The Road Through the Wall

PENGUIN CLASSICS

CLASSICS

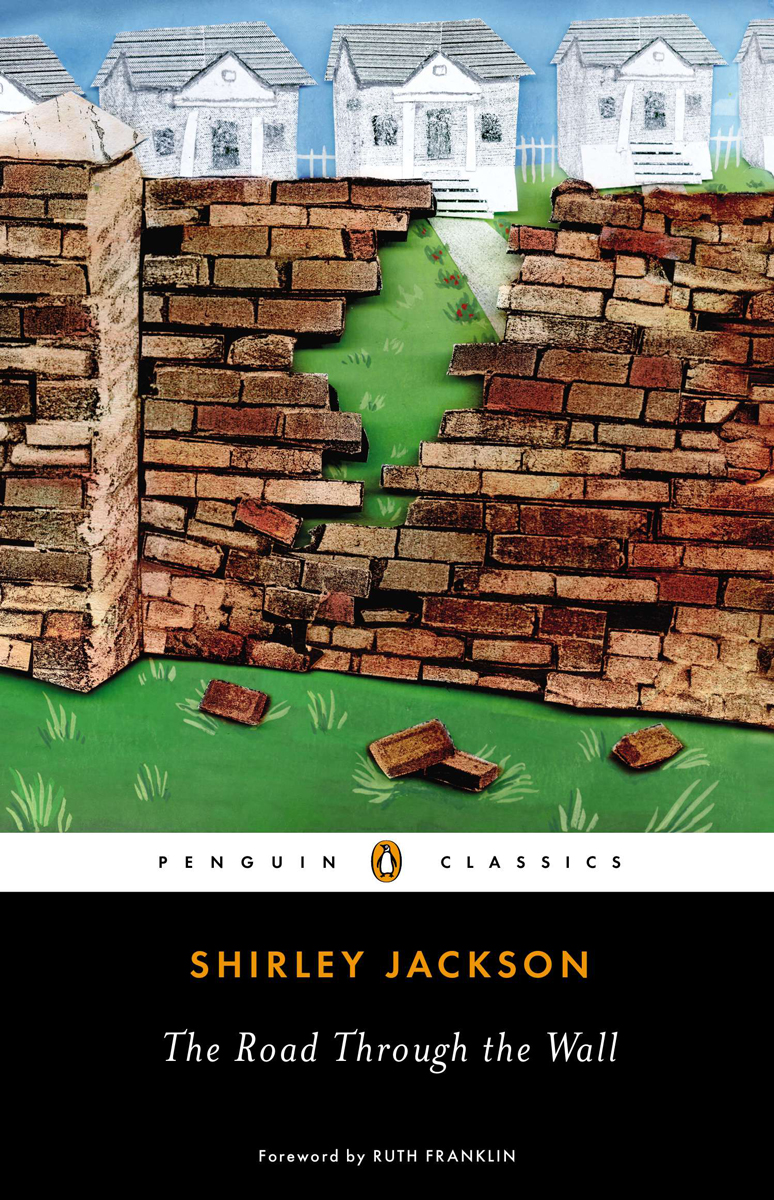

THE ROAD THROUGH THE WALL

SHIRLEY JACKSON

was born in San Francisco in 1916. She first received wide critical acclaim for her short story “The Lottery,” which was first published in

The New Yorker

in 1948. Her novelsâwhich include

The Sundial

,

The Bird's Nest

,

Hangsaman

,

The Road Through the Wall

,

We Have Always Lived in the Castle

, and

The Haunting of Hill House

âare characterized by her use of realistic settings for tales that often involve elements of horror and the occult.

Raising Demons

and

Life Among the Savages

are her two works of nonfiction. She died in 1965.

RUTH FRANKLIN

is a book critic and a contributing editor at the

New Republic

. Her writing also appears in

The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, Bookforum,

and

Salmagundi

. Her first book,

A Thousand Darknesses: Lies and Truth in Holocaust Fiction

, was a finalist for the 2012 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature. She is currently working on a biography of Shirley Jackson.

SHIRLEY JACKSON

The Road Through the Wall

Foreword by

RUTH FRANKLIN

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, USA

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

For more information about the Penguin Group visit penguin.com

First published in the United States of America by Farrar, Straus 1948

This edition with an introduction by Ruth Franklin published in Penguin Books 2013

Copyright Shirley Jackson, 1948

Introduction copyright © Ruth Franklin, 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this product may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author's rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Jackson, Shirley, 1916â1965.

The road through the wall / Shirley Jackson ; foreword by Ruth Franklin.

pages ; cm.â(Penguin classics)

ISBN 978-1-101-61678-9

I. Title.

PS3519.A392R63 2013

813'.54âdc23

2013005495

Contents

Foreword

“My goodness, how you write,” John Farrar wrote to Shirley Jackson after receiving the manuscript of

The Road Through the Wall

, her first novel. It was July 1947, almost exactly a year before the appearance of “The Lottery” in

The New Yorker

would make Jackson the most talked-about short story writer in America, but her career was already off to a promising start. The previous few years had seen nearly a dozen of her stories published in

The New Yorker

, as well as other respected magazines. After Jackson gave birth to her first child, a son, in 1942, the family relocated to Vermont so that her husband, the literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman, could teach at Bennington College. There Jackson began writing

The Road Through the Wall

.

Jackson once told her daughter Sarah that “the first book is the book you have to write to get back at your parents. . . . Once you get that out of your way, you can start writing books.” The parental crime to be avenged may have been simply the Jacksons' effort to provide their daughter with a typical suburban childhoodâto which she was by all accounts spectacularly unsuited. The novel is set in the fictional California town of Cabrillo, which bears certain similarities to Burlingame, where Jackson grew up: a middle-class suburb within commuting distance from San Francisco, with its majority-WASP population beginning to show the stress of an influx of newcomers, including Catholics, Jews, and Chinese. And certain incidentsâin the first scene, the protagonist, Harriet Merriam, comes home to discover that her mother has been reading her private writingsâmay be drawn from Jackson's life.

But it would be wrong to suggest that

The Road Through the Wall

is predominantly autobiographical. An ensemble novel with a large cast of characters, the book narrates the happenings on a single street from the perspective of a dispassionate onlooker. If it draws upon Jackson's experiences as a girl, it does so mainly to the extent that she was an uncommonly close observer who speculated, based on details real or imagined, that beneath the sunny surfaces of her neighbors' lives there lay darker secrets: infidelity, racial and ethnic prejudice, and basic cruelty.

The last point extends especially to the novel's children, who are treated with at least as much gravity as the adults and are well their equals in connivance and inhumanity. The story centers around Harriet's struggles to fit in with the other children on the block, and her short-lived friendship with Marilyn, another outsider. (Friendship between girls and women is a central theme in nearly all of Jackson's novels, and she is a particularly close observer of the small rituals by which these intimacies are created.) But Marilyn's family is Jewish, and the prejudice of the other neighborsâalways expressed subtly, in the politest termsâis unmistakable. When one family organizes the children on the block for a Shakespeare reading, for instance, they exclude Marilyn out of false concern that she will be offended by

The Merchant of Venice

. Finally, Harriet's mother tells her to break off their friendship. “We must expect to set a standard,” she says. “However much we may want to find new friends whom we may value, people who are exciting to us because of new ideas, or because they are

different

, we have to do what is expected of us.”

We have to do what is expected of us:

It is hard to think of a better definition of conformity. One of the novel's surprises is the essential role that women play in enforcing society's expectations.

The Road Through the Wall

exists almost entirely in the world of women and children: Nearly all the action takes place after the men have gone off to work. It would be a stretch to call it a feminist novel, not least because Jackson seems to have had an allergy to the word. Still, the way she portrays certain of her characters' attitudes strikingly anticipates the movement to come: One neighbor regards herself as “something more than a housewife,” and is scorned by the others for putting on airs. But no escape is possible from the hothouse of hostility in which these women exist. The psychological intrigues that dominate their lives turn out to be far from superficial: In fact, they have the power to bring down the neighborhood. Things start to fall apart not long after Harriet's rejection of Marilyn, and the pace of disintegration accelerates until the novel's disastrous conclusion.

The novel includes well over a dozen characters, but Jackson's control over her material is superb. She parcels out scenes in perfect rhythm, maintaining the book's taut atmosphere. Every description is carefully calculated for what it reveals, both about the character to whom it refers and the person whose attitude it represents. When Marilyn sneaks into the home of Helen Williams, the girl who is her chief tormentor, as the family is moving out, she notices the poor quality of the furniture and regrets having been so easily intimidated: “Helen dressed every morning for school in front of that grimy dresser, ate breakfast at that slatternly table . . . no one whose life was bounded by things like that was invulnerable.” Jackson's readers will recognize here the early flutterings of her interest in houses and their furnishings as expressions of psychological states: One unfortunate family lives in “a recent regrettable pink stucco with the abortive front porch . . . unhappily popular in late suburban developments.” (In an astonishing, almost throwaway aphorism, Jackson comments: “No man owns a house because he really wants a house, any more than he marries because he favors monogamy.”)

Compared to

The Haunting of Hill House

or

We Have Always Lived in the Castle

, Jackson's masterful late novels,

The Road Through the Wall

is a slighter work. But it is marvelously written, with the careful attention to structure, the precision of detail, and the brilliant bite of irony that would always define her style. There are wonderful moments of humor, as when one of the neighborhood girls, seeking to decorate her living room with some high-class art, accidentally orders a set of pornographic photographs. And the Merriam household is an all-too-convincing portrait of familial dysfunction. After Harriet's mother discovers her daughter's secret writings, she forces Harriet to burn them in the furnace while her father sits obliviously at the dinner table: “Seems like a man has a right to have a quiet home,” he grumbles to himself. Later Harriet and her mother will spend afternoons writing together: Mrs. Merriam writes a poem titled “Death and Soft Music,” while Harriet's is called “To My Mother.” A childhood poem in Jackson's archive bears a similar title.

The Road Through the Wall

was published by Farrar, Straus in January 1948 to a largely unappreciative audience. Critics were put off by the book's unpleasant characters, its grim tone, and its violent conclusion. But some recognized Jackson's inimitable gift for diagnosing the “little secret nastinesses” of the human condition. Jackson, it seems, was not discouraged by the reviews. At any rate, she was hardly dissuaded from using her fiction to tell her readers unpleasant truths about themselves. Those who were nonplussed by this first depiction of a small town in which the residents gradually undo one another must have been utterly astonished by the thunderbolt that came next. But for readers with the sense to take Jackson seriously from the start, “The Lottery” was a natural sequelâand a deserved vindication.

RUTH FRANKLIN