The Rising Tide: A Novel of World War II (44 page)

Read The Rising Tide: A Novel of World War II Online

Authors: Jeff Shaara

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #War & Military, #Action & Adventure

He thought of the message from Marshall, the unmistakable urgency of a man too nervous to wait for Eisenhower’s own cable.

Is the attack on or off?

The message had come several hours before the deadline, and Eisenhower had not yet been prepared to respond, could only wait in raw agony at Cunningham’s headquarters, staring at wind machines, the British sailors making their estimates, predicting the unpredictable. Eisenhower had simply stayed out of the way, letting the weather specialists do their job, reports called out to Cunningham, their jargon,

force four,

and then,

force five.

He didn’t know the precise meaning, how that translated to miles per hour, but outside, after hours watching the rapidly spinning wind machines, standing upright against the hard gale, Eisenhower knew they could be in serious trouble.

He kept Marshall’s cable in his pocket, would wait until the last possible minute, knew that once the order was given, there would be no turning back. There had been some encouraging reports from the navy southeast of Sicily, that since Montgomery’s landing zones were mostly on the leeward side of the island, the landing craft there could push ashore without difficulty. But along the southern coast, the waves were pounding the rocks, deep swells rolling the ships and the landing craft, Patton’s troops huddled in what Eisenhower could only guess was a growing plague of seasickness.

After long hours with Cunningham, Eisenhower was running out of time. There was some encouragement at least, the weather specialists predicting that by midnight the wind would die down considerably. It was the one piece of news on which everything turned. With one hour to go before the planes left Kairouan, Eisenhower radioed Marshall. The attack was on.

H

e tried to see his watch, too dark, stared up again, ignored the men behind him, staff officers, watching as he was, searching for some glimpse of the planes. He had stopped thinking about the ships at all, knew that Patton would do what had to be done. Even if there was a delay along the south coast, Montgomery could get his people ashore, which would draw enemy resistance that way, taking considerable pressure off the American landing zones. It will work, he thought. One hundred sixty thousand men. I don’t care how many tanks they have, we have good people and, dammit, we’re simply better than they are. There is no other way to look at it. What the hell are the Germans fighting for? What

cause

is so damned important? When it comes down to guts, you have to believe that you’re dying for something worthwhile. Dying for a man like Hitler is not worthwhile.

It was a futile pep talk, and the words drained from his mind, replaced by the one image he had fought against, unavoidable. Weeks earlier, he had spent long hours discussing and analyzing this operation with the Eighty-second Airborne’s commander, Matthew Ridgway, and Ridgway’s subordinate Jim Gavin, the man who would lead the paratroopers in their jump. Eisenhower had learned a great deal more about paratroop operations than he had ever known before, and Ridgway’s words were digging at him now.

Fifteen miles per hour.

That was the limit, the maximum wind speed that Ridgway insisted would allow a safe jump. He closed his eyes now, felt the buffeting wind on his back, thought, it’s a hell of a lot more than that now. It shouldn’t be. It’s midnight, for God’s sakes, and this hasn’t let up.

Force five.

Does Ridgway know that? Gavin? They have to, it’s their job. They have to know what they’re being asked to do.

There was a voice behind him, arms in the air, pointing. He looked up, saw it now, the glimmer, more reflections, a string of planes. He forced himself to watch them, tried to say a prayer, ask something, what? Protect them? He pushed it away, no, you cannot do that. You cannot think of the men, what might happen. They are one part of the whole, and the whole is what matters. It is

all

that matters.

He stared up, the wind rocking him again, harder still.

32. ADAMS

OVER THE MEDITERRANEAN

JULY 9, 1943, MIDNIGHT

T

hirty-five miles per hour.

Adams had been close to the cluster of officers, heard the grim reports, Gavin’s simple response: “What the hell do you expect me to do about it now?”

As they gathered at the planes, the men had been fully loaded, pockets and pouches bulging and heavy. More equipment was hanging from the C-47s themselves, mortars and heavy machine guns wrapped in canvas bundles, hooked beneath the wings. Adams had struggled to keep the dust out of his eyes, trying not to think what the strong winds could mean to the paratroopers. After checking his own equipment, he had moved to each man in the stick, silent coaching, every man stuffed and wrapped with every conceivable tool and weapon he had been trained to carry. A few men had tried to talk, spending their nervousness in chatter, mostly to themselves. But there had been none of the joking, the teases, no one had been playful. For so many months they had tormented their bodies and tested their courage, and Adams felt the strength of that, knew they all felt it, that there was a kind of power in them that made them better soldiers than anyone they would face, maybe anyone else in the world. As the time grew closer, the sounds had been few, the men around him buckling up and cinching the straps, hoisting the chutes onto their backs, counting their grenades and their ammunition clips, checking every piece of gear in every pocket, and then, checking it again.

They had climbed aboard the C-47 after dark, close to eight thirty, the briefings from the officers locked in their minds. It was a three-and-a-half-hour flight, nearly all of it over water, and so each man had his Mae West strapped on as well, one more encumbrance. No one had complained.

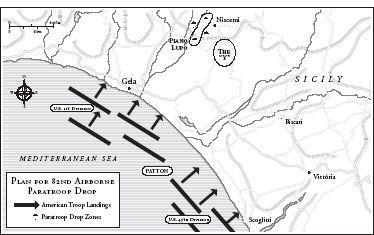

The C-47 would carry a stick of eighteen paratroopers plus the two pilots up front, whose job it was to negotiate the route laid out on the maps. They would fly at a low altitude, keeping close to the water until they reached the coastline. The C-47s were to follow a circuitous route around the massive invasion fleet, avoiding friendly fire from overanxious antiaircraft gunners on the Allied ships. But the briefings had dealt more with the paratroopers themselves, the location of the drop zones, what they would find there, and what they were supposed to do about it. The drop zones were several miles inland, east and north of the coastal town of Gela, directly north of the Acate River. There were specific targets, one crucial intersection of roads that led away from the coast, designated Objective Y, which was guarded by a heavy concentration of pillboxes and gun emplacements. To the northwest of the drop zones was a hill named Piano Lupo, which commanded a view of the Gela airfield. If all went according to plan, the vital routes the enemy could use to confront the amphibious landings would be closed off, and once captured, the Gela airfield could be used immediately to ferry in supplies and reinforcements. Once the Y was cleared, the routes inland would be open for the two infantry divisions, the First and the Forty-fifth, the men who would make their landings on the beaches closest to the 505th’s drop zones. The first part of the mission might be the most difficult, finding the drop zones in moonlight, in the teeth of what continued to be gale-force winds.

Adams didn’t know how many planes had taken off from the various fields around Kairouan, but he knew the men, knew that thirty-four hundred paratroopers had gone aloft in the skies around him, every one with the same job, the same information, and every one carried the same piece of paper, the final message passed out to them from Colonel Gavin.

Soldiers of the 505th Combat Team

Tonight you embark upon a combat mission for which our people and the free people of the world have been waiting for two years.

You will spearhead the landing of an American force upon the island of Sicily. Every preparation has been made to eliminate the element of chance. You have been given the means to do the job and you are backed by the largest assemblage of air power in the world’s history.

The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of every American go with you….

A

dams sat up front, closest to the pilots, would be the last man out of the plane. At the rear sat Ed Scofield, the captain wrapped and buried under his own bundle of equipment and tools, squeezed into place against the man beside him. Scofield sat closest to the open jump door and, when the time came, when the green light flashed, would be the first man to jump.

The plane dipped, tilting to one side, the pilot pulling it straight again, groans from the men. They were used to bounces and air pockets, but this was different, a violence in the sky around them that grabbed the plane like a child’s toy, tossing it from side to side. Adams had tried to sleep, strong advice passed along from Gavin. Captain Scofield had reminded them that once they were on the ground, no one was likely to do anything but move and fight. With daylight coming five or six hours after they landed, it was going to be a long day.

Adams leaned back, his head held upright by the chute. There was no sleep, his mind working furiously, watching the others, keeping an eye on the men who might weaken, who might require some extra jolt from their sergeant. He didn’t want to believe that anyone would fall apart now. These men had been through too much, and even the weakest link in this one chain was strong enough to finish the job they were supposed to do. He ran the names through his mind, tried to predict. McBride, O’Brien? They’ve been pretty good lately. Hell, I was bitching about the desert as much as they were, and I grew up in this kind of crap. Fulton? No, he’s all right. A weak gut doesn’t mean he isn’t a good soldier. Adams sat back again, took a deep breath, felt the calmness of the cool air. It was the one blessing, a hard chill, the jolting turmoil of the flight eased by the coolness around them. There was no worse combination for airsickness than rough air and heat, and they had suffered through plenty of both over Fort Benning. But now, even in the chill, Adams had watched his men carefully, looked for the telltale signs, hands covering mouths, men suddenly lurching over, sickening smells that would infect the rest of them. There had been a few, but only a few, early, some men succumbing within the first hour of flight. But that was sickness of a different kind, the gut-churning fear, the first time any of these men would actually face the enemy. Adams knew that each man held to his own thoughts, some praying, others reciting the letters they had left behind,

I might not return…

, others simply staring into their fear, doing all they could to hold away the terrifying fantasies of what was waiting for them on the ground. When the smells of sickness had drifted through the plane, they all knew that some were better at it than others.

He had left his own letters, one for his mother of course. That one was easy, full of sentiment and soft confidence, all the things she would expect to read, that any mother would want to read. But then he had written to his brother, surprising himself, the words flowing out in a rapid stream, things he would never say to anyone else, things he knew the censors might have some problem with. He didn’t yet know what kind of experiences his brother had seen, what it was really like for a Marine in the Pacific, whether Clayton had actually faced the Japanese, whether he had been wounded, whether he was even alive. No, Adams thought, the army would tell me that. They’re supposed to anyway. But, who the hell knows what those jungles are like, islands in the middle of nowhere. Clayton may never get the damned letter. But, I had to write it. Had to tell someone. I’ll bet he’d do the same. Maybe already has. He thought of Gavin, the assembly one morning, months ago now.

Any man tells you he’s not afraid going into combat, the first thing you do is shake his hand. Then, you call him a liar.

There had been protest after that, the mouthy boys making their speeches about all the things they’d do to the Nazis. But Adams knew in some instinctive place that Gavin was right, that when the time came, when the jumps would land them right into an enemy’s camp, or right beside a ten-gun pillbox, well, damned right I’ll be afraid. And that’s…right now.

He leaned forward, saw Scofield at the rear of the plane, staring down through the jump door. There had been a wager, some of the men wondering what the captain would do when he jumped. It had become customary now that as every man jumped, he yelled out “Geronimo.” The custom was cloudy in origin, some claiming to have started the ritual themselves. Adams was convinced that it had started with a movie the men had watched at Fort Benning. It was a forgettable story, some typical Hollywood version of cowboys and Indians, except for one climactic moment, when the famed Indian chief called out his own name as he purposely rode to his death over a cliff. Only the most gullible believed that the real Geronimo had done such a thing, but the men had decided it made for a dramatic way to depart a plane. The officers mostly ignored the ritual, but Captain Scofield was closer to his men than some of the others, had commented that he might just take up that call himself. Adams had his doubts. It was one thing to emulate some famous Indian when your supposed death leap was over a jump zone in Georgia. It was quite another for an officer to imitate a lusty embrace of certain death when the jump might be exactly that.

He tried to see his watch, too dark, knew they had been aloft now for hours.

George Marshall.

He shook his head.

George Marshall.

Someone’s idea of a joke, maybe. But we’ll remember it. Damned well better.

It was the call sign; once they were on the ground in the dark, no one could know if the first man he contacted was friend or enemy. The entire jump team had been given the code words, the one-word greeting:

George;

and the response:

Marshall.

They could have come up with something better, he thought. How about

Rita Hayworth

? Well, maybe not. Even the Krauts might answer to that one. He scanned the men closest to him, leaned forward again, looked down the rows of men facing each other, no one moving. At the rear of the plane Scofield suddenly rose to his feet, surprising him, the captain moving forward, the men pulling in feet and legs, making way. Adams felt a jolt of concern, waited for Scofield to move close, said, “What’s up, Captain?”

Scofield ignored him, moved into the cockpit, his voice just reaching Adams over the drone of the motors.

“You want to tell me where the hell we are?”

Adams felt a stab of cold curiosity, leaned forward, stared out the small window across from him. There was nothing to see, moonlight reflecting on black water sliding by only a few hundred feet below them. He twisted around, looked behind him, the window close by his own head, saw a speck of light, low on the horizon. And now, a streak of white lights, rising up, and another, his brain kicking into gear.

Antiaircraft fire.

Scofield was still in the cockpit, passing words back and forth with the pilots, and Adams stared at the lines of tracer bullets, more of them, closer now. The plane rocked suddenly, a white flash in his eyes, loud curses beside him, the men coming to life.

“What the hell?”

“We hit?”

“What is it, Sarge? What’s going on?”

Adams called out, “Shut the hell up! It’s ground fire. We’re getting close. Keep calm. Nothing we can do about it.”

He stared out the small window again, heard Scofield, a hard shout: “Turn this son of a bitch around!”

The plane dipped to one side, a hard banking turn, more streaks of white light, a heavy rumble, the plane bouncing, another bright flash. Scofield stayed in the cockpit, and Adams felt himself rising up, straining under the weight of his gear, but he could not just sit. He eased up behind Scofield, said, “What’s going on, sir? We okay?”

Scofield turned to him now, looked past him, eyed the men. “All right, there’s no secrets now. You men need to know that our pilots are not sure where the hell we are. You see those tracers? That ground fire?”

“Yes, sir.”

“That’s supposed to be on the right side! The coastline is supposed to be

that way

…north of us. But that fire is on the left! The jackasses flying this plane can’t find their asses with broomsticks! Sit down, Sergeant! We’ll sort this out if I have to toss these idiots into the ocean and fly this thing myself!”

Adams obeyed, felt a new kind of fear, realized Scofield was as angry as Adams had ever seen him. He looked again through the window behind him, the coastline gone now, the plane still rocking from the gusting wind, another hard bounce. He heard Scofield again.

“There! Follow that beach! You see those ships out there? Those are ours! Stay the hell away from them. There’s ack-ack up ahead, aim for it. That has to be the enemy. If they’re shooting, it means our planes are passing through there. Keep your heading west!”

Adams watched the men, saw faces all looking forward, tense, silent men, the only voice the captain’s. There were more flashes now, to the right side, and suddenly there was a chattering sound, like the rattle of so many pellets against the aluminum skin of the plane. The men were moving about now, twisting toward the windows behind them, useless with so much encumbrance.