The Road to Berlin (12 page)

Read The Road to Berlin Online

Authors: John Erickson

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Former Soviet Republics, #Military, #World War II

Operations in the south were conceived as pursuit, designed to bring the armies of the Voronezh, South-Western and Southern Fronts to the Dnieper on a front reaching from Chernigov to Kherson by the time the spring thaw came. The

Stavka

directive of 6 February 1943 set the strategic objective of the Voronezh Front as the line Lgov–Glukhov–Chernigov (right wing) and Poltava–Kremenchug (left wing): this instructed Vatutin ‘to prevent an enemy withdrawal on Dnepropetrovsk and Zaporozhe’ and at the same time to ‘drive the Donets group of enemy forces into the Crimea, seal off the approaches at Perekop and the Sivash, and thus isolate the [enemy] Donets forces from the remainder of enemy forces in the Ukraine’. After the Donbas had been cleared, the South-Western Front would make for the Dnieper on a front running from Kremenchug to Nikopol, while Southern Front forces would invest the lower reaches of the river. Southwards, the ‘Rostov gap’, which the Germans were fighting fiercely to hold open, was slowly but surely closing. First

Panzer

Army was nevertheless well within sight of safety and coming under Don Army Group, while Army Group A fell back on the Kuban and into the Taman peninsula, all of 400,000 (with the two

Panzer

divisions, 50th and 13th, deflected in this direction) isolated from the main course of operations, though presenting some threat to the Soviet rear and also securing the defence of the Crimea. For these reasons, the Soviet command at the end of January prepared to assault Novorossiisk and to attack Krasnodar, operations timed to begin very early in February.

Vatutin’s South-Western command and Golikov’s Voronezh Front forces opened their major offensive operations within days of each other; Vatutin opened on 29 January, Golikov on 2 February 1943. The South-Western Front, embarked on the Donbas operations and a deep outflanking of Army Group Don from the west, comprised four armies (north to south: 6th, 1st Guards, 3rd Guards, 5th Tank), one air army (17th, with some 300 aircraft), a ‘Front mobile group’ under Lt.-Gen. M.M. Popov (four tank corps, three rifle divisions, two independent tank brigades and ski units, a total tank strength of 137 machines)—twenty-nine rifle divisions, six tanks, one mechanized and one cavalry corps, three independent tank brigades. On the morning of 29 January Kharitonov’s 6th Army jumped off north-west of Starobelsk aiming for Balakleya: the next day Lelyushenko’s 1st Guards struck from the south-west in the direction of Krasnyi Liman, and within a few hours Popov’s mobile formations were introduced between 1st Guards and 6th Armies, to drive south-westwards on an outward sweep aimed at Krasnoarmiesk–Volnovakha–Mariupol to slice the German escape route from the Donbas. V.I. Kuznetsov’s 3rd Guards Army on 2 February was over the Donets east of Voroshilovgrad. On that day also, in the great hole in the German line that gaped between Voronezh and Voroshilovgrad, at 0600 hours Golikov’s left-flank armies (40th, 69th and 3rd Tank Armies) attacked in the first phase of Operation

Zvezda

aimed at Kursk–Belgorod–Kharkov. 40th Army would attack in the general direction of Belgorod–Kharkov, outflanking Kharkov from the north-west, 69th was to strike directly at the city through

Volchansk and 3rd Tank (on whose left was Kharitonov’s 6th Army) would outflank Kharkov from the south-west. One new army had been raised on this front, on the basis of the 18th Independent Rifle Corps; the new formation, 69th Army, was assigned to M.I. Kazakov, with Maj.-Gen. Zykov (18th Corps commander) as his deputy. Like all the Soviet units, it was feeling the effect of the previous month’s strain, the troops far from fresh, with ranks depleted by ‘significant losses’ and with ammunition and supplies running low.

As Golikov’s left wing and centre attacked on the Staryi Oskol–Valyuiki sector towards Kharkov, Maj.-Gen. I.D. Chernyakhovskii’s 60th Army on the left drove along the Kastornoe–Kursk railway line with Kursk as its objective. Chernyakhovskii had divided his army into two assault formations, one with two rifle divisions and a tank brigade to outflank Kursk from the north, the other with a single rifle division to outflank from the south. Moskalenko’s 40th Army was under orders to be ready by 1 February to attack Belgorod and to drive on Kharkov, but by the morning of 3 Feburary only elements of the first echelon were at their start lines; the remaining units and formations, including the 4th Tank Corps, were still regrouping. Chernyakhovskii was well on the way to Kursk by 5 February. At 0900 hours on the morning of 3 February Moskalenko had committed the divisions he had assembled, but Kravchenko’s 4th Tank Corps was tangled up with encircled German units on the line of its movement, and was even further slowed as tanks ran out of fuel and ammunition. On the left, where Golikov had concentrated the main weight of his attack, and where Vasilevskii was supervising the co-ordination of the offensive against Kharkov, Rybalko’s lead tanks had reached the northern Donets by 4 February, though the presence of the

SS Panzer

division

Adolf Hitler

ruled out a crossing straight off the march. Rybalko would have to force a crossing in the Pechengi–Chuguev sector, with the high western bank firmly in German hands. Frontal attacks merely brought heavy losses in men and tanks, as well as fruitless expenditure of the limited quantities of ammunition. Not until 10 February did Rybalko manage to smash the resistance on his centre when Maj.-Gen. Kopstov’s 15th Tank Corps and Maj.-Gen. Zenkovich’s 12th Tank Corps took Pechengi and Chuguev, though a serious threat to Kharkov had already developed with Soviet outflanking movements to the north-east and south-west. Moskalenko’s 40th Army reached Belgorod on the ninth, when Kazakov’s 69th was through Volchansk; they then stormed across the ice of the northern Donets and within twenty-four hours were on the inner defensive line covering Kharkov, while away to the south-west the cavalry formations on Rybalko’s flank had swung through Andreyevka and were approaching Merefa.

Kharkov was a major prize, the second city of the Ukraine and the fourth largest in the Soviet Union, and Soviet troops were closing in on it at speed, putting the

SS Panzer

Corps and

Armee-Abteilung Lanz

at risk and bringing an even greater threat in their wake, tearing this time another great gap in the German ‘line’ between the southern formations and Army Group Centre. By

noon on 15 February, Soviet units closed on Kharkov from three sides, west, north and south-east. That night they were fighting inside the city. The

SS Panzer

Corps, right in the face of Lanz’s veto, pulled out of Kharkov and the danger of immediate encirclement, and on 16 February Kharkov was in Soviet hands, with a 100-mile breach torn open between what had been Army Groups B and Don (the latter redesignated Army Group South, taking over from the liquidated Army Group B and thus becoming immediate neighbour to Army Group Centre).

Throughout the first half of February, Vatutin had been steadily widening the scope of the operations of his right wing, moving across the Lisichansk-Slavyansk line and fanning out west and south, aiming at the Dnieper crossings. In two weeks, striking from the Starobelsk area, the right-flank formations—6th Army, 1st Guards and Popov’s armour (fourteen rifle divisions, two rifle brigades, four tank corps and three tank brigades)—were approaching Dnepropetrovsk and the Krasnoarmeisk area. The left wing (3rd Guards and 5th Tank Army) was fighting west of Voroshilovgrad (along the Nizhne Gorskoe–Astakhovo sector). To the south the Southern Front had finally closed the ‘Rostov gap’ by taking Rostovon-Don and was now pursuing

Armee-Abteilung Hollidt

as it fell back on the river Mius line. On the Soviet order-of-battle maps, the bulk of the 18 divisions of Army Group Don were identified on a line running from Slavyansk to Taganrog (that is, committed against Vatutin’s left flank and against Southern Front), but from Zmiev (south of Kharkov) to Slavyansk there gaped a mighty, 200-mile hole between

Abteilung Lanz

and First

Panzer

Army, with only the thinnest screen to hold it.

The prospect of amputating the German southern wing by closing off the Dnieper crossings looked dazzling. Northwards, at Kharkov, Golikov on 17 February issued formal orders for an advance on Poltava with Rybalko’s 3rd Tank Army in the lead. The General Staff had put Golikov ‘in the picture’ about developments with his ‘left neighbour’ (Vatutin) whose objective was now Dnepropetrovsk and asked Golikov what aid he could render. Golikov replied that the Voronezh Front would contribute support by striking at Poltava and Kremenchug with all speed. As for Vatutin, he decided to pile on the power of his offensive through 6th Army which would go first for Zaporozhe and then for Melitopol. Kharitonov’s 6th Army at this time consisted of two rifle corps (15th and 4th Guards), to which was attached a ‘mobile group’ formed up at Lozovaya out of two tank corps (1st Guards and 25th Corps) with one cavalry corps (1st Guards Cavalry)—in all, 150 tanks. Popov’s ‘Front mobile group’ with its four corps (4th Guards, 18th, 3rd and 10th Tank Corps) was now down to 13,000 men and 53 tanks fit for battle. Half the entire tank strength of the South-Western Front was out of action owing to battle damage or loss, and the tank units of Front reserve had exactly 267 operational machines between them. Now Popov’s ‘mobile group’, which had just lost almost 90 tanks in two days, was to attack in two directions—first towards Stalino and then on to Mariupol. Kuznetsov’s 1st Guards would meanwhile transfer part of its strength

to Kharitonov and Popov, holding the Slavyansk–Nizhne Gorskoe line with the remaining divisions; 3rd Guards and 5th Tank Army would press forwards to the west on Stalino, which troops of the Southern Front would also attack from the south-east. The race against time, against the weather, against depleted strength and stiffening German resistance was on, a furious fling to sew up the Donbas bag and to tie it off on the Dnieper.

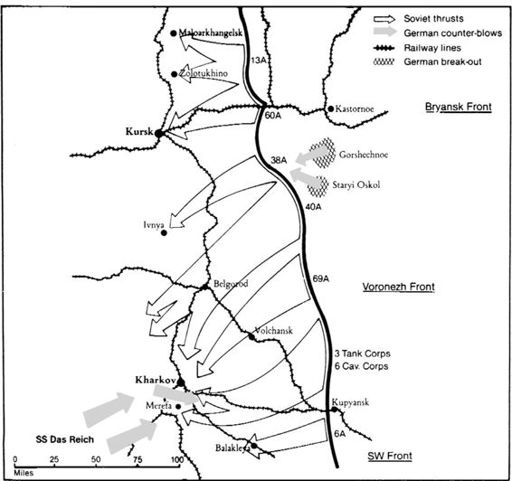

Map 3

The Soviet drive on Kharkov, February 1943

Vatutin had decided on this ‘broadening’ of his offensive on 12 February. Golikov had also set his sights on the Dnieper, even though his senior commanders, their divisions down to 1,000 men, a handful of guns and perhaps 50 mortars, pleaded for a pause. Both the Voronezh and the South-Western Fronts had done some prodigious fighting and covered great stretches of ground, following nothing less than a train of destruction as retreating German units blew up bridges, buildings and airfields, tangled railway lines and damaged the few roads as much as possible. Both Vatutin and Golikov, however, embarked on an expansion of

their offensives as a result of three factors: overestimation of their own capabilities, wholly erroneous interpretation of the intelligence of German movement and

Stavka

approval. Vatutin had already dipped deeply into his reserves. Golikov overrode his commanders when they pointed to their present drastic shortages—the two tank brigades (88th and 113th) of 3rd Tank Army, for example, had only six tanks between them. Both Front commanders supposed that they would be mainly conducting the pursuit of a retreating enemy to the Dnieper, and for this their forces were certainly adequate.

The movement of German tanks and motorized formations had been duly observed, but it gave little cause for alarm. South-Western Front intelligence reports for the period 10–26 February, countersigned by the chief of staff Lt.-Gen. S.P. Ivanov and the senior intelligence officer Maj.-Gen. Rogov, recorded German concentration in the Krasnodar and Krasnoarmeisk area after 17 February, but concluded that this was an attempt to clear the German lines for ‘a withdrawal of troops from the Donbas to the Dnieper’. Vatutin himself shared this view, though when he used it to justify further extensions of offensive operations, Popov (deputy Front commander) and Kuznetsov (1st Guards) objected forcefully. Golikov on the Voronezh Front was similarly beguiled; enemy forces that had pulled out of Kharkov and which were also concentrated at Krasnograd, to the south-east of Poltava, must be withdrawing on Poltava itself, probably to defend the river Vorskla line. No major enemy force in Poltava showed itself, nor any rail or road movement from the west. Intelligence reports from partisans and agents produced nothing to contradict this picture. On 21 February, Stalin ordered the deputy chief of Operations (General Staff), Lt.-Gen. A.N. Bogolyubov, to establish exactly what was happening in the Donbas. The staffs of the Voronezh and the South-Western Fronts, as well as General Staff Intelligence, all presently shared the same view (because they shared the same information) that German troops were pulling back to the Dnieper. From Maj.-Gen. Varennikov, chief of staff to the Southern Front, Bogolyubov learned that, ‘according to precise information, yesterday [20 February] solid enemy columns were pulling out of the Donbas’.

All three Soviet fronts had substantial intelligence of German movement. On the afternoon of 19 February and at dawn on 20 February Soviet reconnaissance planes reported large concentrations of German armour in the Krasnograd area, troop movements on Dnepropetrovsk and what looked like armour regrouping to the south-east of Krasnoarmeisk. These concentrations—lying slap across the path of Vatutin’s right wing—were immediately interpreted at Front

HQ

s as German tank cover for the withdrawal of the main body of German forces from Donbas. At 1600 hours on 20 February, Lt.-Gen. S.P. Ivanov, Vatutin’s chief of staff, signed an operational appreciation which affirmed that German armoured movements—the tank columns of divisions from XLVIII

Panzer

Corps observed by Soviet reconnaissance planes on the 70-mile sector between Pokrovskoe and Stalino—were proof positive of

continued withdrawal

from the Donbas on

Zaporozhe. The wish was father to the thought. For this reason, Kharitonov’s orders to advance remained unchanged on 20 February, while the day before Vatutin had expressly ordered Popov and his ‘Front mobile group’ to press on with all speed, though Popov’s tank strength was dwindling daily and he had little in the way of supplies.