The Rape of Europa (42 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

The American Defense Harvard Group was not the only one working on such data. Since January 1943 a specially appointed committee of the American Council of Learned Societies, also convinced of the necessity for art protection, had been organizing itself in New York. In the following months New York responded magnificently. Office space was allotted at the Met. The Rockefeller Foundation gave a $16,500 grant to pay staff both in New York and at Dumbarton Oaks and the National Gallery in Washington. Miss Helen Frick turned over the full facilities of her Art Reference Library to the effort. The American Society of International Lawyers was consulted. Soon the Council of Learned Societies too was sending questionnaires to hundreds of people in any way connected to the world of art. A pamphlet describing what was known about German looting activity was prepared for distribution to members of Congress, which, it was hoped, would lead to hearings before the Foreign Relations Committee,

and increase pressure for the establishment of a high-level government art-protection body.

Taylor, Finley, and Co. were, by late April 1943, quite sure that recognition of their commission was only a matter of time. Taylor now faced a dilemma, for rumor had it that President Roosevelt himself had wished the energetic director of the Met to be appointed art adviser to the Supreme Allied Commander, with the grand rank of Colonel. The fulfillment of Taylor’s desire to inspect Europe’s threatened monuments and be the advocate of their protection in the highest councils of the Allies seemed at hand. But, to the long-term amusement of his colleagues, the corpulent Taylor was rejected by the Army as too fat. In his place, John Walker at the National Gallery suggested Captain Mason Hammond, a classics professor from Harvard who had already been drafted and was working in Air Force Intelligence.

Hammond’s superior officers could not believe he would be released for such unimportant duty, and he himself had no idea what he would be asked to do when the orders did indeed arrive. On May 27 he called Wilhelm Koehler, an emigré German art historian working on the American Defense Harvard lists at Dumbarton Oaks, having heard rumors that he was somehow involved in monuments protection. From Koehler’s memo on this conversation it is clear that Hammond had never talked to Colonel Shoemaker (nor indeed did the latter know of Hammond’s appointment):

He will be sent to Algeria in a few days where he expects to get more detailed information about his commission which concerns protection of works of art. … An Advisory National Committee will be appointed very soon by the President, but he does not know any names; he, however, will be responsible directly to the General, not to any home organization or office. He is completely unprepared for his job and has no time to prepare himself before he leaves. He asks whether I can help him. I tell him briefly about the Committees … and Col. Shoemaker … Paul Clemen’s book (which we tried in vain to get for him)… about personal experiences during the first World War. … He is exceedingly grateful for everything, having been entirely ignorant of what I was able to tell him.

34

Desperate for more information, Hammond arranged to see Shoemaker the next morning. They got on very well, but bound as he was by secrecy, the Colonel could give the new Monuments officer no specific orders or even suggestions about what reference books might be of use in the field. Convinced that he was off to protect the monuments of Algeria, Hammond departed on June 3 to take up his undefined duties.

Hammond’s conversation with Koehler does reveal that the committees

had inserted a foot in the Presidential door. It only remained for them to be formally recognized. On June 21 Secretary of State Cordell Hull signed an updated version of a letter which David Finley had drafted for him in April and managed to get it onto Roosevelt’s desk. FDR initialled it “OK” within forty-eight hours, and the American Commission for the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments in War Areas was finally a reality.

35

The only trouble was that the official announcement of its creation would not be made until August 20, and by then a lot would have happened. In the meantime, its existence remained a dread secret, and the already established nongovernmental groups carried on with the tasks assigned them.

They had plenty to do. On June 27 the HUSKY planners had cabled the Civil Affairs Division to “please obtain and send immediately by fast air mail material on public monuments of Italy, including Sicily and Sardinia particularly.” The “Harvard” lists for these areas had been delivered to the War Department on June 12. Apologizing that they had been “hastily compiled” and were “preliminary,” the CAD dispatched four copies on July 2. One week later the planners approved the idea of also supplying field units with maps on which the listed monuments would be clearly marked. Work on these, known as the Frick maps, began immediately in New York.

36

No one involved realized that brand-new military maps of Sicily were rolling off the presses at that very moment, based on new aerial surveys brought in only the week before by a reconnaissance squadron commanded by the President’s son, Elliott Roosevelt.

On June 7 Mason Hammond arrived in Algiers, where, to his amazement, it was revealed to him that he was to concern himself not with North Africa, but with Sicily. He was sent directly to a training and planning center at Chrea, in the mountains some forty miles south of Algiers, where the future Allied Military Government of Sicily (housed in a hotel, a former children’s sanitarium, and a ski club) was organizing itself in great secrecy, quite removed from the combat elements which would precede it. The basic regulations of this enterprise were being compiled into a handbook known as the AMGOT (Allied Military Government) “Bible.” To this, Hammond, not being in possession of any of the materials being prepared so assiduously at home by his academic colleagues, added what he could on the handling of works of art and the basic protection of buildings.

The collegial atmosphere of the center, in which each officer could discuss his discipline with his peers, enabled him to gain a degree of sympathy for his area of responsibility, though many “regarded the inclusion of cultural protection in a military operation with a certain amount of humorous

scorn.” The main problem was information, the invasion being veiled in such secrecy that Hammond could not use any of the research facilities available in Algiers. The only reference book in all of Chrea, the

Italian Touring Club Guide for Sicily

, was in equally heavy demand by other officers for details of population and geography.

Despite these limitations, he managed to produce a short history of the island and a list of the most important sites. When Major General The Lord Rennell of Rodd, the British military governor-designate, would not allow these to be reproduced and distributed for reasons of security, Hammond resorted to the spoken word: “I advised all men to whom I talked to secure local guides … or to find out from local authorities what monuments were in their districts.” Reaction to these naive instructions seemed favorable. But as the date for the invasion approached, Hammond remained alone—his British counterpart having never been appointed—and frustrated, with little to do, painfully aware that his lowly rank precluded his advice from being heard in the highest quarters, and that the directives for the invasion merely required that works of art, churches and archives be “protected” without providing specific instruction for doing so to field officers.

37

On July 5 the thousands of separate elements required for the Sicilian invasion had finally been assembled aboard more than two thousand ships of every size, and the greatest armada in military history set forth toward its objective, still unannounced to the majority of its passengers. Emotions ran high as one of the headquarters ships sailed out of harbor past color guards and buglers of both nations. Despite a violent storm, which hit the fleet en route, the landings on the south coast of Sicily were successful. The terrible weather had hidden the Allied approach, and initial resistance by Italian forces was not fierce—everyone noticed that the Sicilians acted more as if they were being liberated than attacked.

But the German troops in the interior were not of the same mind, and after the first euphoric days the real fighting, which would last until the fall of Messina nearly six weeks later, began, and with it revelations of the flaws in the newly created Allied organizations. To Ernie Pyle, covering the fighting, it seemed that “everything in this world had stopped except war and we were all men of a new profession out in a strange night.”

38

Nowhere would this be truer than among those responsible for Military Government.

For nearly three weeks after the landing, receiving only vague reports of events, Hammond languished in the Algerian staging area at Tizi Ouzu, a school building surrounded by barbed wire where, as a later Monuments

officer commented, the “British cooking and the French plumbing” were equally deplorable.

39

During this limbo period, though frustrated by the delay, Hammond had as yet no major feelings of inadequacy, and wrote to a colleague: “I doubt if there is need for any large specialist staff for this work, since it is at best a luxury and the military will not look kindly on a lot of art experts running around trying to tell them what not to hit. However, the Adviser (for Sicily, one perhaps enough, for larger spheres probably several) should have rank enough to carry weight in staff counsels and be able to get things done in the field. They should be provided with transportation. How far they will need a secretarial staff is hard to say.”

40

He would soon find out.

On July 29 Hammond finally arrived at his assigned headquarters in Syracuse. While inspecting the local monuments—the main danger to which seemed to be the use of ancient catacombs as bomb shelters by the local population, who had rearranged the relics to make life more comfortable—he was delighted to find the local Superintendent of Antiquities on the job. But before he could do much of anything, the headquarters was ordered to move on to Palermo, which had fallen to Patton’s troops only on July 22. On his circuitous route from Syracuse to Palermo, made necessary by fierce German resistance in the center of the island, Hammond managed a brief glimpse of the Greek temples at Agrigento, their ruins “undamaged” to his practiced eye. Less experienced officers had trouble with such classical remains. In one of the few apocryphal monuments stories, Patton, having taken the warnings on preservation in the invasion directives to heart, was reputed to have angrily demanded of a local resident if the roofless temple before him had been damaged by American artillery. “No,” answered the farmer through an interpreter. “That was done during the last war.” Patton, who considered himself a history buff, was puzzled. “Last war?” he asked. “When was that?” “Oh, that,” replied the Italian, “that was the second Punic War.”

41

Although professional soldiers such as Omar Bradley did not consider damage in the ancient port city of Palermo particularly serious, the press and Civil Affairs officers were shocked. It was the first city most had seen which had undergone systematic bombing. The Allied Air Forces had concentrated their efforts there in order to distract attention from the actual landing sites in the south.

Herald Tribune

correspondent Homer Bigart reported: “There is scarcely a block in which one or more of the massive stone buildings has not been reduced to dust and rubble…. The crumpled buildings are like a lane of grotesque tombs in the moonlight.”

42

It was hard to know where to begin; but Hammond was greeted upon arrival by a committee of Italian museum and library officials, amazingly

already set up in the chaos by Lord Rennell, the British Military Government chief. From them he learned that the great Norman monuments of the city and its environs, including the magnificent twelfth-century cathedral and cloister at Monreale, were intact, though more than sixty other churches and the National Library had been damaged. No one had been paid for months, and funds were needed for emergency repairs. Nor were the newly conquered Sicilians shy about demanding such financing. This thorny situation and the basic problems of logistics would keep him firmly tied to Palermo.

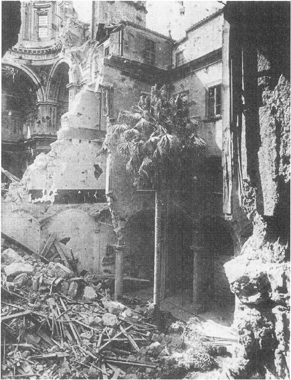

The damaged Museo Nazionale, Palermo. In the background, ruins of Chiesa dell’Olivella.

The working conditions of the entire Military Government were appalling. Hammond’s office contained only a chair and a desk; he had no clerical help, no typewriter, and worst of all no transportation. (Indeed,

Herald Tribune

reporters had observed many Civil Affairs officers hitch-hiking

from one liberated town to another.) His expected British colleague had still not appeared. Fortunately he had brought his own typewriter, upon which he composed letters to the Italian authorities in a unique blend of classical Latin and the modern tongue, providing them with hilarious relief to their often grim duties. The office was also occupied by the public relations officer, and there were moments when “it resembled a madhouse, with one officer trying to satisfy the demands of newspaper correspondents and the other trying to talk Italian to two or three Superintendents at the same time.”

Other books

Shadows Still Remain by Peter de Jonge

The Canning Kitchen by Amy Bronee

To Find You Again by Maureen McKade

Anything for a 'B' (MF) by Francis Ashe

KRISHNA CORIOLIS#1: Slayer of Kamsa by Ashok K. Banker

Southampton Spectacular by M. C. Soutter

Lifesaving for Beginners by Ciara Geraghty

9781631053566SpringsDelightBallNC by Kathleen Ball

Truth or Dare (Liar Liar #2) by C.A. Mason

The Healing Wars: Book II: Blue Fire by Janice Hardy