The Real Mad Men (6 page)

Authors: Andrew Cracknell

Never underestimate the power of an eyepatch; one example of the Hathaway campaign.

An Ogilvy campaign? Look againâthese are actually four completely different campaigns for (clockwise from top left) Viyella, Hathaway, British Tourist Board, and Schweppes.

Between 1950 and 1969, Hathaway sales rose from $2 million per year to $30 million; name recognition went from under 1 percent to 40 percent in ten years; and the number of stores stocking the range rose from 450 to 2,500 between 1950 and 1962.

It worked for the agency too, pulling in enquiries from such establishment clients as P&G. So recognizable and so far down the line of OB&M history did the campaign reach that, when Ogilvy's book

Confessions of an Advertising Man

came out in 1965, the publisher's sales force wore eyepatches while selling it in to stores. As an O&M executive apparently said more than thirty years after the campaign first ran, reflecting on its influence on the agency's fame and history, “We'll all have eyepatches on our tombstones.”

THE NEXT MAJOR SUCCESS

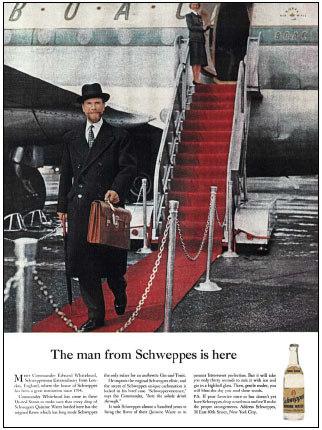

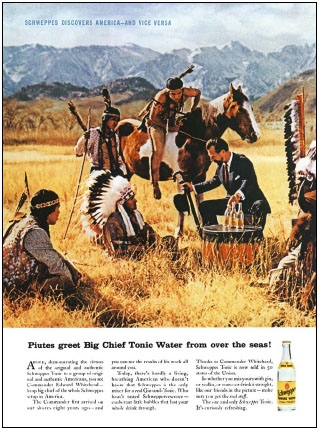

was the tonic water company Schweppes, a tiny piece of business that spent no more than $15,000 on their advertising. Initially, Ogilvy prepared a workmanlike campaign announcing the availability of the tonic water in the New York area, but the client wanted something more exotic. It's unclear who first made the suggestion, but the decision was made to use Commander Edward Whitehead, a former World War II Royal Navy officer who was by that time running Schweppes in the United States.

There was no doubt that he looked the part of a British naval officer; a huge bushy beard under a large-whiskered handlebar moustache gave him a sort of camp King George V look, although what that had to do with selling tonic water is obscure. But no matter; for reasons as impenetrable as the success of the Hathaway Shirt Man, the Schweppes Tonic Man became as big a hit. For eyepatch, substitute beard.

Not that it was all plain sailing with Commander Teddy Whitehead. David Herzbrun, a creative director on the business in 1964, recalls in his book

Playing with Traffic on Madison Avenue

that Whitehead froze in front of the camera. When Harry Hamburg, the photographer, asked for a smile, what he got was “a ghastly rictus of death.” Hamburg muttered to

Herzbrun that the only thing Englishmen of Whitehead's class ever thought was funny was bathroom humor.

“He got Teddy arranged in the right pose, got his camera ready and called out to the Commander, âSay shit!'

“Whitehead said it shyly, with a rather endearing schoolboy smile.

“âLouder,' Harry commanded.

“âShit!' roared Teddy and laughed until the tears came.

“For the next three days Harry shot as Whitehead shat; and the word never failed to produce the desired results.”

As with Hathaway, the media schedule was limited, again majoring on

The New Yorker

but also including

Sports Illustrated

. Although partly driven by the limitation of the budget, it was nevertheless courageous thinkingâfew advertisers back then had the faith to put all their eggs in one basket. But as Whitehead said, he and Ogilvy agreed that “what the discriminating do today, the undiscriminating will do tomorrow.”

It was, as they say, trucks through the night for Schweppes. The public lapped up the images of Commander Whitehead going about his high-octane life, stepping off jet planes, sporting ice on his beard at some chic ski resort, dining with a beautiful woman at a stylish restaurant. Sales were up from under a million bottles to 32 million per year in five years, a remarkable result since it had barely been heard of in the United States before.

OGILVY WAS

, if not exactly a snob, certainly class conscious. As he rather characteristically put it, “There are very few products that do not benefit from being given a first-class ticket through life.” Maybe it was the often experienced reaction of the Englishman of that era in New York, where in the face of the brash, loud, busy new world he retreats into a caricature of his real self and becomes even more English, brittle, and refined. It is not hostility to the surroundings, but perhaps it is to preserve the independence and objectivity of the view that first so captivated him.

He was also capable of the most breathtaking vanity, happy to be quoted by Ken Roman in such conceits as “By twenty-five I was brilliant,” “I lit a candle which is still burning forty years later,” and “I love reading in the press what a great copywriter I am.” Ken also recalls one of the most inventive pieces of Ogilvy's self-aggrandisement, a feature that appeared on the front of the OB&M in-house magazine. With a picture of himself next to one of Charlemagne to prove the physical likeness, Ogilvy proclaimed he'd finally found proof that “your Chairman” is indeed descended from this greatest of legendary medieval kings.

A genuine client with a genuine beard. Commander Whitehead of Schweppes.

At the recollection Roman smiles and says, “It was not a joke. It was serious. But we all kind of smiled, âthat's David being David.' He was a man of enormous ego, but he had this self-aware humor. He didn't take himself that seriously. He was an actor. When I started doing the research [for his biography,

The King of Madison Avenue]

I found over and over, the things he said about his life were almost true, but not quite. He embellished.”

Perhaps the best line he ever wrote, certainly the one for which he was most known, was for an advertisement that created an eighteen-month waiting list of potential customers: “At 60 miles an hour the loudest noise in this new Rolls-Royce comes from the electric clock.”

When it was pointed out that it had an unfortunate precedent, some might say beyond coincidence, in a 1933 Batten, Barton, Durstine and Osborn (BBDO) ad “The only sound one can hear in the new Pierce Arrow is the ticking of the electric clock,” his insouciant response was that he didn't steal it from Pierce Arrow, he stole it from a British motoring magazine article. Ogilvy was a fanatically hard worker. “He had no hobbies,” says Roman. “He'd take two briefcases home every night. In

Mad Men

you see people leaving the office to go to bars, to go to the theater. David would leave the theater to go back to the office. I think it broke up his second marriage; he said that he was going to travel the world, do all these things but he didn't. He just worked.”

He smoked, but a pipe only, and liked a drinkâ“I find if I drink two or three brandies or a good bottle of claret, I'm far better able to write”âbut strongly disapproved of drunkenness. He was discreet in any personal antics, deeply attractive to women as he was.

WITH THE 1963 PUBLICATION

of

Confessions of an Advertising Man

, Ogilvy's fame skyrocketed. It's an advertising manual with clearly prescribed chapter subjects but written in a jaunty, informal style, anecdote mixed with homily. Like Reeves'

Reality in Advertising

, it was intended as little more than a manual for his agency and the original print run was five thousand copies. Well over a million have since been sold.

One of the most famous advertising lines of all time; Ogilvy's Rolls-Royce advertisement.

It was a brilliant new business tool, containing chapters guaranteed to catch the eye of potential clients: How to be a Good Client, How to Build Great Campaigns, How to Write Potent Copy, How to Make Good Television Commercials, How to Make Good Campaigns for Food Products, Tourist Destinations, and Proprietary Medicinesâand, typically mischievous, ending with “Should Advertising be Abolished?”

His efforts had paid off; by now, he was one of the very few advertising names known outside the business and fifteen years after he had opened it, his agency was billing $34 million and ranked twenty-eighth in New York. But although there was a residual reputation for great creative work, it was still hanging on early campaigns like Hathaway and that single Rolls-Royce advert. Increasingly, when it came to turning out campaigns, O&M was being seen as creatively near bankrupt.

Part of the problem was Ogilvy's advertising ideology, which seemed heavy-handed and inconsistent throughout the fifties and into the sixties. He was fanatical about detailed analysis of the results of advertising researchâ”This is what I learned from Gallup. I'm obsessed with it”âand about prescribing how an ad should and should not be created. He developed rules for concepts, copy, and layouts with hard facts about effectiveness for any given technique, such as: “Five times as many people read headlines as body copy”; “Research shows that it is dangerous to use negatives in headlines”; “Readership falls off rapidly up to fifty words of copy but drops very little between fifty and five hundred words”; “Always use testimonials.”