The Road to Berlin (134 page)

Read The Road to Berlin Online

Authors: John Erickson

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Former Soviet Republics, #Military, #World War II

Meanwhile Bunyachenko in a remarkable exercise of generalship, determination and low cunning marched southwards, standing his ground against Schörner who threatened to have him shot; skirting German units, or slipping through them—at one point striding right across them—Bunyachenko eluded Schörner, kept the 1st Division out of the battle line and, towards the end of April, by dint of some ferocious forced marching crossed the Czechoslovak frontier. Suddenly Field–Marshal Schörner in person descended on the 1st Division, enquired about its battle readiness and abruptly left Bunyachenko and his 25,000 men to their own devices. While the 1st Division encamped north of Prague, another

KONR

force—2nd Division—pulled out of southern Germany, passed through Austria and also made for Prague, taking up positions to the south of the city. Here they might perhaps await the arrival of American troops.

Almost as soon as he arrived near Prague, Czech partisans sought out Bunyachenko and made him privy to their plans for an armed uprising in Prague: could they count on the 1st Division in this eventuality? While Bunyachenko saw some honour—and some hope—in this venture, other

KONR

units tried to

rescue themselves as best they might from a nightmarish situation; the

KONR

‘Air Corps’ managed to make contact with the Americans and received honourable treatment at the hands of General Kennedy. Others, their numbers running into many thousands, found no such response and were abandoned—or worse, forcibly handed over—to horrible Soviet retribution. Vlasov sent out his own emissaries in an attempt to make contact with the American authorities, waiting out the hours for a reply in his temporary headquarters at Kosojedi near Prague and witnessing the baleful erosion of relations between the Vlasovite Russians and the Germans. He had been instrumental in staying Schörner’s hand levelled yet again at Bunyachenko, whose 1st Division had now moved to Beroun south-west of Prague. Schörner gave up his nominal hold on the 1st Division, the German military hoping at least for the neutrality of the

KONR

troops, but to Vlasov’s shock his Russian troops were taking matters into their own hands and cutting down German soldiers, a base betrayal of honourable allies in Vlasov’s view. Back in his own headquarters Vlasov confronted Bunyachenko over the issue of supporting the Czech insurgents and breaking openly with the Germans. Bunyachenko advocated supporting the Czechs and turning on the Germans, an act which the Czechs would repay within their new-found state by affording shelter to the

KONR

men. Vlasov disputed this violently, arguing that breaking with the Germans would be odious treachery aimed at German soldiers who had at least kept their word, while assisting the Czechs could avail little or nothing since the Red Army would soon be in Prague. Bunyachenko waved this aside, asserting that the Germans deserved their fate and

KONR

commanders must now act to save their men, a view supported vehemently by other officers of the 1st Division. Vlasov could do no more.

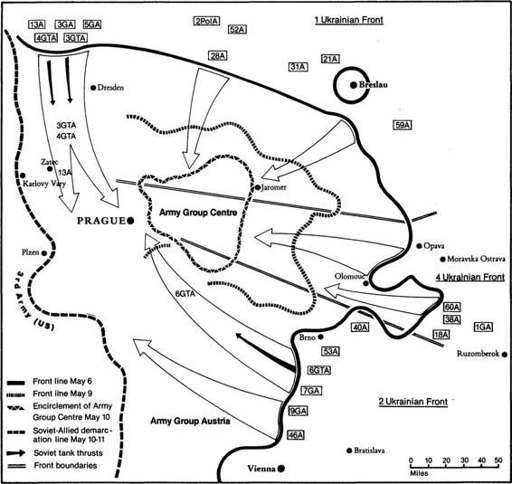

On 4 May, at about the time of this confrontation between Vlasov and Bunyachenko, Marshal Koniev summoned his army commanders to a conference. His attack orders had already been issued at 0110 hours that morning and now he added a personal briefing on the forthcoming Prague operation. He planned to launch three attacks: on the right flank north-west of Dresden, three rifle armies (3rd and 5th Guards, 13th Army) with the two tank armies (3rd and 4th Guards), reinforced with two tank corps and five artillery divisions, would strike along the western bank of the Elbe and the Vltava, developing the attack in the direction of Teplice–Sanow–Prague, thus partly enveloping the Czech capital from the west and south-west; a second attack would unroll from the area north-west of Görlitz with two rifle armies (28th and 52nd) advancing towards Zittau–Mlada Boleslava–Prague. A third attack was assigned to the 2nd Polish Army in order to outflank Dresden from the south-east, though Zhadov’s 5th Guards Army was entrusted with the actual reduction of Dresden. Koniev gave explicit orders that the tank armies were not to become bogged down in the fighting for Dresden, impressing on Rybalko and Lelyushenko the need for the utmost speed during the first two days of the offensive—after the punishing battles of the Dukla pass Koniev had little taste for fighting in mountains and therefore he wanted the Krusnehory mountains ‘vaulted’ with all possible speed. All armies, save for 28th and 52nd, must be ready to jump off by the evening of 6 May.

Map 16

The Soviet drive on Prague, May 1945

General Eisenhower also reviewed his plans at this time, deciding finally that once the Karlsbad–Pilsen area had been secured an advance to the Vltava—and thus to Prague—was now both feasible and desirable. The Supreme Commander duly notified General Antonov, Chief of the Soviet General Staff, of this decision, only to receive a sharp reaction from the Soviet side, ‘requesting’ that Allied forces should not move east of the designated line—after all, had not the Red Army earlier halted its own advance on the lower Elbe at General Eisenhower’s

specific request? Marshal Koniev underlined the point on 5 May when General Omar Bradley visited the headquarters of 1st Ukrainian Front. In answer to a question about possible American help for the Prague operation, Koniev insisted that no help was necessary and that to avoid ‘muddling things up’ US troops should keep to the demarcation line. The road to Prague was definitely and deliberately barred.

Unaware of this profound change in the situation but excited by news of the American advance into Bohemia, the citizens of Prague took to the streets in sponaneous fashion on the afternoon of 4 May, tearing down German street signs or daubing them with patriotic slogans. Radio Prague under German control thundered out threats of reprisals combined with orders to desist, but the street demonstrations continued. Such was the speed, spontaneity and extent of this mass demonstration that the insurgent planners were taken by surprise and their carefully nurtured schemes for an organized rising thrown into disarray. The Czech resistance movement counted both Communists and nationalists within its ranks, with the former compensating for their lack of numbers by superior organization; for all practical purposes the rising had already begun, though it had been timed originally for 7 May. On the morning of 5 May (at 11.38 am local time) Prague Radio broadcast a dramatic appeal, urging all Czech police, all Czech soldiers, all Czechs to report to the radio station—‘We need help!’ The population, once more on the streets, set to work with a will building barricades, tearing up cobblestones and pushing trams over to block roads and avenues. The National Council

(Narodny Rada)

met in hurried session, voting to a man to lead the rising in spite of the absence of the air-drop of arms which the British had earlier promised—the rumours that the aircraft had already left Bari proved to be false, as were the reports that General Patton’s tanks were only mere miles away from Prague.

This beautiful unscarred city, so far unhurt by bombing and not yet pockmarked by artillery fire, prepared to make war. The radio continued to direct the insurrection, announcing the proclamation of the National Council at 6.15 pm on the evening of 5 May that Greater Prague had been taken; ten minutes later, Station ‘Prague, Czechoslovakia’ instructed the population to set up barricades along the road from Benesov to Prague because German tanks were starting to move towards the city. In English and Russian, Station ‘Prague, Czechoslovakia’ also broadcast an appeal for air support in order to hold off the German armour.

Listeners to ‘Station Prague, Czechoslovak Radio’ had already learned that the National Council had assumed the direction of the rising. Hurriedly convened and struggling to control a confused situation, the Council selected Professor Albert Prazak as its president, with Josef Smirkovsky as his deputy and representative of the communist minority. Titular military command went to General Kutlwasr, though the Czechoslovak government in London at once dispatched Captain Nechansky as its own military nominee and delivered him to the scene in a parachute drop. The initial German reaction was slow and almost half-hearted,

with troops and police trying to chase off the demonstrators, but the

Waffen SS

gathered its strength to strike back with customary ferocity. Towards ten o’clock on the evening of 5 May ‘Station Prague’ announced that the

Protektorat

and the German administration no longer existed and that the National Council held many of these men prisoner. But at 0053 hours on 6 May the assuredness of this tone was shattered by a frantic call to the US Army—‘Send your tanks, send tanks and aircraft. Help us save Prague’, repeated in a broadcast transmitted in Russian and English an hour or so later announcing the German encirclement of Prague—‘Prague needs help. For God’s sake help!’ At 0210 hours ‘Station Prague’ sent out one particular signal to Lt.-Col. Sidorov of the 4th Department, Commissariat for State Security in Kiev: this plea in Russian urged both the dispatch of air cover and parachutists who could be dropped on the Olsany cemetery in Prague. Throughout the night more appeals went out by radio, begging for help and asking for confirmation of receipt. The

BBC

replied, Soviet transmitters remained silent.

Another broadcast in Russian went out at 0328 hours but addressed this time to ‘Vlasov’s Army’ rather than the Red Army. The Czechs appealed to the Vlasov troops ‘as Russian and Soviet citizens’ to support the rising in Prague. Bunyachenko with his 1st Division kept close contact with the staff officers of the Czech insurrection and knew now that the National Council had assumed political responsibility for the operation in Prague. The issue of Bunyachenko’s active participation—since 1st Division was the crucial military counterweight in this situation—brought dismay to the Germans and confusion within the Czech ranks. A Czech broadcast on the evening of 6 May stated exuberantly that not only were Allied divisions on the way to Prague but that ‘General Vlasov’s units arrived here today’, countered in turn by an appeal from the German command broadcast in Russian shortly after midnight on 7 May to the Vlasov troops, ‘first allies of the German people in its heroic struggle against Bolshevism’, not to desert the German cause. Further discouragement for the ‘Vlasov army’ came from a somewhat unexpected quarter, from the Czechoslovak government in London, one of whose ministers—Dr Ripka—advised his compatriots in a broadcast that they should shun ‘help from traitors’ and refrain from staining the escutcheon of anti–German resistance by association with ‘Vlasov traitors’.

Bunyachenko’s troops had already lent considerable aid to the insurgents, ignoring German pleas and responding to the appeal of the National Council. Taking on the

Waffen SS

, the 1st Division hammered its way into the city and occupied the aerodrome, the radio station and other key positions; in the early hours of 7 May (at 0507 hours) Vlasov made the break complete and called on German troops in Greater Prague to surrender unconditionally or else face annihilation. Brave words these and substantially justified, but a shock awaited Bunyachenko that morning: having assumed he was operating with the cognizance of the National Council, Josef Smirkovsky informed him that the political authority of the Council did not extend to the

KONR

, the Council would have nothing

to do with traitors and mercenaries—moreover, many men of the Council were Communists, the Vlasov men were declared enemies of Communism and thus became enemies themselves.

As if by magic, however, three US Army vehicles had reached the suburbs of Prague, a harbinger which Prague Radio announced as the prelude to a full-scale advance by American and British troops. But the trickle never became a flood, since observance of Soviet stipulations brought all troops back behind the Pilsen line, a shattering revelation which caused Bunyachenko to think at once of a speedy withdrawal and possible salvation at the hands of the Americans. The German command was equally confused and as intent on flight as the Vlasov men. The fighting in the city had all but died away by the night of 7 May, leaving German units—and the

KONR

—ensnared by Czech barricades and harried by partisan groups. In a bitter renewed brotherhood of arms Bunyachenko’s men and the

SS

again closed ranks to punch their way through Czech cordons and fight their way free of a fate both dreaded above all else, capture by the Red Army.

During the night of 7–8 May the National Council and the German command talked their way towards a form of agreement, announced at 0504 hours on the morning of 8 May as the unconditional surrender of German forces in Prague. Bunyachenko was pulling back on Beroun and making ready to march south with all haste. Lacking real information about Bunyachenko’s plans to aid the Czechs, the command of the

KONR

2nd Division and General Vlasov’s Chief of Staff, Fedor Trukhin, had already opened negotiations with the Americans and were ordered to pass over to the American lines, lay down their arms and surrender within thirty-six hours. News of this was sent to Bunyachenko but no reply came: first Boyarskii and then Trukhin set out in search of Bunyachenko, only to encounter a Czech partisan unit in Pribram—with a Red Army captain in command. Boyarskii was hanged on the spot, Trukhin consigned to the Red Army. Blagoveshchenskii, sent out to search for Trukhin, also fell headlong into this Red Army death-pit. These were among the first of many thousands to be bludgeoned, hanged, shot, bestially tortured, transported to slave camps or forced to suicide, all in the name of the fair principle of ‘repatriation’.