The Real Life Downton Abbey (26 page)

Read The Real Life Downton Abbey Online

Authors: Jacky Hyams

The total cost of a new female servant’s working uniform can frequently add up to as much as £3 or £4, representing several months’ wages for a scullery maid. So if a new maid cannot manage to borrow from friends or family to gradually repay from her wages, the housekeeper may agree, via the mistress, that they fork out for her uniform – and deduct the cost from her pay. Hair, too, must be neat and unobtrusive: a 15-year-old housemaid with her hair severely drawn back, braided and neatly pinned usually looks much older than her years.

Of the female upper servants, the housekeeper usually wears dark, somewhat sombre and severe plain dresses, usually black with a white frill at the collar and a white lace cap. Governesses wear similar attire. Only the lady’s maid is permitted to be remotely fashionably dressed, given the need for her to be

up-to

-date to advise her boss on the latest trends and looks. Yet she too, at interview stage, might be subjected to certain restrictions in her appearance by the housekeeper. She could be asked to remove the hidden ‘rats’ or pads from beneath her swept-up hairdo. Or she might be told to cut the tail off a fashionable long dress. She has to look appropriate for the lady – and the household – she works for.

In many cases, the lady’s maid does not have much money to spend if she’s saving up for her time off and visits to her family. So she frequently wears cast-offs, excellent quality clothes given to her by her employer (or previous employers), which she can, with the help of the sewing machine, alter to suit her shape. And, of course, while she must look good to reflect her boss’s status, she can only look modestly fashionable and well turned out. Nothing too extravagant.

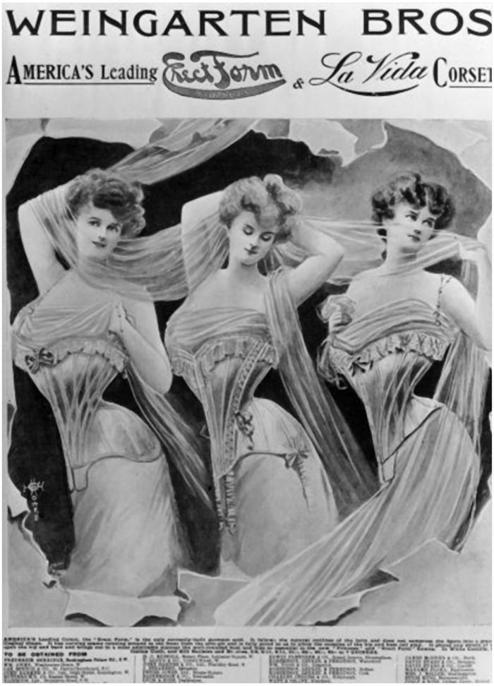

Tightly laced corsets are worn by all women. For a young servant this can be even more uncomfortable and constricting than the corset worn by her mistress: wealthy women’s corsets have whalebone stays (supports) which are more pliant – yet poorer people’s stays are made from cheaper metal. So the corsets, worn over a cotton vest and cotton bloomers, really dig into the girls’ hips and stomach, let alone the discomfort of the tight waist lacing which can even make eating difficult. Given the amount of bending, stretching and kneeling the housemaids are doing as part of their everyday routine, it must have been tempting to give the corset a miss sometimes. Yet until the less restrictive underwear comes in towards the close of the Edwardian era, they must put up with it.

Boots are an expensive item for servants to buy: one new pair of handmade boots can cost around £2. In the nineteenth century when live-in servants are paid annually, payday means a trip to the local village to pay their annual account with the shoemaker, and on settling day the shoemaker celebrates – by providing a dish of stuffed chine (salt pork filled with herbs) for his customers.

From her early dressmaking beginnings making clothes for friends, Lucy Christiana Sutherland, known professionally as ‘Lucile’, a divorced woman with a small daughter, rises to prominence – via a society marriage to Scottish landowner and sportsman, Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon in 1900 – as the most important fashion designer in the country, designing exclusive, romantic, feminine and sensual lingerie, tea gowns and evening wear for royalty and the fashionable elite. (She is also the sister of acclaimed Edwardian novelist Elinor Glyn.)

Lucile is the first designer to give her clothes names, such as ‘Do you Love me?’ or ‘When Passion’s Thrall is O’er’, and is an innovator of early ‘catwalk’ fashion shows in her plush, carpeted Hanover Square showroom where her gowns, exquisitely feminine creations of beaded and sequined embroidery, with lace inserts and garlands of tiny roses, are paraded by statuesque beauties before their elegant audience.

THE MULTI-PURPOSE CLAYThe Lucile brand is expanded to New York in 1910 and Paris in 1911. She and her husband are also survivors of the ill-fated

Titanic

voyage in 1912; afterwards, rumours persist for many years that Cosmo bribed the crewmen in their lifeboat not to return to the sinking ship to rescue others. After World War I, when fashions change, Lucile becomes a fashion columnist and pundit until her death in 1935.

SHOPPING FOR PLEASUREFuller’s Earth is a highly absorbent clay, rich in minerals, used for a wide range of purposes including stain removal, as a skin cleanser, to help clear up spots or nappy rash and also as a dry shampoo. Mixed with water, Fuller’s Earth powder makes a natural face pack to help remove blackheads and skin impurities. It can also give relief from insect bites when mixed with water and apple cider vinegar.

The growth of conspicuous consumption is significant in the Edwardian era. Shopping as a leisure activity, originally a Victorian innovation, now expands even further, thanks to greater transport facilities and the rise of the comfortably-off middle classes. Harrods in Knightsbridge is a huge draw for the elegant and wealthy as is Selfridges, whose opening in Oxford Street in 1909 draws five million people in its first five days.

RATIONAL DRESS SOCIETYFashionable shopping hours are between 2pm and 4pm and these upmarket stores have their own extensive workrooms employing hundreds of women hand-sewing exclusive made-to-measure garments for wealthy women, frequently offering copies of Paris models. If she can’t find time to get away, a country-house lady can also now order her clothes from a mail-order catalogue from big department stores, outfits which might consist of a

ready-made

skirt and material for the bodice or top, to be made up by the lady’s maid. And aspirational middle-class women are also flocking to the other big, smart department stores in London, Edinburgh, Birmingham and Manchester. Many of these stores, like Fortnum & Mason (who started out as grocers in 1707) grow out of small specialist shops. Harrods starts life as a grocery store in 1849, and Thomas Burberry, originally a country draper, opens in London in 1904, creating clothes for the female motorist needing a special motoring coat to protect against dust and weather. Clothing brands like Jaeger start out as a ‘scientific’ idea promoting wool fibres for clothing, particularly underwear. This too evolves, as a number of retail stores selling men’s and women’s clothes made from fine natural fabrics start to open everywhere.

LIVERY & POWDERED HAIRFounded by Viscountess Harberton in 1880, to promote healthier fashions that do not restrict or deform the body, the society is against the wearing of tight corsets,

high-heeled

shoes, heavily weighted skirts and all garments impending free movement of the arms and legs. The organisation also believes that no woman should wear more than 7lb of underwear (back then, underwear was made of bulky gathered cotton and heavy wool flannel). By 1895, a few privileged women are starting to appear in rational dress consisting of loose divided skirts for biking and more tailored suits for daywear. But it’s not until much later, after World War I, that fashions really start to become easier to wear and more comfortable for everyone.

Livery, a traditional and very distinctive colourful servants’ outfit for men, has been worn by country-house footmen for centuries. And by the start of the twentieth century, some country-house families still require their footmen to wear livery at certain times during the day, while others prefer footmen to wear livery just for specific events, like balls or big receptions. So footmen in country houses where livery is worn at certain meals find themselves spending a great deal of time dressing and undressing. For example, they serve lunch in an outfit consisting of black trousers, waistcoat, white shirt, white bow-tie and knee-length boots. Yet when serving tea and dinner they change into scarlet livery consisting of a short scarlet coat, a scarlet waistcoat, purple knee breeches, white stockings, black pumps with bows and a square white bow-tie. (Staff sometimes buy ready-made bow-ties with a round collar, to save dressing time.)

In many aristocratic London town houses, large supplies of livery are kept in the house, only to be worn by footmen at big balls or entertainments, complete with top hats. And in a few big houses, footmen in livery are still required to have powdered hair, a hangover from the eighteenth century, when many senior servants of both sexes wore grey wigs. As well as providing the livery for footmen, some country-house owners provide the powder – or the money to buy it. Powdering hair is a lengthy process. Hair must be wet, then soap is rubbed in to produce a stiff lather so the lather can be combed through. Finally a powder puff is used liberally all over the head and left to dry until firm. Later, at night, the hair is washed and oiled to remove the powder.

A poster advertising the Weingarten Brothers’ La Vida Corset.

Chapter 12

H

ow healthy are the people living in the country house? Food-wise, at least, both toffs and servants are much better off than the rest of the population. The daily diet consists of fresh, plentiful food, grown or produced on the estate. So valued is this home-grown produce, wealthy families often have some foodstuffs transported, by train, to their London town house during the Season. Yet overindulgence is such a feature of the toffs’ world, because there is so much emphasis on meals and entertaining. Balanced against that, of course, there’s the country-house outdoor lifestyle, the shooting, riding, hunting, tennis and cycling.

The servants’ food may not be lavish, but it’s still much better than the diet of most working-class people. Mostly, those in service walk on Sundays and time off – or use a bike, so their lifestyle isn’t completely unhealthy.

There’s much greater emphasis now on outdoor activity and sport. Edwardians have thrown off the stuffy, cluttered claustrophobic environment of the Victorians. The middle classes especially, are very keen on fresh air, getting out and about, playing sport and taking more exercise, especially women, now that they’re beginning to be less restricted by clothing. The introduction of electric lighting in the cities makes getting around after dark less dangerous too.

Yet the reality is, health wise, the overall population, especially children, are no healthier now than they were half a century ago. Poverty is one big reason for this. For the majority, life is grim: there are large slum areas, shockingly overcrowded. But another reason for the lack of improvement in the nation’s health is down to ignorance: nutrition, so crucial to development and wellbeing, is poorly understood by many.

The toffs are happy to make their annual visits to fashionable spa resorts and take some sort of ‘cure’ as a penance for their overindulgence. But they’re not swallowing vitamin tablets and making carrot juice in the blender the rest of the time. The multi-course Edwardian diet is rich and unhealthy, with very large amounts of meat and considerable quantities of all manner of alcoholic drinks, plus many sugary or starchy treats on the table. So the posh digestive systems take a terrible caning. Yet they are mostly quite careless of the consequences of all this. After years of overindulging at the table, many have stomach or digestive illnesses like indigestion, gout or gallstones. Overindulgence in alcohol and smoking too – all those smoke-filled Gentlemen’s Clubs and ordinary pubs – are not considered injurious to health by most. Alcoholic excess is taken seriously by the do-gooders and middle classes as a social problem of the less fortunate – the servants definitely can’t be seen to be tipsy in the dining room – but the concern doesn’t go beyond that.

Yet the aristos’ close involvement with the politics of the time mean that some retain genuine concerns for the social welfare of their tenants and the poor. Part of their remit involves helping fund-raise or donate to local institutions like cottage hospitals, or sitting on the boards of larger teaching hospitals. But for the most part their own health, as far as their culinary excesses are concerned, does not come under too much scrutiny. However, dieting fads are now starting to surface, with US dieting gurus like Horace Fletcher getting considerable attention from the smarter sections of society.

Medicine is starting to improve. There are no antibiotics to treat bacterial infection yet (the first commercially produced antibiotics are not available until World War II), and vaccinations against killer illnesses like measles don’t appear until the early sixties. Diphtheria and tuberculosis are still rife, accounting for many childhood deaths. (While vaccination for smallpox, cholera and typhoid fever are already available by the early 1900s, the first vaccines for diphtheria and tuberculosis don’t arrive until the 1920s.) Nor have important social

health-related

issues like birth control or the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases been tackled.