The Real Mad Men (24 page)

Authors: Andrew Cracknell

A campaign for Eastern Airlines, “The Wings of Man,” created by Steve Frankfurt at Young & Rubicam. This advertisement was on the author's office wall in London in the late 1960s.

Harper joined McCann-Erickson, a large New York agency, in 1939 at the age of twenty-three as a trainee. Nine years later he was the president. That his trajectory through the ranks of what was a very conservative company was so rapid came as no surprise to those who knew of his phenomenal work ethic, focus, and intellect.

Born in Oklahama in 1916, his precocity was quickly obvious. At the age of ten he was addressing the United Daughters of the Confederacy in the Oklahoma State Capitol on his chosen subject, “The Time is Here for the North and South to Forget their Differences and Pull Together.” His mother, an occasional newspaper columnist who was both politically and socially aware, brought him up after his father, a newspaper space salesman, had left the family and moved to New York.

Harper worked diligently at school and after two years at Andover went to Yale, leaving in 1938 with top honors in math, economics, and psychology. His father, by then a vice president of General Foods, was an early believer in marketing and distribution research. It was a leaning that rubbed off on Marion; he'd worked his summer vacations as a door-to-door salesman, mainly of women's goods, experimenting on the relative effectiveness of different sales pitches.

The following year he started in the postroom at McCann Erickson at 285 Madison Avenue. Hanging around the research department and asking endless questions laced with a few ideas of his own quickly got him promoted, and he was given his own research project to oversee, a method of testing ad copy prior to publication. He was mind-numbingly diligent in his analysis and by the age of twenty-six he was head of copy research, by thirty director of research, and by thirty-two, in 1948, president of McCann-Erickson.

By now he was married, with two children, not that he saw much of themâthe next decade was outstanding for McCann and there's no question that it was the result of Harper's indefatigable effort. From fifth place in terms of agency size, with billings of $50 million, the company had a period of growth matched only by BBDO; by 1959 McCann Erickson was second only to JWT in size, billing $231 million.

He was personally quiet, “actually shy, a lonesome man, the company was his life,” says Carl Spielvogel, an executive who worked closely with him from 1960. But Harper's moves were bold and unconventional. In

1958, in an almost unprecedented act, he resigned the Chrysler account for the smaller Buick business, believing that being on the GM roster represented the better opportunity for his agency's growth. It wasn't a popular move, but Harper's judgement proved to be right.

He was careful, too, to nourish McCann's already advanced global reach. Again, it was only JWT that could better McCann's international client roster by 1960. One gain in particular was Coca-Cola, which became a flagship business for the agency. The agency won the account precisely because Coca Cola's incumbent agency, D'Arcy, had shown no great enthusiasm to offer the overseas services that Coca-Cola needed and subsequently found at the vigorously global McCann.

In the business of the industry, Harper always seems to have been several steps ahead of everyone else. “He was a brilliant conceptualist. He could formulate ideas that took the industry quite a while to catch up with” says Spielvogel. He had a fearsome intellect, a ferocious work ethic, frequently putting in twenty-four-hour stretches, and phenomenal concentration. He would regularly astonish colleagues in new business presentations by displaying a detailed knowledge of the minutiae of, say, the prospective client's regional market share or pricing policy, even though he'd been handed the fat briefing documents only two hours before the meeting.

TALL, BALD, AND HEAVY SET

, this focus did not make Harper approachable, although it gained him respect; in a 1963

Time

magazine article, an unnamed agency president said, “While I find Marion unattractively impersonal and ruthless, he does seem to be a marvelous organizer, and his mental capacity is immense.”

His capacity for innovative thinking was unending. Most of it seemed to come from a mind obsessed with research, especially with finding out what made things work and then implementing improved versions of them. He also had the ability to rise way above the daily grind; whilst being super-diligent about detail he would also be first with what we now call a “helicopter view.”

A lot of McCann's appeal to clients was based around new and seductive research tools, encouraged by Harper. They were attracted to techniques with reassuringly technical names, such as the Relative Sales Conviction

Test, which apparently guaranteed advertising success. How could you fail if your ads had been tested, for example, in The Perception Laboratory? This was a concept shown to him by a Dr. Eckhart Hess at the University of Chicago, which he adapted and modified to analyze responses to advertising by measuring the pupil dilation of interviewees while being shown various visual stimuli.

He was a seer; he is credited with being the first person to coin the term “think tank.” He was the first to describe the wider function of an ad agency as “marketing communications.” thirty years before the phrase became common usage. He arrived at the term partly because he was one of the first people to urge his staff to think beyond advertising on behalf of their clients. As early as 1960 he was talking about “holistic” answers to marketing problems (another industry buzzword thirty years later). He was enthusing about the coming “information explosion” and he had a prescient interest in computers. Many of these ideas came from the Institute of Communications Research, a McCann think tank to shape all the other think tanks, a department to improve the agency's primary functions.

One notion, typical of the extraordinary breadth of his imagination and his fascination for the concept of the group thinkingâtogether with his talent for packaging his ideasâwas best described by Russ Johnston in his book,

Marion Harper: An Unauthorized Biography

, a riveting account of this intriguing man and his unusual story:

“He called it âThe Humanivac' a combination obviously of âHuman' and âUnivac,' as the then most popular computer was known. His idea was to assemble people like parts of a giant brain, each specializing in a particular aspect of marketing. A problem would be presented, each part of the human machine would go into action, and in a short time the solution would roll out, neatly packaged and ready to go to market. Some people thought it was fortunate that the idea slowly disappeared. Today [1982] it seems feasible but in 1962 it seemed pretty far-fetched. But, then, so was putting a man on the moon.”

His most obvious and publicly recognized goal was to overtake JWT in size. But a much later remark, talking about his aims at the time he was made president, reveals a much grander vision: “At thirty-eight⦠you can't have as your ambition just to be the best of whatever there already is.” He was always going to do something different and new and the idea that changed not just McCann Erickson but the entire business out of all recognition was so devastatingly simple it seems incredible that advertising could have got so far without anyone having thought of it before. He invented the advertising conglomerate.

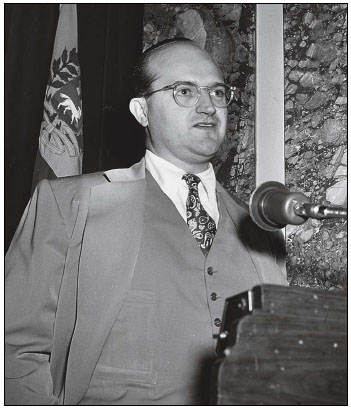

Marion Harper; a brilliant mindâbut flawed.

THE IDEA WAS

driven by clients' deep abhorrence of sharing their advertising agent with any other client who could be conceived as a rival, no matter how remote. They claim it's to preserve confidentiality, but the information passing through an advertising agency can rarely be more sensitive than that passing through auditors, corporate law firms, and banksâcompanies that rival clients are perfectly happy to share. Agencies comply because they have no choice but it means that none can ever handle more than one account in each category; one car, one toothpaste, one airline. (In

Mad Men

Sterling Cooper had to resign Mohawk Airlines to be free to pitch for American Airlines.)

So when one advertising agency acquired another, any conflict would have to be resolved, and usually this meant that the smaller of the conflicting accounts would be resigned. This immediately reduced the value of the merger, with two plus two often making no more than three.

Then Harper, in his words, “turned the management ladder sideways” and started a practice where the acquired agency would operate independently of the acquiring agency, but they would be financially bound by a holding company above them, the beneficiary of their joint profits. Ridiculously simple. But, amazingly, for advertising completely original.

There was a second dimension to the idea, one that has possibly had the greater reverberations through the business ever since. Harper figured that though agencies supplied clients with ancillary services like research, promotions advice and publicity, they never properly charged for them. Because they were located within the agency and were delivered largely by the same team who delivered their advertising, the client perception was that they weren't a separate service and there should not be a significant fee for them.

So his idea was that specialist companiesâMarplan, specializing in market research, Communications Counselors Inc. for publicity, and Sales

Communications Inc. for sales promotionsâshould be set up to provide those services outside the agencies. Initially a number of their staff were actually the people who'd been doing those jobs within the agenciesâno matter, their specific expertise and experience would be properly and separately charged for, and their profits would go to the holding company. Economies of scale would be achieved by having as much common backroom staff to service the agencies and specialist companies as possibleâadministration, purchasing, financeâlocated in the holding company.

The holding company therefore sat on top of a variety of independently operating and competing advertising agencies, each of which could cross-refer business to a variety of equally independent specialist support service companies. Extend this overseas, float it on the stockmarket and you have the prototype of the contemporary marketing services conglomerate like WPP or Omnicom.

Though Harper himself described what he was creating as a “revolution,” it was far from the Creative Revolution over at DDB. Indeed, he had as great a suspicion of it as Bart Cummings, attacking in a major management meeting “the new cult of creativity⦠closely identified with the bizarre.” He was poles apart from Bernbach, whose comment, “I warn you against believing advertising is a science” was in flat contradiction of everything Harper believed. He wasn't neglectful of the creative side but, typically, he viewed it as yet another area that would benefit from the analytical and think-tank-based approachâand he set up yet another Interpublic subsidiary company.

Spielvogel describes it as “a sort of combination of think tank and creative center. It was thinking out how the projects should go creatively, and then turning over the grunt work, the media and development of the creative work, to the agency. Harper called it âco-creativity'âwhat happens when you blend different skills at a very high level. We're conducting an experiment to learn whether through co-creativity you can produce better, neater, brighter, hotter, more creatively.”

It was to be called Jack Tinker & Partners, the partners element indicating that each of the four members (Jack Tinker, an art director; Dr. Herta Herzog, an Austrian psychologist expert in motivational research; Don Calhoun, a copywriter; and Myron McDonald, the marketing director) had an equal voice.