

Family tree and map by C. W. Gortner

Jacket design: Victoria Allen

Jacket photograph: Jeff Cottenden

v3.1

I have come to this land and I certainly do not intend

to leave it to flee or shirk my work;

nor shall I give such glory to my enemies

or such pain to my subjects

.

—

ISABELLA I OF CASTILE

PROLOGUE

1454

N

o one believed I was destined for greatness.

I came into the world in the Castilian township of Madrigal de las Altas Torres, the first child of my father, Juan II’s marriage to his second wife, Isabel of Portugal, after whom I was named—an infanta, healthy and unusually quiet, whose arrival was heralded by bells and perfunctory congratulations but no fanfare. My father had already sired an heir by his first marriage, my half brother, Enrique; and when my mother bore my brother, Alfonso, two years after me, shoring up the male Trastámara bloodline, everyone believed I’d be relegated to the cloister and distaff, an advantageous marriage pawn for Castile.

As often happens, God had other plans.

I CAN STILL

recall the hour when everything changed.

I was not yet four years old. My father had been ill for weeks with a terrible fever, shut behind the closed doors of his apartments in the alcazar of Valladolid. I did not know him well, this forty-nine-year-old king whom his subjects had dubbed El Inútil, the Useless, for the manner in which he’d ruled. To this day, all I remember is a tall, lean man with sad eyes and a watery smile, who once summoned me to his private rooms and gave me a jeweled comb, enameled in the Moorish style. A short, swarthy lord stood behind my father’s throne the entire time I was there, his stubby-fingered hand resting possessively on its back as he watched me with keen eyes.

A few months after that meeting, I overheard women in my mother’s household whisper that the short lord had been beheaded and that his death had plunged my father into inconsolable grief.

“Lo mató esa loba portuguesa,”

the women said. “The Portuguese she-wolf had Constable Luna killed because he was the king’s favorite.”

Then one of them hissed, “Hush! The child, she’s listening!” They froze in unison, like figures woven in a tapestry, seeing me seated in the alcove right next to them, all eyes and ears.

Only days after overhearing the ladies, I was hastily awakened, swathed in a cloak, and trotted through the alcazar’s corridors to the royal apartments, only this time I was led into a stifling chamber where braziers burned and the muffled psalms of kneeling monks drifted through the room beneath a wreath of incense smoke. Copper lamps dangled overhead on gilt chains, the oily glow wavering across grim-faced grandees in somber finery.

On the large bed before me, the curtains were drawn back.

I paused on the threshold, instinctively looking about for the short lord, though I knew he was dead. Then I espied my father’s favorite peregrine perched in the alcove, chained to its silver post. Its enlarged pupils swiveled to me, opaque and flame-lit.

I went still. I sensed something awful that I did not want to see.

“My child, go,” my

aya

, Doña Clara, urged. “His Majesty your father is asking for you.”

I refused to move, turning to cling to her skirts, hiding my face in their dusty folds. I heard heavy footsteps come up behind me; a deep voice said, “Is this our little Infanta Isabella? Come, let me see you, child.”

Something in that voice tugged at me, making me look up.

A man loomed over me, large and barrel-chested, dressed in the dark garb of a grandee. His goateed face was plump, his light brown eyes piercing. He was not handsome; he looked like a pampered palace cat, but the slight tilt to his rosy mouth entranced me, for it seemed he smiled only for me, with a single-minded attentiveness that made me feel I was the only person he cared to see.

He held out a surprisingly delicate hand for a man of his size. “I am Archbishop Carrillo of Toledo,” he said. “Come with me, Your Highness. There is nothing to fear.”

I tentatively took his hand; his fingers were strong and warm. I felt safe as his hand closed over mine and he led me past the monks and dark-clad courtiers, their anonymous eyes seeming to glint with dispassionate interest like those of the falcon in the alcove.

The archbishop hoisted me onto a footstool by the bed, so I could stand near my father. I heard the king’s breath making a noisy rasp in his lungs; his skin was pasted on his bones, already a strange waxen hue. His eyes were closed, his thin-fingered hands crossed over his chest as if he were an effigy on one of the elaborate tombs that littered our cathedrals.