The Red Army Faction, a Documentary History (22 page)

Read The Red Army Faction, a Documentary History Online

Authors: J Smith

Left to right: Gabriele Rollnik, Werner Hoppe, and Karl-Heinz Dellwo: three of the many prisoners from the guerilla who were being subjected to torturous conditions at this time.

In order to try and secure his transfer to another prison and integration into general population, Dellwo commenced a hunger and thirst strike on September 21, 1978.

12

The crisis around Dellwo and Hoppe's condition is what pushed some comrades to engage in the most militant aboveground prisoner-support action in years.

On November 6, 1978, eleven masked individuals forced their way into the offices of the

deutsche presse-agentur

(dpa) news agency in Frankfurt. Cutting the telephone wires and tying up the staff, the “Willy Peter Stoll and Michael Knoll Commando” intended to send out a statement about Dellwo and Hoppe on the dpa's newswire. It might have worked, except that an editor managed to trigger a panic button, setting off the alarm at a nearby police station. The cops quickly descended on the premises, arresting the elevenâwho despite carrying out the occupation as a “commando” had only been armed with clubs.

13

As the occupiers explained in a subsequent interview:

We named our action after Willy Peter Stoll and Michael Knoll. For us, these two names exemplify the nature of the overall situation in which we acted. Some of us knew the two personally, but independent of that, the fact that the pigs could insidiously and openly liquidate them, with the left's reaction ranging from bewilderment to disinterest or completely cynical indifference, while the

media celebrated these murders with bloodthirsty outburstsâthat was a slap in the face for us. The murders of Willy and Michael expose our lack of resolve in the face of a development that is deadly in nature and turns resistance into an existential issue. The dpa occupation was a step toward breaking through this, nothing more, nothing less.

14

One of the occupiers was Wolfgang Beer, a former RAF member who had recently been released after spending four years in prison. (He was one of those who had been arrested on February 2, 1974; his younger brother Henning had subsequently become a fixture in the support scene.) Simone Borgstedde and Rosemarie Prieà were also among the occupiers: the two knew Dellwo and other RAF members from their days squatting in Hamburg in the early 1970s, and had more recently lived with Susanne Albrecht before she went under in 1977. Prieà had been arrested along with Volker Speitel in October 1977, charged with support for a terrorist organization, but had been released shortly thereafter. It would come out that the

Verfassungsschutz

âWest Germany's internal political spy agency, the “Guardians of the Constitution” (see sidebar on next page)âhad been bugging the two women's flat since October, raising questions about how much it had known about the occupation beforehand.

15

The eleven would be charged withâand convicted ofâsupporting a terrorist organization, each receiving a one-year prison sentence under §129a. For some, this was not their first such prison sentence, for others, it would not be their last.

16

One month later, over the objections of all three major political parties, the Altona General Hospital had Hoppe transferred to a semi-open unit, in order to provide him with more intensive care.

17

Despite the “antiterrorist” grandstanding being indulged in by the politicians, the medical evidence was incontrovertible, with one doctor after another finding that Hoppe was not fit for incarceration. Bloodthirst notwithstanding, the state had nothing to gain from having a prisoner die like this, especially once the risk had been so clearly established in the

public record. So it was, that on February 8, 1979, the decision was made to release him on grounds of ill health.

18

The dpa occupation represented an attempt by RAF supporters to get back on their feet, part of the process of recovering from the defeat of â77 and the political isolation that had ensued. However, the militant nature of the action (not to mention the fact that nothing actually got sent out over the newswire), meant that its appeal was limited to those already sympathetic to the prisoners' struggle.

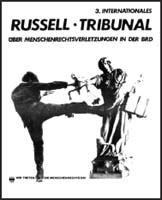

In terms of broader outreach, a more important exercise came in the second phase of the Third International Russell Tribunal on Civil Liberties in West Germany. The first such Tribunal had been held in 1967, as a public body examining and ultimately condemning U.S. war crimes in Indochina. This was followed by a Second Russell Tribunal, investigating political repression in Latin America, provoked in large part by the 1973 Pinochet coup in Chile. The idea of holding a Third Tribunal, on human rights in the FRG, had first been broached at an Anti-Repression Conference held in Frankfurt following Meinhof's death in 1976. With encouragement from Klaus Croissant, different committees were formed in the FRG and abroad to bring the Russell Tribunal to the Federal Republic; its initial hearings would be held in Frankfurt in March 1978.

The decision to hold such a Third Tribunal, now focusing on the internal affairs of a West European country, was a scandal in the eyes of conservative critics, who complained that conditions in the GDR were not going to be similarly examined. As such, the Tribunal's first session, on the

Berufsverbot

âthe law that banned “subversives” from employment in the public sector

19

âreceived a great deal of publicity, much of it negative.

20

Right-wing politicians derided the exercise as the “slaughtering of a democracy,”

21

while several intellectuals close to the SPD organized a “Congress for the Defense of the Republic,” held in Hannover in April 1978, to counter its findings.

22

Verfassungsschutz

Founded in 1950, the

Verfassungsschutz

is West Germany's internal political intelligence service. There is a federal

Verfassungsschutz

and eleven

Länder Verfassungsschutzen,

all of which are charged with collecting information about “enemies of the Constitution” and political extremism, considered security threats regardless of whether or not criminal activity is involved.

In 1972, as a reaction to the appearance of the RAF on the political scene, the SPD passed legislation expanding the powers of the

Verfassungsschutz,

legalizing the use of “undercover informants, clandestine observation, electronic listening devices, hidden video cameras, false documentation, and automobile registration.”

1

(Wiretaps and mail interception were previously unconstitutional.) At the same time, the office's purview was expanded to include both foreign espionage (especially that conducted by the GDR), as well as “foreign residents whose activities endanger or harm the Federal Republic's external interests or security.”

2

Nevertheless, in theory, the

Verfassungsschutz

are “not permitted to stop, question, search, detain, arrest, or interrogate suspects, nor to search private residences, nor to seize personal materials.”

3

Nor is the

Verfassungsschutz

supposed to be able to take any direct action, other than alerting police, against criminal activity. Unlike political police forces such as the FBI, the

Verfassungsschutz

is not empowered to make arrests. This has repeatedly led to murky situations in which undercover

Verfassungsschutz

agents and informants were present during, and participated in, criminal activities.

At the same time, the agency is not obliged to divulge information to either the courts or the police if this would reveal either its sources or methods of collecting information.

(For more on the

Verfassungsschutz,

see Appendix I: Conclusions of the Third Russell Tribunal,

pages 324â325

,

327

.)

_____________

1

Michaela W. Richter,

German Issues 20: The Verfassungsschutz

(Washington DC: American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, 1998), 20.

2

Ibid., 23.

3

Ibid., 18.

For the much smaller number of people who made up the radical left, however, the problem was not that the Tribunal was focusing on West Germany, but that it was prioritizing the issue of the “career ban” over more life-and-death concerns. RAF supporters had been active in organizing the Tribunal from the very start, and yet their standing in the exercise had suffered in the course of the state's crackdown, especially in â77. Police would single out anti-imperialists working on the Tribunal, and as they were thereby tied up dealing with their legal situation more liberal forces were able to gain the upper hand. As one anti-imperialist recalls, over forty years later:

In the end it was impossible to resist the attacks both internal from within the ranks of the Russell Tribunal and external by state forces. Our work in 1977 was smashed in the best meaning of the word. My home in Düsseldorf (like others in other cities) was raided four times by the cops and they confiscated boxes upon boxes of work materials about the prison conditions of political prisoners. I was not arrested for more than two days during those events, but it was not before the end of 1978 that all those materials were given back to me “without comment.” It was quite clear that they just wanted to make it impossible for us to do our work and make the prisoners an important part of the Tribunal.

23

This troublesome situation was made all the more galling as the Tribunal's first hearings occurred in the midst of the RAF prisoners' sixth hunger strike, and ended just a week before the Drenkmann-Lorenz trial was scheduled to begin in West Berlin. Rumors were spread in the right-wing press that RAF supporters might even disrupt the hearingsâa transparent attempt to deepen the rifts that already existed between liberals and radicals. Nothing came of this, of course, but on the opening day of the

Berufsverbot

hearings thirty protesters did occupy a Lutheran church in Hamburg, decorating it inside and out with posters calling attention to the prisoners' conditions. Among their number was Sybille Haag, whose husband Siegfried was a RAF prisoner, and one of those on hunger strike at the time.

24

Such pressure, combined with criticism from sympathetic quarters, including the

Kommunistische Bund,

was successful, and eventually led to a second set of hearings being held in January 1979, in which the Tribunal refocused its attention on political censorship, prison conditions, and the power wielded by the

Verfassungsschutz

in the FRG.

This second set of Russell Tribunal hearings provided a space where those sympathetic to the RAF could work more productively in tandem with civil libertarians and human rights activists who still disagreed with the guerilla's politics, but nevertheless did not countenance the state's violence and repressive legislation.

25

Such cooperation with liberal human rights activists had always been an important part of supporting the prisoners, despite the inevitable frustrations and pitfalls involved. But the situation was made all the more difficult now that the prisoners' most trusted legal representativesâthose best placed to navigate such watersâwere themselves in prison, or facing charges, as a result of the crackdown. Klaus Croissant had been extradited from France on November 17, 1977, and was serving a thirty-month prison sentence for supporting a terrorist organization. Armin Newerla and Arndt Müller were similarly incarcerated as they awaited trial, accused of smuggling weapons into the Stammheim prisonersâan accusation based solely on the testimony of Volker Speitel and Hans-Joachim Dellwo, who had been flipped by the police. For his part, Kurt Groenewold was facing charges that would result in his receiving a two-year suspended sentence later in 1979, condemned for having facilitated communication between the prisoners via the “Info System” between 1973 and â76.

26

Indeed, by the end of â77, these attacks had effectively put an end to the work of the IVKâthe prisoners' support committee founded in 1975 by lawyers from across Europeâin the FRG.

Nonetheless, by the time the Russell Tribunal finished its deliberations, it had condemned the FRG on all counts.

So it was, that much of the public attention paid to prison conditions was thanks to liberal watchdog organizations that certainly shared none of the RAF's politics, for even a narrow civil liberties perspective provided ample scope to identify illiberal excesses in the FRG's war against the guerilla, especially in its dreaded high-security wings.

Another example of this occurred in February 1979, as Amnesty International sent a

Memorandum on Prison Conditions of Persons Suspected or Convicted of Politically Motivated Crimes in the FRG

to the minister of justice, Hans-Jochen Vogel. Here the international human rights organization reiterated the findings of previous inquiries: