The Real History of the End of the World (19 page)

Read The Real History of the End of the World Online

Authors: Sharan Newman

BOOK: The Real History of the End of the World

9.5Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

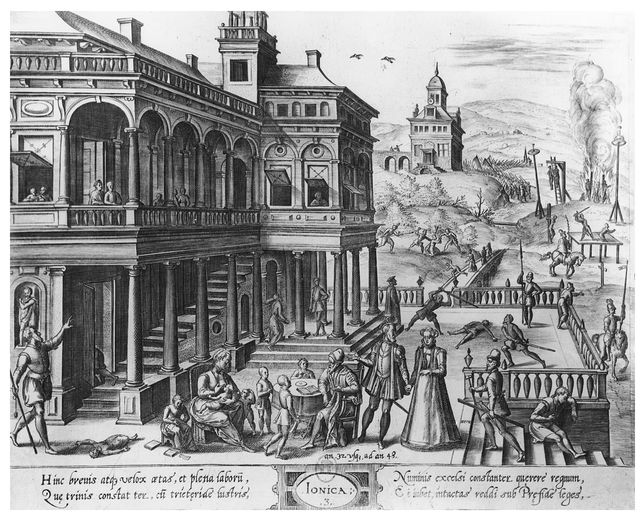

Catherine de Medici consulting Nostradamus to learn her children's fate. 17th CE Location: Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, France.

Snark/Art Resource, NY

Snark/Art Resource, NY

Nostradamus has never completely lost his popularity. He has been credited with predicting the French Revolution, the rise of Napoleon and Hitler, and the fall of the Twin Towers in New York City. I think this may be due to the vague nature of the quatrains. When something happens, it's not difficult to find one that can be twisted to suit the event.

In order to get into the spirit of interpreting the prophecies, I picked one at random from the almanacs. This is from October 1555.

Venus Neptune poursuiura l'entreprise,

Serrez pensifs, trouble les opposans

Classe en Adrie, citez vers la Tamise

Le quart bruit blesse de nuict de reposans.

26

Serrez pensifs, trouble les opposans

Classe en Adrie, citez vers la Tamise

Le quart bruit blesse de nuict de reposans.

26

Now, this is not all that clear for several reasons. For one thing, words are left out. The first line is: “Venus Neptune will pursue the undertaking.” That might be astrological, saying that Venus and Neptune will give one success, but the verb is singular, so it might be that Venus Neptune is someone's name, and the reader should go to her for a loan. The next line is: “You will be thoughtful (masculine) trouble the opponents.” But here

trouble

isn't a verb. So, either there is a verb missing or

serrez

is meant to go with trouble, except then it should be troubler. But, if it is, there is still a problem because a preposition is also missing. Will you be trouble to the opponents or will they be trouble to you?

trouble

isn't a verb. So, either there is a verb missing or

serrez

is meant to go with trouble, except then it should be troubler. But, if it is, there is still a problem because a preposition is also missing. Will you be trouble to the opponents or will they be trouble to you?

You can see the usefulness of vagueness to a prophet.

The next line is interesting because it contains words that Nostradamus uses several times, causing debate among later expositors. “

Classe en Adrie.

” I read this as “A tumult in Adrie.”

Classe

has been translated as a Greek or Latin word by some Nostradamus enthusiasts, but it's perfectly good Old French and means “tumult” or “trumpet blast,” which could be a tumult as well or even a “trumpet blast to call the people together.”

27

Adrie

is a bit trickier. It could well be “Adriatic” or “Hadrian.” But the rest of the line is “a city near the Thames,” so I'm guessing that he was thinking of England, France's long-time enemy. Some have decided that it means Hadrian, who is Adolph Hitler, of course (?). You decide.

Classe en Adrie.

” I read this as “A tumult in Adrie.”

Classe

has been translated as a Greek or Latin word by some Nostradamus enthusiasts, but it's perfectly good Old French and means “tumult” or “trumpet blast,” which could be a tumult as well or even a “trumpet blast to call the people together.”

27

Adrie

is a bit trickier. It could well be “Adriatic” or “Hadrian.” But the rest of the line is “a city near the Thames,” so I'm guessing that he was thinking of England, France's long-time enemy. Some have decided that it means Hadrian, who is Adolph Hitler, of course (?). You decide.

The fourth line seems to complement the one before it. “The quarter noise wounds the night of the sleeping ones.” So everyone is wakened by a tumult or trumpet or warning siren in the night. Say! I'll bet it refers to the Blitz in World War II. Or the Zeppelins in World War I, or the bombers over Baghdad, or maybe it's a warning of an attack to come. I think I'm catching on to this interpretation thing!

Or it could just mean that people will be startled by a sound in the night. It's a pretty safe bet that this will happen at some point in history.

I think it's fun try to find a meaning in mysterious verses, especially if it means wordplay in several languages, but I don't get out much.

The real question is, did Nostradamus predict the end of the world?

Yes.

And sort of.

In the preface to his first century, Nostradamus tells his son that the work “comprises prophesies from today to the year 3797.”

28

Well, that's a relief. However, just a few paragraphs later, he says that the end will come in 1999, at the end of a war that will begin in 1975. He repeats the former date in Century 10, Quatrain 72:

28

Well, that's a relief. However, just a few paragraphs later, he says that the end will come in 1999, at the end of a war that will begin in 1975. He repeats the former date in Century 10, Quatrain 72:

L'an mil neuf cens nonante neuf sept mois,

Du ciel viendra un grand Roy d'effrayeur:

Resusciter le grand Roy d'Angolmois,

Avant apres Mars regner par bon heur.

Du ciel viendra un grand Roy d'effrayeur:

Resusciter le grand Roy d'Angolmois,

Avant apres Mars regner par bon heur.

Â

The year one thousand nine hundred nine seven months,

A great king of terror will come from the sky:

To revive the great king of the Angols,*

Before after Mars to reign through luck (or happiness).

A great king of terror will come from the sky:

To revive the great king of the Angols,*

Before after Mars to reign through luck (or happiness).

There has been a lot of debate about the word

Angolmois.

In Nostradamus's time it probably meant the people of Angola, which was known through trade. Some have suggested that it is a sort of pig-Latin for Mongols “Angol-mois.” I have no idea what Nostradamus had in mind, but he does seem to indicate a great upheaval of some sort in 1999.

Angolmois.

In Nostradamus's time it probably meant the people of Angola, which was known through trade. Some have suggested that it is a sort of pig-Latin for Mongols “Angol-mois.” I have no idea what Nostradamus had in mind, but he does seem to indicate a great upheaval of some sort in 1999.

So, according to Nostradamus, we either have over a thousand years to the end or it already happened and no one noticed.

But nowhere in the quatrains is there even a hint that Nostradamus thought the world would end in 2012.

1

My translation.

My translation.

3

This biography is based on the work of Edgar Leroy in 1972. This book is almost impossible to find, showing that accuracy is not always rewarded. I have compiled this from quotes of his work in other sources. Not my favorite way of doing research.

This biography is based on the work of Edgar Leroy in 1972. This book is almost impossible to find, showing that accuracy is not always rewarded. I have compiled this from quotes of his work in other sources. Not my favorite way of doing research.

4

Another, secondary source, says that his name was Abraham Solomon. Cf. Adolf Kober, “Jewish Converts in Provence from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century,”

Jewish Social Studies

6, no. 4 (1944): 363. Kober cited general histories of Provence that are not completely reliable. To my mind, “Abraham Solomon” is such a stereotypical name that I'm inclined to doubt it. It is also the name of a court physician for King René of France in 1445, far too early to have been Michel's grandfather.

Another, secondary source, says that his name was Abraham Solomon. Cf. Adolf Kober, “Jewish Converts in Provence from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century,”

Jewish Social Studies

6, no. 4 (1944): 363. Kober cited general histories of Provence that are not completely reliable. To my mind, “Abraham Solomon” is such a stereotypical name that I'm inclined to doubt it. It is also the name of a court physician for King René of France in 1445, far too early to have been Michel's grandfather.

6

Salo Baron,

A Social and Religious History of the Jews,

vol. IV (New York: Columbia University Press, 1960), 45-48.

Salo Baron,

A Social and Religious History of the Jews,

vol. IV (New York: Columbia University Press, 1960), 45-48.

7

Kober, 365.

Kober, 365.

8

Wilson, 5-7. I would like to point out that knowing one's great-grandfather was only as unusual then as it is now.

Wilson, 5-7. I would like to point out that knowing one's great-grandfather was only as unusual then as it is now.

9

Nostradamus,

Traité de fardemens et confitures

(Lyon, 1555). I'm surprised that no one has come out with a Nostradamus cookbook.

Nostradamus,

Traité de fardemens et confitures

(Lyon, 1555). I'm surprised that no one has come out with a Nostradamus cookbook.

10

This is listed in several sources as being on record at the university.

This is listed in several sources as being on record at the university.

11

Vernon Hall Jr., “Life of Julius Caesar Scaliger (1484-1558),”

Transactions of the American Philosophical Society

new ser. 40, no. 2 (1950): 117-118. Hall spent five years studying the Scaliger family papers that had never been examined before, certainly not by those interested in Nostradamus.

Vernon Hall Jr., “Life of Julius Caesar Scaliger (1484-1558),”

Transactions of the American Philosophical Society

new ser. 40, no. 2 (1950): 117-118. Hall spent five years studying the Scaliger family papers that had never been examined before, certainly not by those interested in Nostradamus.

12

Ibid., 118.

Ibid., 118.

13

Ibid. Hall cites the records of the Inquisition, still in existence (the records, not the Inquisition).

Ibid. Hall cites the records of the Inquisition, still in existence (the records, not the Inquisition).

14

Ibid. Again from the records of the Inquisition.

Ibid. Again from the records of the Inquisition.

15

Ward, 6.

Ward, 6.

16

Wilson, 237-238

Wilson, 237-238

19

Ward.

Ward.

20

Hall, 129.

Hall, 129.

21

Wilson, 106.

Wilson, 106.

24

Ibid., 66.

Ibid., 66.

25

Wilson, 255.

Wilson, 255.

26

Hutin, 337.

Hutin, 337.

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

Sabbatai Sevi

Almost the Messiah

Â

A Girl from Galata . . . told her parents that an angel hadrevealed himself to her, holding in his hand a flaming sword.

And that he had told her that the true Messiah had come and

that very soon he would appear on the banks of the Jordan.

âFriar Michel Févre, on Sabbatai Sevi

1

1

Â

Â

Â

Â

I

t was not only European Protestants who saw the seventeenth century as the beginning of the millennium, Jews in eastern Europe and the Ottoman Empire were also on a heightened watch for the coming of the Messiah. Perhaps the growth of the Protestant movement encouraged them to feel the world was ripe for change. Across the East there was much discussion about possible signs that the Messiah would appear any moment. And one man managed to convince thousands of both Jews and Christians that he was the real thing.

t was not only European Protestants who saw the seventeenth century as the beginning of the millennium, Jews in eastern Europe and the Ottoman Empire were also on a heightened watch for the coming of the Messiah. Perhaps the growth of the Protestant movement encouraged them to feel the world was ripe for change. Across the East there was much discussion about possible signs that the Messiah would appear any moment. And one man managed to convince thousands of both Jews and Christians that he was the real thing.

Sabbatai Sevi

2

was born in the Ottoman town of Smyrna, now Izmir, Turkey, in 1626, the son of a merchant. Sevi spent his youth in the study of the Talmud before moving on to the Zohar and other kabbalist writings.

3

He apparently had ecstatic visions from young adulthood and, in 1648, announced to a few close friends that he had had a dream that told him that he was the Messiah. In 1651, he was expelled from Smyrna for making this public and so made his way to Gaza. There he met another Kabbalah scholar, Nathan Ashkenazi.

4

2

was born in the Ottoman town of Smyrna, now Izmir, Turkey, in 1626, the son of a merchant. Sevi spent his youth in the study of the Talmud before moving on to the Zohar and other kabbalist writings.

3

He apparently had ecstatic visions from young adulthood and, in 1648, announced to a few close friends that he had had a dream that told him that he was the Messiah. In 1651, he was expelled from Smyrna for making this public and so made his way to Gaza. There he met another Kabbalah scholar, Nathan Ashkenazi.

4

In 1665, Nathan “fell into a trance” during a synagogue service. When he came out of it, he informed his colleagues that he had been told that Sabbatai Sevi was indeed the Messiah and that Nathan had been chosen to be his prophet.

5

5

At the beginning, the two men and their few converts made little attempt to proselytize. However, using the network established by Jewish traders and travelers, word of their message soon spread throughout Jewish communities under both Islamic and Christian rule. The news of the Messiah's appearance went as far as England, Russia, Morocco, and Yemen. Sevi's father was the agent for several English Christian merchants who were also millenarians, and they took the story back with them.

6

To them this was the first sign of the approach of Armageddon.

6

To them this was the first sign of the approach of Armageddon.

The farther the rumors reached, the more they expanded.

Nathan tried to stem the rising tide of stories concerning the fantastic miracles performed by Sabbatai Sevi, stating that believers should accept Sevi as the Messiah without miracles. “[The Messiah] reaches the understanding of the greatness of God, for this is the quintessence of the Messiah. And if he does not do so then he is not the Messiah. Even he displays all the signs and wonders in the world, God forbid that one should believe in him, for he is a prophet in idolatry.”

7

7

Sabbatai Sevi finally began to travel, preaching his beliefs. It's not clear how many paid attention to him or understood his mystical ideology. He and his followers visited the Jewish communities of Cairo in 1662, where he was welcomed by the leader of the Cairo community and the chief rabbi of Alexandria, Hosea Nantawa. The community provided funds and sent word of their support to the Jews of Italy.

8

With very little proselytizing on his part, the self-proclaimed Messiah was rapidly gathering an international following.

8

With very little proselytizing on his part, the self-proclaimed Messiah was rapidly gathering an international following.

Despite Nathan's insistence that miracles don't make a messiah, stories of the wonders performed by Sabbatai Sevi spread across the Diaspora. Some said that the lost tribes of Israel had returned and were marching across the desert. Others that Sabbatai Sevi had caused Christian churches to sink into the earth and had walked through fire without being burned.

9

The excitement was not contained within the Jewish communities. One English Puritan pamphlet reported that a ship had washed ashore in Scotland bearing the banner “These Are of the Ten Tribes of Israel.”

10

9

The excitement was not contained within the Jewish communities. One English Puritan pamphlet reported that a ship had washed ashore in Scotland bearing the banner “These Are of the Ten Tribes of Israel.”

10

Despite Nathan's mystical explanations of the nature of Sevi as the Messiah, followers insisted on physical evidence of the validity of his role. How many of the stories of his cures and power over nature actually came from the Sabbateans is uncertain, but it does seem that they totally overshadowed the reality.

Christian millenarian hopes were kindled through reports that Sevi and Nathan were leading an army of Jews across the desert. Papers in the Netherlands and Germany reported almost daily on the progress of this phantom army, and these stories were picked up as far away as Muscovy, where it was stated that Mecca had been taken, and the Prophet's tomb had been looted.

11

In England, many felt that this was a sign that the Jews would retake Jerusalem, a belief that encouraged the remnant of Fifth Monarchists remaining under the Restoration.

12

11

In England, many felt that this was a sign that the Jews would retake Jerusalem, a belief that encouraged the remnant of Fifth Monarchists remaining under the Restoration.

12

Eventually, Sabbatai Sevi and his followers returned to Smyrna, where, in 1665, he seems to have accepted the public duties of his position. The Messiah was foretold to be a political leader who would lead armies. He and his disciples began by taking over Smyrna. Sevi then divided the world into regions and named several of his supporters as kings.

13

13

Other books

Gentling the Cowboy by Ruth Cardello

Faithless by Bennett, Amanda

The Path of Minor Planets: A Novel by Greer, Andrew Sean

Taming Naia by Natasha Knight

The Wedding Wager (McMaster the Disaster) by Astor, Rachel

The Zen Man by Colleen Collins

Till the End of Tom by Gillian Roberts

Shieldwolf Dawning by Selena Nemorin

Refund by Karen E. Bender

The Next President by Flynn, Joseph