The Reenchantment of the World (33 page)

Read The Reenchantment of the World Online

Authors: Morris Berman

the behavioral model, which is most commonly associated with J.B. Watson

and B.F. Skinner. The real grandfather of such work was Ivan Pavlov, who

had managed to immortalize a dog by getting it to salivate when he rang a

bell. What Pavlov did was to set up a context of association. Repeatedly,

bell-ringing was followed by food, until the sound of the bell alone was

enough to trigger the animal's entire gastronomic response. In one of

Skinner's experiments, a rat learned to press a bar and thereby release a

pellet of food. Skinners rat had to contend with a set of rules different

from those that confronted Pavlov's dog, but again a context of (causal)

association was central: event occurs, food appears. Furthermore, all of

these experiments involved a progressively faster rate of learning on

the part of animals. Dog and rat quickly caught on to the rules of the

game. After a number of trials, the dog did not need meat to salivate;

he had learned what the bell meant. Similarly, the rat discovered that

the food pellet was no accident, and began to spend much of its time

pressing the bar.

"discover" mean, as I have just employed them? Bateson uses the term

"proto-learning" to characterize the simple solution of a problem. Bell

rings, or bar is presented. The Pavlovian situation requires a passive

response, the Skinnerian situation a more active one, but there is

still a problem to be solved in each case: what does this phenomenon

require of me (dog, rat), and what does it lead to? Solving such a

specific problem is proto-learning, or Learning I. "Deutero-learning,"

or Learning II, Bateson defines as a "progressive change in [the] rate

of proto-learning." In Learning II the subject discovers the nature

of the context itself, that is, he not only solves the problems that

confront him, but becomes more skilled in solving problems in general. He

acquires the habit of expecting the continuity of a particular sequence

or context, and in so doing, "learns to learn." There are, furthermore,

four contexts of positive learning, as opposed to negative learning,

in which the subject learns not to do something. There are the two

already described, Pavlovian contexts and those of instrumental reward;

and there are also contexts of instrumental avoidance (e.g., rat gets an

electric shock if it doesn't press the bar within a certain time interval)

and of serial and rote learning (e.g., word B is always to be uttered

after word A). So proto-learning is the solution of a problem within

such contexts, and deutero-learning is figuring out what the context

itself is -- learning the rules of the game.

indeed, character and reality prove to be inseparable. A person trained

by a Pavlovian experimenter would have a fatalistic view of life. He

would believe that nothing could affect his state, and for such a person

reality might well consist of deciphering omens. A Skinnerian-trained

individual would be more active in dealing with his or her world, but no

less rigid in his or her view of reality. Western cultures, notes Bateson,

operate in terms of a mixture of instrumental reward and avoidance. Its

citizens deutero-learn the art of manipulating everything around them,

and it is difficult for them to believe that reality might be arranged

on any other basis. The link between fact and value is (a) that such

acquired perceptions are also acquired character traits, and (b) that

they are purely articles of faith. In other words, to take (a) first,

any bit of learning, especially deutero-learning, is the acquisition of

a personality trait, and

what we call "character"

(ethos, in Greek)

is built on premises acquired in learning contexts

. All adjectives

descriptive of character, says Bateson -- "dependent," "hostile,"

"careless," and so on -- are descriptions of possible results of Learning

II. The Pavlovian-trained person not only sees reality in fatalistic

terms; we might also say of him or her, "She is fatalistic," or "He

is a passive type." Most of us raised in Western industrial societies

have been trained in instrumental patterns, and therefore we do not

ordinarily notice these patterns: they constitute our ethos. They are

"normal," and thus invisible. In especially egregious cases, we will say,

"He's only out for himself" -- a character description that is at the same

time an epistemology. Dominant, submissive, passive, self-aggrandizing,

and exhibitionistic -- all are simultaneously character traits and ways

of defining reality, and all are (deutero-) learned from early infancy.

issue of the "true ideology." If you have been raised with an instrumental

view of life, you will relate to your social and natural environment in

that way. You will test the environment on that basis to obtain positive

reinforcement, and if your premises are not validated, you will probably

not abandon your world view, but classify the negative response, or lack

of response, as an anomaly. In this way you remove the threat to your

view of reality, which is also your character structure. Neither the

witch doctor nor the surgeon gives up magic or science when his methods

fail, as they often do. Behavior, says Bateson, is controlled by Learning

II, and molds the total context to fit in with those expectations. The

self-validating character of deutero-learning is so powerful that it

is normally ineradicable, usually persisting from cradle to grave. Of

course, many individuals go through "conversions" in which they abandon

one paradigm for another. But regardless of the paradigm, the person

remains in the grip of a deutero-pattern, and goes through life finding

"facts" that validate it. In Bateson's view, the only real escape is what

he calls Learning III, in which it is not a matter of one paradigm versus

another, but an understanding of the nature of paradigm itself. Such

changes involve a profound reorganization of personality -- a change in

form, not just content -- and can occur in true religious conversion, in

psychosis, or in psychotherapy. These changes burst open the categories

of Learning II itself, with magnificent or hazardous results. (We shall

deal with Learning III at greater length below.)

science denies in principle, occurs quite naturally in Bateson's analysis

of learning. A system of codification, he says, is not very different

from a system of values. The network of values partially determines the

network of perception. "Man lives by those propositions whose validity is

a function of his belief in them," he writes. Or as he says at a later

point, "faith is an acceptance of deutero-propositions whose validity

is really increased by our acceptance of them."

is

character structure? If it was an error to reify ethos

in New Guinea, Bateson realized, it was no less fallacious to treat

a character trait as a thing. Adjectives descriptive of character are

really descriptions of "segments of interchange." They are descriptions

of

transactions

, not of entities, and the transactions involved

exist between the person and his or her environment. No person is

"hostile"

or "careless" in a vacuum, despite the contrary contention of Pavlov,

Skinner, and the whole behavioral school. Clearly, Learning II is

equivalent to the acquisition of apperceptive habits, "apperception" being

defined as the mind's perception of itself as a conscious agent. Such

habits can be acquired in more than one way, and the behaviorist is wrong

to believe that habit is formed only through the repeated experience of a

specific kind of learning context. "We are not concerned," writes Bateson,

events stream, but rather with real individuals who have complex

emotional patterns of relationship with other individuals. In

such a real world, the individual will be led to acquire or reject

apperceptive habits by the very complex phenomena of personal example,

tone of voice, hostility, love, etc. Many such habits, too, will be

conveyed to him, not through his own naked experience of the stream

of events, for no human beings (not even scientists) are naked in

this sense. The events stream is mediated to them through language,

art, technology and other cultural media which are structured at

every point by tramlines of apperceptive habit.19

last

place to learn about

learning, just as the physics laboratory is the last place to learn

about light and color. Both Skinner and Newton were guilty of narrowing

the context to the point that they could have precise control over

the trivial. If you wish to find out about learning, contends Bateson,

study individuals in their cultural context, and study especially the

non-verbal communication that goes on between them. Deutero-learning

proceeds largely in terms of what he would later call "analogue," as

opposed to "digital" cues. It is in this arena that we shall, he believed,

find the source of our character "traits" and our cognitive "realities."

rapidly after Gutenberg s time, is verbal-rational and abstract. For

example, a word has no particular relationship to what it describes

("cow" is not a big word). Analogue knowledge, on the other hand, is

iconic: the information represents that which is being communicated (a

loud voice indicates strong emotions). This kind of knowledge is tacit,

in Polanyi's sense, and includes poetry, body language, gesture and

intonation, dreams, art, and fantasy. Pascal and Descartes had debated

this distinction between style and nuance on the one hand, the measurement

and geometry on the other. Although at first glance these two forms of

knowledge may seem irreconcilable, Bateson chose to believe that Pascal

was right when he wrote that the heart had its reasons which reason did

not perceive. Perhaps it was time for scientists to start formulating

some cardiac algorithms.

playing at the Fleishhacker Zoo in San Francisco, that he realized

that their play (the monkeys' captivity notwithstanding) could provide

a foothold on the whole area of nonverbal commumcation. The resulting

article, "A Theory of Play and Fantasy," argued: (1) that play between

mammals dealt with 'relata,' rather than manifest content, and in this way

was very similar to primary-process material (or dream and fantasy) in its

structure; (2) that although it was not familiar to our conscious minds,

such material was subject to the analysis of formal logic, specifically

the rules of paradox described by Russell and Whitehead in their classic

work, "Principia Mathematica" (1910-13); (3) that since humans were

mammals, our own learning -- and therefore our character and world view

-- depended on such material; that what we called "personality" and

"reality" were formed by a (deutero-) learning process that permeated

our environment and taught us, in ways that were subtle but definite,

certain allowable patterns that the culture labeled "sane"; and (4) that

conversely, insanity (ostensible lack of coherence of personality and

world view) probably involved the inability to manipulate the relationship

between conscious and unconscious according to the deutero-propositions

of a particular cultural context.

and Whitehead's "Theory of Logical Types." In itself, the theory simply

states that no class of objects, as defined in logic or mathematics,

can be a member of itself. Let us, for example, conceive of a class of

objects consisting of all of the chairs that currently exist in the

world. Anything we customarily term "chair" will be a member of that

class. But the class itself is not a chair, any more than a particular

chair can be the class of chairs. A chair, and the class of chairs,

are two different levels of abstraction (the class being the higher

level). This axiom, that there is a discontinuity between a class and

its members, seems trivially obvious, until we discover that human

and mammalian communication is constantly violating it to generate

siginficant paradoxes.

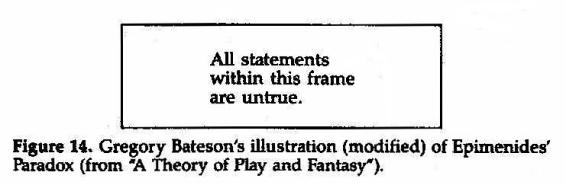

or the "Liar's Paradox" (see Chapter 5, note 30). It might be presented as

in Figure 14:

and if false, it is true. The resolution lies in the Russell-Whitehead

axiom. The word "statements" is being used in both the sense of a class

(the class of statements)

Other books

The Year of the Gadfly by Jennifer Miller

The Reverse of Perfection (Bad Decisions Book 2) by Christi Barth

Ecotopia by Ernest Callenbach

Habit by Susan Morse

El tango de la Guardia Vieja by Arturo Pérez-Reverte

Wicked Deeds by Jenika Snow

Murder at Ebbets Field by Troy Soos

Ode To A Banker by Lindsey Davis

The Boss's Proposal by Cathy Williams

Beanball by Gene Fehler