The Rational Optimist (24 page)

Read The Rational Optimist Online

Authors: Matt Ridley

In technical jargon, the entire world is experiencing the second half of a ‘demographic transition’ from high mortality and high fertility to low mortality and low fertility. It is a process that has occurred in many countries, starting with France at the end of the eighteenth century then spreading to Scandinavia and Britain in the nineteenth century and to the rest of Europe in the early twentieth century. Asia began to follow the same path in the 1960s, Latin America in the 1970s and most of Africa in the 1980s. It is now a worldwide phenomenon: with the exception of Kazakhstan, there is no country where birth rate is high and rising. The pattern is always the same: mortality falls first, causing a population boom, then a few decades later, fecundity falls quite suddenly and quite rapidly. It usually takes about fifteen years for birth rate to fall by 40 per cent. Even Yemen, the country with the highest birth rate in the world for most of the 1970s with an average of nearly nine babies per woman, has halved the number. Once the demographic transition starts happening in a country it happens at all levels of society pretty well at the same time.

Not everybody saw the demographic transition coming, but some did. When the journalist John Maddox wrote a book in 1973 arguing that the demographic transition was already slowing Asian birth rates, he was treated to a condescending blast by Paul Ehrlich and John Holdren:

The most serious of Maddox’s many demographic errors is his invocation of a ‘demographic transition’ as the cure for population growth in Asia, Africa and Latin America. He expects that birth rates there will drop as they did in developed countries following the industrial revolution. Since most underdeveloped countries are unlikely to have an industrial revolution, this seems somewhat optimistic at best. But even if those nations should follow that course, starting immediately, their population growth would continue for well over a century – perhaps producing by the year 2100 a world population of twenty thousand million.

Rarely has a paragraph proved so wrong so soon.

An unexplained phenomenon

Deliciously, nobody really knows how to explain this mysteriously predictable phenomenon. Demographic transition theory is a splendidly confused field. The birth-rate collapse seems to be largely a bottom-up thing that emerges by cultural evolution, spreads by word of mouth, and is not commanded by fiat from above. Neither governments nor churches can take much credit. After all, the European demographic transition happened in the nineteenth century without any official encouragement or even knowledge. In the case of France, it happened in the teeth of official encouragement to breed. Likewise, the modern transition began without any government family-planning policies in many countries, especially Latin America. China’s highly coerced (‘one child’) birth-rate decline since 1955 (from 5.59 to 1.73 children, or 69 per cent) is almost exactly mirrored by Sri Lanka’s largely voluntary one over the same time period (5.70 to 1.88, or 67 per cent). As for religion, Italy’s plunging birth rate (now 1.3 children per woman) in the pope’s backyard has always seemed moderately amusing to non-Catholics. Of course, the provision of family planning advice surely helps, and in parts of Asia may have accelerated the transition, but on the whole it seems to help women cheaply and easily achieve what they wish to achieve anyway. The onset of Britain’s demographic transition in the 1870s coincided with the publication of bestsellers on contraception by Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh – but which caused which?

So what might be the cause of these episodes of quite extraordinary downward shift in human fecundity? Top of the list of explanations, paradoxically, comes falling child mortality. The more babies are likely to die, the more their parents bear. Only when women think their children will survive do they plan and complete their families rather than just keep breeding. This remarkable fact seems to be very poorly known. Most Western, educated people seem to think, rationally enough, that keeping babies alive in poor countries is only making the population problem worse and that ... well, the implication is usually left unspoken. Jeffrey Sachs recounts that on ‘countless occasions’ after a lecture a member of the audience has ‘whispered’ to him ‘if we save all those children, won’t they simply starve as adults?’ Answer: no. If we save children from dying, people will have smaller families. In Niger or Afghanistan today, where more than fifteen of every 100 babies die before their first birthdays, the average woman will give birth seven times in her lifetime; in Nepal and Namibia, where less than five babies out of every 100 die, the average woman gives birth three times. But the correlation is not exact. Burma has twice the infant mortality and half the birth rate of Guatemala, for instance.

Another factor is wealth. Having more income means you can afford more babies, but it also means you can afford more luxuries to divert you from constant breeding. Children are consumer goods, but rather time-consuming and demanding ones compared with, say, cars. The transition seems to kick in as countries grow richer, but there is no exact level of income at which it happens, and the poor and the rich within any country start reducing their birth rate about the same time. Once again, there are exceptions: Yemen has almost twice the birth rate and almost twice the income per head of Laos.

Is it female emancipation? Certainly, the correlation between widespread female education and low birth rate is pretty tight, and the high fecundity of many Arab countries must in part reflect women’s relative lack of control over their own lives. Probably by far the best policy for reducing population is to encourage female education. It is evolutionarily plausible that in the human species, females want to have relatively few children and give them high-quality upbringing, whereas males like to have lots of children and care less about the quality of their upbringing. So the empowerment of women through education gives them the upper hand. But there are exceptions here too: 90 per cent of girls complete primary school in Kenya, which has twice the birth rate of Morocco, where only 72 per cent of girls complete primary school.

Is it urbanisation? Certainly, as people move from farms, where children can help in the fields, to cities where housing is expensive and jobs are outside the home, they find large families to be a drawback. Most cities are – and always have been – places where death rates exceed birth rates. Immigration sustains their numbers. Yet this cannot be the whole story: Nigeria is twice as urbanised and twice as fecund as Bangladesh.

In other words, the best that can be said for sure about the demographic transition is that countries lower their birth rates as they grow healthier, wealthier, better educated, more urbanised and more emancipated. A typical woman probably reasons thus: now I know my children will probably not die of disease, I do not need to have so many; now I can get a job to support those children, I do not want to interrupt my career too often; now I have an education and a pay cheque, I can take control of contraception; now education can get my children non-farming jobs, I shall have only as many as I can support through school; now I can buy consumer goods, I shall be careful not to spread my income across too large a family; now I live in a city I will plan my family. Or some combination of such thoughts. And she will be encouraged by the examples of others, and by family-planning clinics.

To argue that the demographic transition is a mysterious, evolutionary, natural phenomenon, rather than a successful government policy, is not to say that it cannot be given a push. If Africa’s slow fall in birth rates could be accelerated, there would be great dividends in terms of welfare. A bold programme, driven by philanthropy or even government aid, but not tied to teaching sexual abstinence, to cut child mortality in countries like Niger, and hence bring forward the fall in family size, and to spread the news of family planning out to rural villages, could mean that Africa has 300 million fewer mouths to feed in 2050 than it otherwise would. However, politicians should be careful not to repeat in Africa the high-minded brutality that Asia experienced in the 1970s.

It is somewhat distasteful to the intelligentsia to accept that consumption and commerce could be the friend of population control, or that it is when they ‘enter the market’ as consumers that people plan their families – this is not what most market-phobic professors, preaching anticapitalist asceticism, want to hear. Yet the relationship is there, and it is strong. Seth Norton found that the birth rate was more than twice as high in countries with little economic freedom (average 4.27 children per woman) compared with countries with high economic freedom (average 1.82 children per woman). Besides, there is quite a neat exception which proves this rule. The Anabaptist sects in North America, the Hutterites and Amish, have largely resisted the demographic transition; that is to say, they have large families. This has been achieved despite – or rather because of – an ascetic emphasis on family roles, which immunises them against the spread of time-consuming hobbies (including higher education) and a taste for expensive gadgets.

What a happy conclusion. Human beings are a species that stops its own population expansions once the division of labour reaches the point at which individuals are all trading goods and services with each other, rather than trying to be self-sufficient. The more interdependent and well-off we all become, the more population will stabilise well within the resources of the planet. As Ron Bailey puts it, in complete contradiction of Garrett Hardin: ‘There is no need to impose coercive population control measures; economic freedom actually generates a benign invisible hand of population control.’

Most economists are now more worried about the effects of imploding populations than they are about exploding ones. Countries with very low birth rates have rapidly ageing workforces. This means more and more old people eating the savings and taxes of fewer and fewer people of working age. They are right to be concerned, though they would be wrong to be apocalyptic, after all, today’s 40-year-olds will surely be happier to continue operating computers in their seventies than today’s 70-year-olds are to continue operating machine tools. And once again, the rational optimist can bring a measure of comfort. The latest research uncovers a second demographic transition in which the very richest countries see a slight increase in their birth rate once they pass a certain level of prosperity. The United States, for example, saw its birth rate bottom out at 1.74 children per woman in about 1976; since then it has risen to 2.05. Birth rates have risen in eighteen of the twenty-four countries that have a Human Development Index greater than 0.94. The puzzling exceptions are ones such as Japan and South Korea, which see a continuing decline. Hans-Peter Kohler of the University of Pennsylvania, who co-authored the new study, believes that these countries lag in providing women with better opportunities for work–life balance as they get richer.

So, all in all, the news on global population could hardly be better, though it would be nice if the improvements were coming faster. The explosions are petering out; and the declines are bottoming out. The more prosperous and free that people become, the more their birth rate settles at around two children per woman with no coercion necessary. Now, is that not good news?

The release of slaves: energy after 1700

With coal almost any feat is possible or easy; without it we are thrown back in the laborious poverty of earlier times.

S

TANLEY

J

EVONS

The Coal Question

In 1807, as Parliament in London was preparing to pass at last William Wilberforce’s bill to abolish the slave trade, the largest factory complex in the world had just opened at Ancoats in Manchester. Powered by steam and lit by gas, both generated by coal, Murrays’ Mills drew curious visitors from all over country and beyond to marvel at their modern machinery. There is a connection between these two events. The Lancashire cotton industry was rapidly converting from water power to coal. The world would follow suit and by the late twentieth century, 85 per cent of all the energy used by humankind would come from fossil fuels. It was fossil fuels that eventually made slavery – along with animal power, and wood, wind and water – uneconomic. Wilberforce’s ambition would have been harder to obtain without fossil fuels. ‘History supports this truth,’ writes the economist Don Boudreaux: ‘Capitalism exterminated slavery.’

The story of energy is simple. Once upon a time all work was done by people for themselves using their own muscles. Then there came a time when some people got other people to do the work for them, and the result was pyramids and leisure for a few, drudgery and exhaustion for the many. Then there was a gradual progression from one source of energy to another: human to animal to water to wind to fossil fuel. In each case, the amount of work one man could do for another was amplified by the animal or the machine. The Roman empire was built largely on human muscle power, in the shape of slaves. It was Spartacus and his friends who built the roads and houses, who tilled the ground and trampled the grapes. There were horses, forges and sailing ships as well, but the chief source of watts in Rome was people. The period that followed the Roman empire, especially in Europe, saw the widespread replacement of that human muscle power by animal muscle power. The European early Middle Ages were the age of the ox. The invention of dried-grass hay enabled northern Europeans to feed oxen through the winter. Slaves were replaced by beasts, more out of practicality than compassion one suspects. Oxen eat simpler food, complain less and are stronger than slaves. Oxen need to graze, so this civilisation had to be based on villages rather than cities. With the invention of the horse collar, oxen then gave way to horses, which can plough at nearly twice the speed of an ox, thus doubling the productivity of a man and enabling each farmer either to feed more people or to spend more time consuming other’s work. In England, horses were 20 per cent of draught animals in 1086, and 60 per cent by 1574.

In turn oxen and horses were soon being replaced by inanimate power. The watermill, known to the Romans but comparatively little used, became so common in the Dark Ages that by the time of the Domesday Book (1086), there was one for every fifty people in southern England. Two hundred years later, the number of watermills had doubled again. By 1300 there were sixty-eight watermills on a single mile of the Seine in Paris, and others floating on barges.

The Cistercian monastic order took the watermill to its technical zenith, not only improving and perfecting it, but aggressively suppressing rival animal-powered mills by legal action. With gears, cams and trip hammers, they used the water to achieve multiple ends. At Clairvaux, for example, the water from the river first turned the mill wheel to crush the grain, then shook the sieve to separate flour from bran, then topped up the vats to make beer, then moved on to work the fullers’ hammers against the raw cloth, then trickled into the tannery and was finally directed to where it could wash away waste.

The windmill appeared first in the twelfth century and spread rapidly throughout the Low Countries, where water power was not an option. But it was peat, rather than wind, that gave the Dutch the power to become the world’s workshop in the 1600s. Peat dug on a vast scale from freshly drained bogs fuelled the brick, ceramic, beer, soap, salt and sugar industries. Harlem bleached linen for the whole of Germany. At a time when timber was scarce and expensive, peat gave the Dutch their chance.

Hay, water and wind are ways of drawing upon the sun’s energy: the sun powers plants, rain and the wind. Timber is a way of drawing on a store of the sun’s energy laid down in previous decades – on solar capital, as it were. Peat is an older store of the sunlight – solar capital laid down over millennia. And coal, whose high energy content enabled the British to overtake the Dutch, is still older sunlight, mostly captured around 300 million years before. The secret of the industrial revolution was shifting from current solar power to stored solar power. Not that human muscle power disappeared: slavery continued, in Russia, the Caribbean and America as well as many other places. But gradually, erratically, more and more of the goods people made were made with fossil energy.

Fossil fuels cannot explain the start of the industrial revolution. But they do explain why it did not end. Once fossil fuels joined in, economic growth truly took off, and became almost infinitely capable of bursting through the Malthusian ceiling and raising living standards. Only then did growth become, in a word, sustainable. This leads to a shocking irony. I am about to argue that economic growth only became sustainable when it began to rely on non-renewable, non-green, non-clean power. Every economic boom in history, from Uruk onwards, had ended in bust because renewable sources of energy ran out: timber, crop land, pasture, labour, water, peat. All self-replenishing, but far too slowly, and easily exhausted by a swelling populace. Coal not only did not run out, no matter how much was used: it actually became cheaper and more abundant as time went by, in marked contrast to charcoal, which always grew more expensive once its use expanded beyond a certain point, for the simple reason that people had to go further in search of timber. Had England never used coal, it could still have had an industrial miracle of sorts, because it could have (and did) use water power to drive the frames and looms that turned Lancashire into the cotton capital of the world. But water power, though renewable, is very much finite, and Britain’s industrial boom would have petered out as expansion became impossible, population pressure overtook income and wages fell, depressing demand.

This is not to imply that non-renewable resources are infinite – of course not. The Atlantic Ocean is not infinite, but that does not mean you have to worry about bumping into Newfoundland if you row a dinghy out of a harbour in Ireland. Some things are finite but vast; some things are infinitely renewable, but very limited. Non-renewable resources such as coal are sufficiently abundant to allow an expansion of both economic activity and population to the point where they can generate sustainable wealth for all the people of the planet without hitting a Malthusian ceiling, and can then hand the baton to some other form of energy. The blinding brightness of this realisation still amazes me: we can build a civilisation in which everybody lives the life of the Sun King, because everybody is served by (and serves) a thousand servants, each of whose service is amplified by extraordinary amounts of inanimate energy and each of whom is also living like the Sun King. I will deal in later chapters with the many objections that pessimistic environmentalists will raise, including the question of the atmosphere’s non-renewable capacity for absorbing carbon dioxide.

Wealthier yet and wealthier

Before I make the case that fossil fuels, by driving pistons and dynamos, made modern living standards possible, first, a digression about living standards. Did industrialisation really improve them? There are still people about, including it seems those who write the textbooks from which my children learn history, who follow Karl Marx in believing that the industrial revolution drove down most living standards, by cramming carefree and merrie yokels into satanic mills and polluted tenements, where they were worked till they broke and then coughed their way to early deaths. Is it really necessary to point out that poverty, inequality, child labour, disease and pollution existed before there were factories? In the case of poverty, the rural pauper of 1700 was markedly worse off than the urban pauper of 1850 and there were many more of him. In Gregory King’s survey of the British population in 1688, 1.2 million labourers lived on just £4 a year and 1.3 million ‘cottagers’ – peasants – on just £2 a year. That is to say, half the entire nation lived in abject poverty; without charity they would starve. During the industrial revolution, there was plenty of poverty but not nearly as much as this nor nearly as severe. Even farm labourers’ income rose during the industrial revolution. As for inequality, in terms of both physical stature and number of surviving children, the gap narrowed between the richest and the poorest during industrialisation. That could not have happened if economic inequality increased. As for child labour, a patent for a hand-driven linen-spinning machine from 1678, long before powered mills, happily boasts that ‘a child three or four years of age may do as much as a child of seven or eight years old.’ As for disease, deaths from infectious disease fell steadily throughout the period. As for pollution, smog undoubtedly increased in industrial cities, but the sewage-filled streets of Samuel Pepys’s London were more noisome than anything in Elizabeth Gaskell’s Manchester of the 1850s.

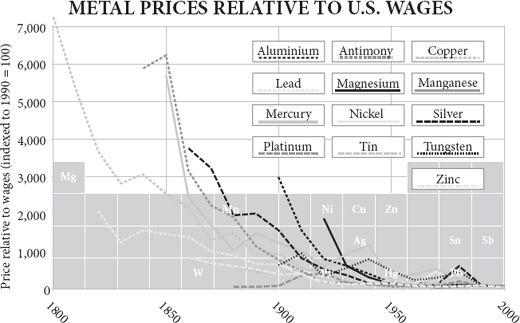

The plain fact is that the mechanisation of production in the industrial revolution raised incomes across all classes. The average Englishman’s income, having apparently stagnated for three centuries, began to rise around 1800 and by 1850 was 50 per cent above its 1750 level, despite a trebling of population. The rise was steepest for unskilled workers: the wage premium for skilled building workers fell steadily. Income inequality fell, and gender inequality, too. The share of national income captured by labour rose, while the share captured by land fell: the rent of an acre of English farmland buys as many goods now as it did in the 1760s, while the real wage of an hour of work buys immensely more. Real wages rose faster than real output throughout the nineteenth century, meaning that the benefit of cheaper goods was being garnered chiefly by the workers as consumers, not by bosses or landlords. That is to say, the people who produced manufactured goods could also increasingly afford to consume them.

While it is undoubtedly true that by modern standards the workers who manned the factories and mills of 1800 in England laboured for inhuman hours from an early age in conditions of terrible danger, noise and dirt, returning to crowded and insanitary homes through polluted streets, and had dreadful job security, diet, health care and education, it is none the less just as undeniably true that they lived better lives than their farm-labourer grandfathers and wool-spinning grandmothers had done. That was why they flocked to the factories from the farms – and would do so again in New England in the 1870s, in the American South in the 1900s, in Japan in the 1920s, in Taiwan in the 1960s, in Hong Kong in the 1970s and in China today. That was why the jobs in the mills were denied to the Irish in New England and the blacks in North Carolina.

Here are three anecdotes to illustrate the notion that factory jobs are often preferable to farm ones. A farm worker named William Turnbull, born in 1870, told my grandmother that he started work at thirteen, for sixpence a day, working six days a week, from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., usually outdoors whatever the weather, with just Good Friday, Christmas Day and half of New Year’s day as his only holidays. On market days he started herding sheep or cattle to town, carrying a lantern, at 1 or 2 a.m. A cotton picker from North Carolina in the 1920s explained to a different historian why the mill was so much better than the farm: ‘Once we went to work in the mill after we moved here from the farm, we had more clothes and more kinds of food than we did when we was a-farmin’. And we had a better house. So yes when we came to the mill life was easier.’ And in the 1990s Liang Ying was delighted to run away from the family rubber farm in southern China, where she had daily to cut the bark of hundreds of rubber trees in pre-dawn darkness, to get a job at a textile factory in Shenzhen: ‘If you were me, what would you prefer, the factory or the farm?’ The economist Pietra Rivoli writes, ‘As generations of mill girls and seamstresses from Europe, America and Asia are bound together by this common sweatshop experience – controlled, exploited, overworked, and underpaid – they are bound together too by one absolute certainty, shared across both oceans and centuries: this beats the hell out of life on the farm.’

The reason that the poverty of early industrial England strikes us so forcibly is that this was the first time writers and politicians took notice of it and took exception to it, not because it had not existed before. Mrs Gaskell and Mr Dickens had no equivalents in previous centuries; factory acts and child labour restrictions were unaffordable before. The industrial revolution caused a leap in the wealth-generating capacity of the population that greatly outstripped its breeding potential but it thereby also caused an increase in compassion, much of which was expressed through the actions of charities and governments.