The Rise & Fall of ECW (2 page)

Read The Rise & Fall of ECW Online

Authors: Tazz Paul Heyman Thom Loverro,Tommy Dreamer

The first

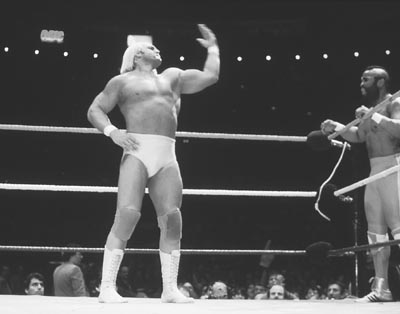

WrestleMania:

Hulk Hogan with his tag partner, Mr. T.

Two years later,

WrestleMania

had become something the likes of which the sports and entertainment business had never seen before.

WrestleMania III

drew 93, 173 people at the Pontiac Silverdome in Detroit. With Aretha Franklin singing “America the Beautiful,” the show featured the historic showdown between Hogan and the great Andre the Giant, whom Hogan bodyslammed and then legdropped to win the match.

Drawing Pay-Per-View numbers that are often over one million buys,

WrestleMania

has been running now for twenty-two years.

WrestleMania XXI

was held in Los Angeles at the Staples Center, drawing more than 20,000 fans to the venue, and was seen in more than ninety countries. It is one of the most popular entertainment events in the world, and has helped turn the WWE, World Wrestling Entertainment, into a powerful media empire.

Success didn’t happen without a fight, as WWE battled many entities along the way, including World Championship Wrestling (WCW), led by the powerful media honcho Ted Turner.

WCW originated from two companies operated by Jim Crockett Promotions—Georgia Championship Wrestling and Mid-Atlantic Championship Wrestling. In November 1988, Crockett sold the promotions to TBS Superstation in Atlanta and Turner, the flamboyant but visionary media mogul who created CNN. Turner had used wrestling shows as part of his programming for TBS Superstation, but he wanted to own the programming and expand it to his other network, TNT. He dropped the organization’s affiliation with the NWA and created a new name for the promotion, World Championship Wrestling. With that, a new era of wrestling wars began.

WCW began raiding talent from other companies, wooing some of the biggest stars in wrestling, such as Hulk Hogan, Bret Hart, and Kevin Nash. And developed a stable of performers such as Sting and Ric Flair. Hogan turned heel while in WCW, with a storyline in which he joined a supposed invading renegade faction of WCW led by Kevin Nash and Scott Hall, called the New World Order—nWo.

WCW took on WWE head-to-head in what was known as the “Monday Night Wars,” when WCW programmed a show called

Monday Night Nitro

against

Raw.

With former announcer Eric Bischoff running the WCW promotion,

Nitro

eventually passed

Raw

in the television ratings.

Monday Nitro

beat

Raw

in the ratings for eighty-four consecutive weeks. The rivalry grew so fierce that Bischoff challenged Vince McMahon to a fight on

Nitro,

and Bischoff put

Nitro

on a couple of minutes before

Raw

so he could give away the results of the taped

Raw

program, giving fans no reason to watch the competition.

Nitro

became a three-hour show, something never seen before in a live wrestling show.

But the tide turned when Vince McMahon developed a new generation of wrestlers that caught the attention of a new generation of wrestling fans, with stars like Triple H, Mankind, The Rock, and an outlaw rebel wrestler named Steve Austin, who became one of the biggest stars in the history of wrestling. WWE eventually won enough battles to win the war. Their storylines were fresher and more provocative, and WCW’s proved to be stale and boring. Eventually, to the victor would go the spoils.

Nitro

went off the air in March 2001, and Vince McMahon would purchase what remained of the WCW, the last man standing in the battle of the 1990s in the business, and he remains in that position today.

In the middle of this war, another fighter rose up and lit a fire under the wrestling business, shaking both of these giants who had been battling for total control of the industry. It was lit in Scarsdale, New York, in the late 1970s, when an enterprising son of a trial lawyer, Richard Heyman, and a concentration camp survivor, Sulamita Heyman, wasn’t satisfied with simply watching wrestling. Paul Heyman wanted to be near the show, around the show, part of the show.

Paul Heyman wanted to be the show.

By the age of 11, Heyman was an entrepreneur, collecting movie memorabilia and then selling them in a mail order business. “I used to collect movie posters, lobby cards, 8-by-10s and stuff like that,” he said. “I opened up a mail order business with a P.O. box. I used to sell movie posters. I would go down to the city and buy them wholesale and then sell them through the mail.”

By the time he was 13, wrestling had captured his heart. Shortly after midnight one night he was watching a show that competed with McMahon’s; it was produced by Eddie Einhorn, one of the owners of the Chicago White Sox. “I saw Argentina Apollo and Luis Martinez, against Hartford and Reginald Love, managed by George ‘Crybaby’ Cannon,” Heyman said. “At the end of this match, Argentina Apollo stole Crybaby Cannon’s army helmet and smacked him in his big belly with it. Crybaby Cannon was crying in his corner as they went off the air. I thought it was the greatest thing I ever saw.”

The next time he saw wrestling on TV, it was a McMahon show, and it featured an interview with “Superstar” Billy Graham. “I can’t tell you what he said,” Heyman claims. “It didn’t really make any sense, but I didn’t care. He was so charismatic. He came right through the television. He blew me away. It was an amazing moment. I thought he was great television, and I was hooked from that moment on.

“I sold out my inventory and bought some photo-developing equipment and a printing press, and started doing newsletters, called

The Wrestling Times

—‘All the wrestling news that was fit to print.’”

Heyman kept trying to get access to wrestling shows as a journalist-photographer, and eventually hustled his way into what is now, looking back, a famous meeting between himself and the boss of the World Wide Wrestling Federation, the elder Vince McMahon. Remarkably, Heyman was only 14 years old. McMahon had little idea he was talking to the future of the business. But he must have realized Heyman was something special.

“Right after I turned 14, I called and asked for Vince McMahon,” Heyman recalls. “I had a deep voice when I was 14 and sounded a lot older than I was. So I said, ‘This is Paul Heyman, calling for Vince McMahon.’ I guess since I had the attitude like I owned the joint, after about five people I got through to him. I was 14 and totally full of shit, with braces on my teeth and pimples on my face, and a whole lot of chutzpah.”

Heyman said to McMahon, “Hi, it’s Paul Heyman.”

McMahon replied, “Who?”

“Paul Heyman, from

The Wrestling Times,”

Heyman said.

“What can I do for you, Mr. Heyman?” McMahon asked.

“You told me to call you for a press pass for Madison Square Garden,” Heyman said.

“I did?” McMahon asked, perplexed, since he didn’t remember telling the young Heyman any such thing—with good reason, because he never had.

“Yes, you did,” Heyman said.

So McMahon told Heyman to go to the second floor of the Holland Hotel in midtown Manhattan, where they had an office for credentials and other business, and ask for Arnold Skaaland, a former wrestler and manager and a long-time fixture at the WWWF, for a press pass.

Heyman took the train into town and went up to the second floor of the Holland Hotel. There he found Skaaland, smoking a cigar and playing cards with Gorilla Monsoon, a legendary WWWF wrestler who would go on to be an announcer. When they saw this 14-year-old kid with pimples on his face and braces on his teeth asking for a press pass, they laughed at him.

“Who told you to get a press pass?” Skaaland asked.

“Vince McMahon,” Heyman answered.

“Okay, kid, I’ll look for you,” said Skaaland, winking at Monsoon about the joke.

But it was no joke. There was a VIP press pass there for Paul Heyman.

“Well, what do you know,” Skaaland said, befuddled.

So on the night of the show, Heyman made his way into the Garden, wearing his press pass and carrying his camera. “A lot of the photographers already knew me because I had made such a pest of myself already trying to get in,” he said. “They asked me, ‘How did you get that press pass?’ I said, ‘I called Vince, Senior.’”

He began taking pictures, and took one particular shot of Andre the Giant and the elder McMahon talking in a hallway. “I knew that the McMahons had an affinity toward Andre,” Heyman said. “They genuinely liked him and he genuinely liked them.”

So the next time he saw McMahon, he had ready for him an 8-by-10 print of the photo.

Heyman walked over to McMahon and said, “Here, this picture is for you.”

“Who are you?” McMahon asked.

“Paul Heyman,” he replied, and McMahon sort of shooed him away.

A few minutes later, McMahon’s public relations man, Howard Finkel, cornered this kid who had given McMahon the photo, and gave Heyman $50.

“Mr. McMahon really liked that picture,” Finkel said. “Now see if you can stay out of sight and out of mind and confine yourself to the press locker room and ringside, and thank you for the picture. Do you mind if we use it in a program?”

Heyman said sure, use it. “I will send you a bunch more pictures,” he told Finkel.

So the kid from Scarsdale began sending photos to the WWWF for use in their program, and he began to get to know people in the business.

“Any time I did photos for the programs, the deal was that I had to have an ad in there for my newsletters or fan clubs or whatever other businesses I was doing at the time,” Heyman says. “I took ads out in wrestling magazines, and also got noticed by word of mouth.”

Those around him recognized that Heyman had a style and manner well suited for the wrestling business, and started encouraging him to get on the inside of the industry. “I was always intrigued by the behind-the-scenes aspect,” he said. “I loved how a show was put together. I loved the planning of it and the creation of the characters and the creation of an event and how a match was structured. I always wanted to produce and write and direct, more than performing. But I was getting noticed as someone who could talk fast and draw attention to myself, so I was getting nudged into the business.”

Heyman, now 19 and a student at Westchester Community College, had a number of irons in the fire, none of them very conventional. He was working at the college radio station. He was also publishing several wrestling magazines. And he wound up doing public relations work for one of the most famous nightclubs of the eighties—Studio 54, the place where people went to see people and to be seen.

At the time, there was a promotion called Pro Wrestling USA, featuring a flamboyant wrestler named “Gorgeous” Jimmy Garvin. Garvin had the image of being this party hound, hanging out at all the hot spots from New York to Vegas and Monte Carlo to the French Alps. “I thought it would be great to take pictures of ‘Gorgeous’ Jimmy Garvin all around the hot spots in New York,” Heyman says. “Even in 1985, the world’s most famous nightclub was Studio 54. I called them up and had a messenger take over a bunch of my magazines. I said, ‘Listen, this is an audience that you don’t hit, and if you want to do Blue Collar Wednesdays or Friday Nights, I could promote it in the wrestling magazines. If you are interested, I could bring a wrestler. If not, we could go someplace else.’

“The general manager called me back and said, ‘Yes, we would love to have you,’” Heyman remembers. “‘Come by with your wrestler and take pictures, and we will do something with it.’”

He took Garvin to Studio 54 and did the photo spread, and the nightclub operators offered him a chance to take some photos for them, since their own house photographer was away for the weekend. While Heyman was there that weekend, Boy George came to town and hit Studio 54 with his lover, a cross dresser named Marilyn. Heyman could see that Boy George was under the influence of some substance, and alerted club management of a potential public relations disaster. The press got wind that Boy George was at Studio 54, and the paparazzi were on their way over.

“George was a mess,” Heyman recalls. “He was barely conscious. I pulled the guy aside who gave me the job and said, ‘If the media comes in here and sees this, you’re going to look terrible. This guy is all messed up.’ So we took George up to the VIP lounge upstairs and kept the media away from him.

“I told George when the night was over, I wanted two pictures of him and Marilyn, by the back door, which you can’t tell is different from the front door because it has the same Studio 54 sign on it. ‘I just want to take two pictures, and then no one will bother you all night long.’”

Heyman took the photos, developed them, and dropped them off at offices of the

New York Daily News

and the

New York Post.

He told photo editors at both papers that he wasn’t looking for money or credit if they used the photos, which they did. He quickly got a call from Studio 54 managers who wondered how Heyman managed to get the publicity shot in the tabloids. “I told them I’m a hustler,” he said. “I can do that for you all the time.”

It was at Studio 54 that Heyman developed some of his promotional skills and his ability to connect with pop culture—something that would later serve him well in the wrestling business. He went from taking pictures to producing Friday night shows at the nightclub—concerts, record releases, parties, and the like. Heyman eventually worked his wrestling connections into club promotions, and created an event called the Wrestling Press International Man of the Year Award. Running about five magazines at the same time, Heyman made a deal with Jim Crockett Promotions and the NWA that if they could deliver Ric Flair, Dusty Rhodes, and Magnum T.A. to Studio 54 for this ceremony, he guaranteed he would get coverage in

USA Today,

in addition to the wrestling magazines he was running. So on Friday night, August 23, 1985, the marriage of Studio 54 and pro wrestling, with Paul Heyman presiding, took place. They had Ric Flair get the WPI Man of the Year award, and actually set up a ring in the nightclub for a match featuring a newcomer named Bam Bam Bigelow. It made a number of papers, and Heyman got the promotional itch. “I kind of got a taste for running a wrestling event and really enjoyed it,” Heyman said. “I knew that to have any credibility in the business, I needed to be more than a magazine guy. Otherwise I am just a press guy trying to see the other side of the coin, instead of being an inside guy who knows how to do media.”