The Rape of Europa (82 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

Outrageous behavior was not limited to Germans. The Yugoslav representative at the Munich Collecting Point, a Mr. Topic, falsely claimed 165 paintings, which as of 1960 had not been recovered.

50

But this was a mere skirmish compared to the years-long battle for the disposition of the Italian works held at the Collecting Points.

Restitution to Germany’s former ally had been put off to the very last. In due course such clearly looted items as the Naples pictures from Monte Cassino were returned, as were the contents of the great German Art Historical Institutes whose founders had specifically required that they be in Italy. But the works given to Hitler and Goering by Mussolini or bought by them on the Italian market, which John Walker had hoped might come to the United States, were a different question. Stewart Leonard, director of the Munich Collecting Point in 1947, did not believe they should be returned. In this he was strongly backed by his German colleagues, some of whom wrote long righteous papers explaining why the works should stay in Germany. Opposing the holders of these opinions was the colorful and mysterious self-appointed savior of the Italian patrimony, Rodolfo Siviero.

Siviero was said to have formed a secret unit dedicated to art protection which had worked all over Italy with regional units of the Partisans. Agents of this group had penetrated the Italian Fascist secret police and after the German takeover were able to monitor German cable traffic. They had therefore known of the intentions of the Kunstschutz to remove art works to the north, but had been powerless to stop the transfer alone,

and had, according to Siviero, secretly warned the Allied command of the plot.

51

This information does not seem to have reached the proper authorities. When the Allies took Siena in 1944, Siviero offered his services to Deane Keller, but the MFAA officer, not sure of the Italian’s motives or politics, put him off. Siviero approached Keller again in Florence, volunteering to “involve himself” with the Americans in the recovery of the missing Uffizi treasures, but this time the Counter Intelligence Corps rejected the offer.

52

Siviero was next heard from in 1948 in his capacity as chief of the Italian recuperation effort, presenting to the U.S. Military Government a claim not only for the works given away by Mussolini but for those bought by the Nazis from Contini and other Italian dealers. In 1946 the Italian government had declared all transactions made under “political pressure” as null and void. It seemed logical that the United States should return all works of art identifiable as being of Italian origin to Italy, as had already been done for Austria and everyone else. But in the eyes of the United States, Austria and Italy were not in the same category. Austria, despite its enthusiastic welcome of the Führer, was regarded as an “overrun” nation, not as an Axis ally, but because of voluntary alliance with Germany up to 1943, Italy’s claim was not considered as automatic.

This idea was intolerable to Siviero, who now began an all-out campaign. The items in question he described as having been “exported from Italy in a clandestine manner or sold or donated in violation of the Italian law.”

53

He did not limit himself to communication with the Military Government, but made sure that the American State Department and the Italian press heard about it too. Collecting Point director Leonard (who later admitted that his own attitude was “intransigent”

54

) and the Germans produced reams of documents showing that many of the works claimed were not national treasures; that many were not even of Italian origin, having been offered on the market in other countries before being brought to Italy; and that the sales had not been at all secret. Soon the argument came to the notice of General Clay, now deeply embroiled in the Berlin Airlift. His fervent desire to rid himself of yet more art was augmented by the need to promote pro-Western policies in Italy, which, many feared in 1948, might go Communist. Clay therefore ordered the immediate return of the works requested by Siviero.

55

Stewart Leonard refused to carry out the order, going so far as to produce negative documentation. He had some success: Clay compromised but ordered thirty-nine of the hundred-plus pictures sent off while the rest were being investigated. Leonard was so upset that he resigned and sailed for home, but not before he had sent further protests to the Legal Division

of the State Department. The Corsini Memling

Portrait of a Gentleman

, the Spiridon

Leda and the Swan

(at that time attributed to Leonardo), and sixteen other works were shipped out by Leonard’s hastily appointed successor, Stephen Munsing. In their coverage of the event, the German newspapers referred to Siviero as a “pirate who takes advantage of the political situation.”

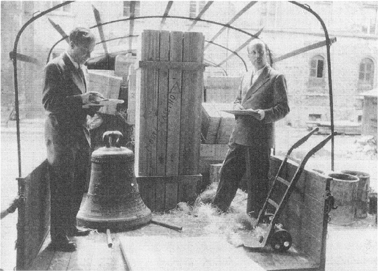

Rodolfo Siviero

(right)

receives Naples masterpieces removed from Monte Cassino from Monuments officer Edgar Breitenbach.

Before any more pictures could be dispatched, the effect of Leonard’s protests on the State Department, sensitized by the dramas of the 202, became clear. They did not have the result he intended. Over the signature of Acting Secretary of State Lovett came a long telegram deploring rumors that “proposals for the sale of works of art for purposes of relief are being increasingly advanced.” The United States government should never, he said, “directly or indirectly aid in the sale and dispersal of art from Europe.” The cable included rumors that “French dealers are attempting to gain access to the collecting points on the ostensible grounds of aiding in the identification of art” and that “certain American museum officials are openly advocating the sale of objects from Nazi and German public collections”—the source for the latter being a remark by Theodore Rousseau,

who had left the OSS to become curator of paintings at the Met, quoted in

The New Yorker:

America has a chance to get some wonderful things here during the next few years. German museums are wrecked and will have to sell. … I think it’s absurd to let the Germans have the paintings the Nazi big-wigs got, often through forced sales, from all over Europe. Some of them ought to come here, and I don’t mean especially to the Metropolitan, which is fairly well off for paintings, but to museums in the West which aren’t.

Lovett’s cable ended with a demand for a public statement from Munich denying that any such policy was contemplated.

56

Meanwhile, in Italy, Siviero had announced to the press that he had “won a diplomatic victory over the Americans in Berlin and overcome German sabotage in Munich” by recovering national treasures which the unprincipled Nazis had stolen “shortly before we heroically eliminated them from our country in 1945.” This revisionism was too much for Monuments officer Theodore Heinrich, who happened to be in Florence. He confronted Siviero, threatening to take the matter up with the American embassy, and forced him to make a public retraction.

57

Siviero now returned to Munich to pursue his quest for the rest of the objects on his list. He bribed German staff at the Collecting Point to tell him what was there and even tried to influence director Munsing by offering him a luxurious trip to Italy.

58

But he overplayed his hand; on June 1, 1949, his credentials were withdrawn on the grounds that “Mr. Siviero is reported to be a Communist who is conducting a virulent press campaign against U.S. restitution policy and who has spread many untruths concerning the U.S. government, the Munich Collecting Point and the personnel attached thereto.”

59

Nothing daunted, Siviero continued his campaign from Italy. Things escalated to such a degree that 125 German employees at the Collecting Point sent a petition to President Truman. This was answered by an equally fiery broadside signed by the intellectual members of Italy’s ancient Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei. The Italian government hastily removed Siviero “from further duty in connection with this activity because it was found that he could not deal successfully with the Americans and because he had entered into press polemics which proved embarrassing to the Italian government.”

60

It all died down for a time, but a year later Siviero was back in the fray. His insistence on the illegality of some sales was considerably weakened, in the view of his opponents, by the circumstances surrounding the disposition of the Spiridon

Leda.

Once it had returned to Italy it had not been

given to the former owner, the Countess Margaretha Spiridon-Callotti, but had been kept by the Italian state. The Countess had sued for its return, asserting that the painting had been “extorted” from her in 1941; but an investigation by Siviero had led to charges against her for attempting to defraud the state. In its case against the Countess the Italian government now used the exact same arguments as had the Collecting Point officials: that the picture had not even been brought to Italy until 1939, and then for purposes of sale. To this they added the gossipy accusations that the Countess had celebrated the event with a party, had thrown in a Leonardo drawing for the Führer, and had invested her ill-gotten gains in the palatial former residence of Barbara Hutton known as the Abbey of San Gregorio.

61

The State Department now backed the Collecting Point officers, and nothing more was returned to Italy by them.

Siviero never changed his tune. Whenever possible he belittled the American role in the recovery of the Uffizi treasures and took the credit for himself, bringing forth periodic protests from former Monuments men. But for Italy his persistence was successful. In 1953, after the departure of the Americans, a special accord with the Adenauer government brought back most of the remaining objects on his list. Indefatigable and obsessed, he continued until his death in 1983 to hunt down art taken from Italy. Along the way his glory came from a series of exhibitions of recovered works which culminated in a posthumous one in his honor at the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. The lavish catalogue repeats all Siviero’s mythic themes, which, as was his custom, are embellished by a number of amusing variations.

Long after the American Monuments officers had left Germany, Rose Valland, like her Italian counterpart, continued her quest to retrieve or account for every single thing that had left France. She too had her days of glory: André Malraux awarded her the Légion d’honneur and the Medal of the Resistance. In 1964 her story was revealed, rather inaccurately, to the world in a film entitled

The Train

, which starred Paul Scofield as von Behr, Burt Lancaster as the Resistance Hero, and the glamorous Suzanne Flon as Rose. But after a time her persistence and her knowledge of collaboration and shady deals began to make her unpopular among those not wishing to be reminded of the events of the war. She was particularly reluctant to set a final date for claims on the unidentified and not very high-grade leftovers which remained after the better objects had been distributed among the museums. These had become an administrative headache for everyone, and many felt they should be sold. By 1965 Mlle Valland’s stubbornness had driven the director of the Musées de France to suggest to her

that it might be time to look forward to peace and fraternity, forget the past, and leave the disposition of the works to the living, which “would take nothing away from the respect for the dead.”

62

But Resistance heroine Valland never would compromise, and in her last years retreated entirely into her world of secret documents, which at her death were relegated, unsorted and chaotic, to a Musées storeroom in Malmaison.

In Germany as well, the dedicated continued to search. Wilhelm Arntz, a lawyer, spent years trying to track down every single “degenerate” picture removed by the Nazis, in the process uncovering considerable unsavory activity by auctioneers, dealers, and museums. Kurt Reutti, who had started the Zentralstelle in Berlin, scoured the East German countryside, travelling hobolike from place to place in empty boxcars or whatever vehicle he could find. His reception was sometimes mixed: in one village two ladies defended their possession of a stolen picture with pickax and shovel, while another gently led him to her house, where he was amazed to find the Kadolzburg altar from the Erasmus Chapel of the Berliner Schloss. The Russians had thrown it on the ground, and the old lady had saved it because she “could not let the Lord God just lie there.” Most extraordinary was his discovery of a group of large Chinese temple figures missing from the collections of Baron von der Heydt. These he traced to a remote house in Angermünde, northeast of Berlin on the Polish border. Upon arriving Reutti was told that the “Chinese stuff” was on the dump:

Other books

Rocked Under by Cora Hawkes

Autumn Street by Lois Lowry

Everran's Bane by Kelso, Sylvia

Sweet Release (A Bad Boy Mafia Romance) by Victoria Villeneuve

Do the Birds Still Sing in Hell? by Horace Greasley

Going Down by Shelli Stevens

Wolf’s Heart by Ruelle Channing, Cam Cassidy

Bound (Secrets of the Djinn) by Lamer, Bonnie

Falling Into You by Jasinda Wilder

The Wounded Nobleman (The Regimental Heroes) by Conner, Jennifer