The Real Custer (48 page)

Authors: James S Robbins

On August 4, Custer, with A and B troops under command of Myles Moylan, was scouting west of the main column at Honsinger Bluff, seven miles west of the juncture of the Tongue and Yellowstone Rivers. Tom Custer and James Calhoun were also along, and the group totaled around one hundred men. It was a hot, sunny day, the temperature over 95 degrees. The day was uneventful, and after finding a suitable camp for the column on the floodplain of the Yellowstone with plenty of wood, he and his men relaxed, eating, napping, fishing, and grazing their horses.

After noon, Custer's pickets spied six Indians approaching. He was napping under a tree and awoke to the shout of “Indians! Indians!” followed by gunfire.

19

Custer ordered his men to mount, and he, Calhoun, and an orderly immediately gave chase, with Tom Custer following with a platoon of horsemen. Moylan then began to come up with the rest. The Indians headed for a wooded area two miles west of

where Custer had stopped. But they were not fleeing very vigorously, and George sensed a trick.

Custer stopped the pursuit, and the fleeing Indians paused. Then over 250 mounted warriors broke from the woods, charging toward the cavalrymen. Indian scouts had spotted Custer's men earlier in the morning, and Hunkpapa Sioux from Sitting Bull's encampment of four hundred to five hundred lodges, west near Locke Bluff, had gathered in the woods for battle. Among them were war leader Rain-in-the-Face, a contingent of Oglala Sioux, and some Miniconjou and Cheyenne. By some accounts, the Sioux were led by Crazy Horse.

Tom Custer formed a skirmish line and opened up on the charging as George and the other two raced back. This slowed the Indian advance, giving time for the command to set up a defense in the woods where they had been resting. The dismounted cavalrymen formed an arc along a former streambed and opened fire with the Indians at four hundred yards. The Indians stopped and began exchanging fire with the troopers, to little effect on either side.

The Indian ambush had failed, but they had come to fight, and they sought various ways to break Custer's defense. A group tried to sneak up the riverbank and into Custer's rear to stampede the horses but were detected and driven off. They set fire to the grass to raise a smoke screen to cover their movements, but this also failed. The battle became an exchange of potshots that wore on for hours. Custer hunkered down, waiting for the advancing column to respond to the sound of the fight.

Some miles downstream from the battlefield, veterinary surgeon Doctor John Holzenger and sutler Augustus Baliran were hunting for fossils. Two privates were nearby, John Ball and another named Brown, the latter of whom was napping. Scout Charley Reynolds rode up and warned them there were Indians in the area and they should make for safety. But the area was rich in fossils, so they kept up their hunt. A short

time later, several Indians, part of a scouting party led by Rain-in-the-Face, jumped from hiding, dragged Doctor Holzenger from his horse, and shot him. They then killed Baliran and Ball. Brown, roused from sleep, saw what was happening and leapt on his horse bareback, tearing back toward the column.

Stanley had heard firing ahead, but a scout had seen buffalo tracks heading in that direction and told him he thought the ruckus was caused by a hunt. Then Stanley heard gunfire much closer, and shortly after Private Brown barreled into sight crying, “All down there are killed!” Stanley sent the rest of the cavalry forward.

Meanwhile, Custer was in a difficult situation. He had been fighting for three hours, and ammunition was beginning to run low. Each man carried one hundred rounds, and they had exhausted most of their supply. Custer did not even know if relief from Stanley was coming. The Indians maintained “a perfect skirmish line throughout,” according to Lieutenant Larned, “evincing for them a very extraordinary control and discipline.”

20

But eventually the Indians' discipline began to break down. The reason became apparent to the cavalrymen as they noticed a huge dust cloud behind the hills to their right, evidence of the relief column. As four squadrons of cavalry galloped into view, it was, George said, “time to mount our steeds and force our enemies to seek safety in flight, or to battle on more even terms.”

21

He ordered his men to mount, then without pause charged the Indians. The warriors broke and fled upriver.

22

By the time the relief column arrived, the battle was over. Custer had won the field and suffered only a few men wounded.

The survey continued, though the loss of the three men to Rain-in-the-Face's scouts encouraged tighter security. On August 8, the expedition came across the recently abandoned site of Sitting Bull's village, and Stanley ordered Custer and 450 men to give chase. They

tracked the Indians swiftly up the north bank of the river, and two days later reached a point three miles below the mouth of the Bighorn where the Indians had crossed. Custer attempted to make the south bank but the Yellowstone was too deep and swift.

The next day, “the river had fallen considerably and preparations were being made to cross over,” Edward S. Godfrey wrote, “when a number of shots were fired from the woods on the opposite bank, and soon after the Indians appeared in force.”

23

At first light, friendly Indian scouts came “tumbling down the bluffs head over heels, screeching, âHeap Indian come.'” Hundreds of warriors appeared along the bluffs above the south bank of the river, firing at the cavalrymen, who returned fire with enthusiasm. Second Lieutenant Charles Braden was seriously wounded repelling a rush from a group of Indians who closed to within thirty yards of his position. This back-and-forth went on for some time, and while Custer's men were occupied, three hundred Indians crossed the river above and below their position, a tactic Sitting Bull had used against the surveying party the previous year. The Indians rushed to the high bluffs six hundred yards to Custer's rear and began to open fire.

The 7th was caught in a crossfire. Custer had a horse shot out from under himâthe eleventh of his careerâand his orderly, Private John H. Tuttle of Company E, who had been boldly standing in the open showing off his considerable skill as a sharpshooter, was killed. But Custer had been in tougher scrapes than this. He pushed a picket line toward the Indians to his rear, then ordered a charge.

“George sat on his horse out in advance, calmly looking the Indians over,” Thomas Rosser wrote of the scene, “full of suppressed excitement, but also with calculating judgment and strength of purpose in his face . . . I thought him then one of the finest specimens of a soldier I had ever seen.”

24

The sudden charge broke the Indian position, and the cavalry pursued them for three miles. Meanwhile, the main column had come up. Stanley ordered artillery fire placed on the ridgeline where the

Indians had congregated across the river, “producing a wonderful scampering out of sight,” he wrote.

25

In the engagements on the Yellowstone, the Indians were armed with new, advanced weapons, and had adapted to them with fresh tactics. But Custer's takeaway was that disciplined and well-organized cavalrymen employing coordinated firepower could hold their own against, and even defeat, superior numbers of Indians. “The Indians were made up of different bands of Sioux, principally Uncpapas,” Custer wrote in his after-action report, “the whole under command of âSitting Bull,' who participated in the second day's fight, and who for once has been taught a lesson he will not soon forget.”

26

A newspaper reporter who witnessed the battle concurred, saying the fights “will have an excellent moral effect upon them and teach them a lesson of our summary management in case of their hostility.”

27

Stanley was more circumspect. “The loss of the Indians in these two affairs was considerable,” he wrote, but “they are not badly enough hurt to be humble.”

28

Reaching Pompey's Pillar soon after the August 11 battle, the column went north to the Musselshell River, down the valley to the Big Bend, then divided. The 7th Cavalry headed back to Fort Lincoln directly, and Stanley with the rest of the expedition went south, going via the Yellowstone. Custer and his men arrived a day before Stanley, who had taken the steamer

Josephine

while the rest of his column went overland. The unexpected and early arrival of the 7th Cavalry became a general topic of conversation. “How did he come?” “Marched of course.” “But that isn't possible.” “Nonsense, nothing is impossible with Custer.” The

Bismarck Tribune

hailed Custer as “a man in whom sloth took no delight, and as an officer the hero of more rapid marches and harder fights than almost any other noted in history.”

29

The Yellowstone expedition lasted 95 days, made 77 encampments, and covered 935 miles. It surveyed previously unmapped areas and found a number of possible railroad routes. The 7th Cavalry engaged

the Indians, and Custer won his battles. He also brought back some bob-tailed cats, porcupines, antelope horns, and petrified wood to send to the Central Park Zoo.

But on September 18, 1873, a week before the expedition ended, the Cooke and Company investment bank, which had underwritten the Northern Pacific, went bankrupt. Cooke's firm had gone into enormous debt, and the tight money policy of the Grant administration dried up the bond market, driving away potential investors. The Northern Pacific could not support its obligations, and even Cooke was not too big to fail. His downfall led to other banks, railroads, and businesses going bust, precipitating the Panic of 1873. The economic hard times lasted in the United States for six years, and the main line of the Northern Pacific was not completed until 1883.

A year later, scout Charley Reynolds attended an Indian war dance, where he learned from “some educated half breeds” that a young warrior named Rain-in-the-Face was bragging that he had killed two civilian members of the Yellowstone expedition with his bare hands. Reynolds got word to Custer, who ordered his brother Tom and a squadron of cavalry to “arrest the red braggart and bring him to Fort Lincoln.”

30

Tom found Rain-in-the-Face at the Standing Rock Reservation on December 13, 1874, and took him in, with some difficulty. The warrior was held at the guardhouse at Fort Lincoln until April 1875, when he escaped. Rain-in-the-Face made his way back to his people, vowing to cut out Tom Custer's heart and eat it.

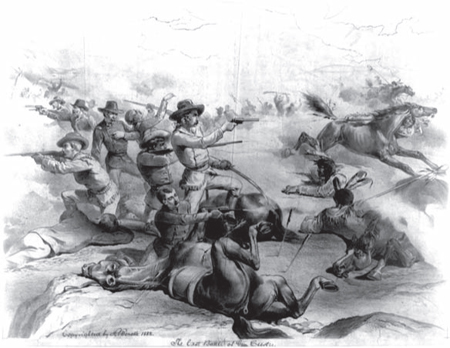

Herman Bencke,

The Last Battle of Gen. Custer

.