The Revolt of Aphrodite (52 page)

Read The Revolt of Aphrodite Online

Authors: Lawrence Durrell

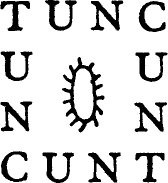

“We rang up Julian and flew him home a sample. Of course we had visualised a vast free distribution of this charm, probably sowed broadcast from the air, but as usual Julian’s keen mind took hold of the problem and solved it. It would have no value to people unless they had to pay for it, he said, and I quite saw his point. We were to give away only a few thousand through the hospitals but put the rest—some four million at first printing—on the open market in order to forestall some similar kind of effort by the Catholics.

Moreover

he offered us one per cent which was really very handsome of him, and which has made us both extremely rich men. So was Koro finally brought under control by the kindly intervention of Tunc. I must say I am sentimental about the little God and always carry one on my watch-chain for good luck—though God knows at my age….”

Musing thus the Count produced a new gold watch-chain of great lustre and showed us a copy of the charm. “A pretty emblem, no?” he said modestly.

“But why in European characters?”

“Foreign magic has great

cachet

there. This was the foreign issue given away by the hospital administration. There was also a local version for sales distribution. We were a little worried about religious sensibilities, but everyone was delighted.

He sighed at the memory of these great adventures and glanced at the pristine gold watch which depended from the chain. “I have a conference” he said. “I must run along. I’ll meet you at the plane at six, Caradoc. Without fail, mind, and don’t lose that ticket.” And so saying he waved us an airy goodbye, only pausing to add over his shoulder, “We’ll meet in London I hope.”

Caradoc squeezed the pot dry and took up the final teacup. “Isn’t it marvellous to see what happens when people really find

themselves?

” It was, and we said so, somewhat sententiously I fear. Banubula had emerged from his cocoon like the giant Emperor moth he had always been and was now in full wing-spread. “You know,” said Caradoc polishing up the butter on his plate with a morsel of tea-cake “that is all that anybody needs. Nothing more, yet nothing less.”

And so at last the time came to take leave of him, which we did with reluctance, yet with delight to know that he was still to be numbered among the living. I spoke to him a little bit about his papers and his aphorisms and recordings—and indeed all the trouble Vibart and I had been to, to try and assemble a coherent picture of this venerable corpse. He laughed very heartily and wiped his eye in his sleeve. “One should never do that for the so-called dead” he said. “But it’s largely my fault. One should not leave such an

incoherent

mess behind. I didn’t know then that everything must be tidied up before one dies or it just encumbers one’s peace of mind when one

is

dead, like I have really been, in a manner of speaking. It

was too bad and I am really sorry. We’ll order things better next time, for my real death. There won’t be a crumb out of place, you’ll see. The whole thing will be smooth as an egg, mark me. Not a blow or a harsh word left over—and even tape recordings burn or scrub don’t they?” He walked us with his old truculent splayed walk to the car-park and waved us goodbye in the misty evening. I looked back as we turned the corner and gave him a thumbs-up to which he responded. Lighting-up time by now with mist everywhere and foggy damp, and the wobble of blazing tram-cars along the impassive avenues. “I feel sort of light-headed,” I said “from surprise I’ve no doubt.”

Benedicta put her hand briefly on my knee and pressed before turning back to the swerves and swings of the lakeside road. “

Perhaps

you’ve contracted Koro” she said.

“Perhaps I have.”

“You must ask for an amulet from the firm.”

“I think I will. You can never be certain in this world; even the innocents like Sipple can get struck down it seems.”

The dark was closing in fast and soon I was drowsing in the snug bucket-seat, waking from time to time to glance at the row of lighted dials on the fascia. “Why so fast?” I said suddenly. “Light me a cigarette,” said Benedicta “and I’ll tell you. Tonight we shall hear from Julian. As it may be a phone-call I suddenly had a guilty conscience and thought we should get back.” I lit the cigarette and placed it between her lips. “And how did you know?” I said. “I had a postcard ages ago giving me this date, but it slipped my mind and I only remembered it all of a sudden while Caradoc was talking. If it’s too fast for you tell me and I’ll slow down.”

No, it wasn’t too fast: but it wasn’t a phone message either. It was a telex to the hospital from Berne, saying: “If Felix feels up to it and if you are free please meet me with a small picnic on the Constaffel, hut five, at around midday on the fifteenth. My holiday is so short that I would like to combine the meeting with a bit of a run on the snow. Will you?”

“The polite request disguises the command” I said. “Shall I decline? And what the devil is the Constaffel?”

“It’s where the practice slopes begin up on the mountainside; the

Paulhaus always keeps a camper’s hut available there for the use of convalescents.”

“Look Benedicta,” I said severely “I am not webtoed, and I am not going to scull about in the mountains on skis in my present state of health.”

“It’s not that at all” she said. “We can go up with the

t

é

l

é

f

é

rique

and the hut is about five hundred yards along the cliff-face with a perfectly good path to it. It won’t be snowed up in this sort of weather. We could walk, if you’ll go, that is. If not let me send him a cable.”

I was tempted to give way to an all too characteristic petulance but I reflected and refrained. “Let us do it, then” I said. “Yes, we’ll do it. But I warn you that if he appears disguised as the Abominable Snowman I’ll hit him with an ice pick and polish him off for good and all.”

“I count on you.”

They were easily said, these pleasantries, but in the morning lying beside her warm dent, her “form”, while she herself was making up her face in the little bathroom next door I found myself wondering what the day would bring, and what new information I would glean from this encounter. I went in to watch her play with this elegant new face, now grown almost childish and somehow serene. She had only half a mouth on which made me feel hungry. “Benedicta, you don’t feel apprehensive about this, do you?”

She looked at me suddenly, keenly. “No. Do you?” she said. “Because there’s no need to go. As for me I told you I had come to terms with Julian. I’m not scared of anything any longer.” I sat down on the

bidet

to wash and reflect. “I used the wrong word. What I dread really is the eternal wrangle with people who don’t understand what one is trying to do. I fear he’ll just ask for me to come back, everything forgotten, but never to try and run away again. It’s what they do to runaway schoolboys at the best schools. Whereas I am not giving any guarantees to anyone. I intend to always leave an open door.” Benedicta finished her mouth and eyes without saying anything

.

Then she went out and I heard her giving Baynes instructions about thermos flasks and sandwiches. So I shrugged my shoulders and had a shower.

The day was fine and bright and really ideal for non-skiers; this year there had been very little snow and the press had made great moan about the fact that the season would be blighted because of it.

Rackstraw had seen some reference to the matter in a paper and had kept on about it until I could have strangled him. In the old days he had been, it seems, some sort of ski-champion. Though no longer allowed out he kept a close eye on weather and form. Anyway, this was none of my affair, and about half past ten we set off—she in her elegant Sherpa rig of some sort of mustard-coloured whipcord—towards the

t

é

l

é

f

é

rique

which we found quite empty. Operated by remote control, it was an eerie sort of affair, the doors flying open as one stepped upon the landing-ramp and closing behind one with a soft whiff. We had the poor snowfalls and the excited press to thank for the empty car in which we sat, sprawling at ease among our packs and other impedimenta, smoking.

A few moments’ waiting and then all of a sudden the cabin gave a soft tremor and began to slide forwards and upwards into the air, more slowly, more deliriously than any glider; and the whole range of snowy nether peaks sprang to attention and stared gravely at us as we ascended towards them, without noise or fuss. Away below us slid the earth with its villages and tracery of roads and railways—a diminishing perspective of toy-like shapes, gradually becoming more and more unreal as they receded from view. The sense of aloneness was inspiriting. Benedicta was delighted and walked from corner to corner of the cabin to exclaim and point, now at the mountains, now at the snowy villages and the dun lakeside, or at other features she thought she could recognise. The world seemed empty. Up and up we soared until we had the impression of grazing the white faces of the mountains with the steel cable of our floating cabin. “I don’t know whether Julian is doing the sensible thing” she said “in ski-ing about up here; the surfaces have been flagged here and there for danger and there have been several accidents.” The lift came slowly to a halt in all this fervent whiteness, slid up a small ramp and stopped with a scarcely perceptible shock. The doors opened and the cold world enveloped us. But the sunlight was brilliant, dazzling, and the snow squeaked under our boots like a comb in freshly washed hair. Nor was it far along the scarp to where

the ski-huts stood; it was from here that the serious performers started their ascent. Benedicta had the key and we opened up the little hut which was aching with damp and cold, but fairly well equipped for camp life. There was a little stove which she soon had buzzing away—it promised us hot coffee or soup to wash down the fare we had brought. We settled ourselves in methodically enough. Then outside in the brilliant sun we smoked and had a drink together and even embarked on a snow man of ambitious size. There had been several bad avalanches that year and I was not surprised when one took place there and then, as if for our personal delectation. A white swoosh and a whole white face of the mountain opposite cracked like plaster, hesitated, and then broke away to fall hundreds of feet into the valley. The boom, as if from heavy artillery,

followed

upon the spectacle by half a minute almost.

“That was a good one” said Benedicta.

There were some tree stumps and a wooden table under the fir in front of the hut, and we cleared these of snow and set out plates and cutlery thereon. We had all but finished when by chance I happened to look upwards along the crescent-like sweep of the mountain above us. Something seemed to be moving up there—or so it seemed out of the corner of my eye. But no, there was nothing. The

unblemished

snow lay ungrooved everywhere on the runs. I turned away to the opposite side and saw with a little shock of surprise a lone skier standing among a clump of firs, watching us like a

sharpshooter.

We stayed for a long moment like this, unmoving, and then the figure, with the sudden movement of a Red Indian sinking his paddle into the river, propelled himself forward and began to ripple down towards us, cutting his grooves of whiteness on the clean snow.

Fast, too, very fast. “Could that be Julian?” I said, and Benedicta following the direction of my pointing finger with eyes screwed up said: “Yes. It must be.” So we stood hand in hand watching while the small dark tadpole rushed towards us, growing in size as it came, until we could see that it was a man of about medium height, rather gracefully built in a slender sort of way, and as lissom on his skis as a ballet dancer. When he had reached the little fir about fifty yards off he swerved and braked, throwing up a white fountain of snow; he took off his skis and made his way towards the hut beating the snow

from his costume with his heavy mittens. “Hullo” he cried with great naturalness, as if this were not a momentous, a historic meeting, but a casual encounter between friends. “I’m Julian at last” he added. “In the flesh!” But of course in his ski get-up there was nothing very distinct to be seen as yet. Then I noticed that there was blood running from his nose. It had dried and caked on his upper lip and in the slender perfectly shaped moustache. He dabbed it with a handkerchief as he advanced, explaining as he came. “I tend towards an occasional nose-bleed up at this level—but it’s well worth it for the fun.” His nostrils were crusted with blood, though the flow appeared to have stopped.

We shook hands, gazing at one another, while he made some

perfectly

conventional remark to Benedicta, perfectly at ease, perfectly insouciant. “At last,” I said “we meet.” It sounded somehow fatuous. “Felix,” he said in that warm caressing voice I knew so well (the voice of Cain) “it’s been unpardonable to neglect you so but I waited until we could talk, until you felt well and unharassed by things. You are looking fine, my boy.” I gave him a clumsy Sherpa-like bow which conveyed I hoped a hint of irony. “As well as can be expected” said I. He still kept on his heavy mica goggles tinted slightly bronze so that I could not really see his eyes properly; also of course the padded suit and the peaked snowcap successfully muffled all clear outlines of his head and body. All I saw was a very delicately cut aristocratic nose (like a bird of prey’s beak), an ordinary mouth with blurred outlines because of the bloody upper lip, and the small feminine hand with which he grasped mine. Benedicta offered to swab his lip with cotton wool and warm water but he refused with thanks saying: “O I’ll clean up when I get down to terra a little firma.” So we stood, eyeing each other keenly, until Benedicta brought out some drinks and we settled down opposite him at the wooden table to drink gin slings in the sunny whiteness. “Where to begin?” said Julian with a melodious lazy inflexion which was very seducing—the calm voice of the hypnotist. “Where to begin?” It was indeed the question of the moment. “Well, the circle can be broken at any point I suppose. But where?” He paused and added under his breath “Running into airpockets, ideas in flight!”