The Road to Freedom (14 page)

Read The Road to Freedom Online

Authors: Arthur C. Brooks

Here are two false “facts” that we often hear: (1) compared to other countries, America does not tax corporations heavily, and (2) America has a lightly regulated economy. Both are false.

Let's start with corporate taxes. The U.S. top combined statutory corporate tax rateâwhich includes both federal and (average) state taxesâwas 39.2 percent in 2011, the second highest in the industrialized world, next only to Japan.

26

Until the late 1980s, corporate tax rates in the social democracies exceeded America's. At that point, virtually all of the U.S. competitor nationsâeven the most socialist democracies such as Swedenâbegan to find that in order to prosper in a global marketplace, penalizing entrepreneurship in this way was unwise. To attract business, their business income tax rates began to fall. The United States lowered its top rate one time (in 1986), but never again. The U.S. even raised its top rate by 1 percentage point in 1993. Around 1990, the industrialized world average dropped below that of the U.S., and the gap has gotten wider ever since. Today, Sweden's effective corporate rate is 13 percent lower than America's.

27

The story about regulation has followed the same pattern. Regulation has gradually increased the cost of entrepreneurial activity since about 1960. Two Lafayette University professors have calculated the current total burden of regulation on the U.S. economy, in terms of the cost of compliance.

28

They found that in 2008, the regulatory burden was $1.75 trillion. That was 12 percent of GDPâ18 percent larger even than 2012's record-busting government budget deficit.

29

The burden of regulation is especially high on small businesses, traditionally the job creators, and America's means of recovery

from a national recession. In 2008, just adhering to federal rules cost businesses with nineteen workers or fewer $10,585

per worker

. That's how much value workers need to create before employers break even and can afford to pay the first dollar in wages. Looking at the regulatory burden per employee is especially useful because it gives an idea of the drag government puts on job creation. According to one study, the burden increased by 21 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars from 2000 to 2008.

30

No wonder economists are finding that the U.S. economic recovery is so slow. Small businesses aren't hiring because it simply costs too much.

To get an idea of how much more regulated Americans' lives and the economy are today compared with the past, consider the growth in the workforce of federal regulatory agencies. In 1960, there were about 57,000 employees in this sector. Today, there are about 292,000. In 2000, the number of regulators per billion dollars of GDP was sixteen. Today, it is twenty-one.

31

So the regulatory environment is increasingly onerous, and the U.S. taxes business more than the European countries do. This is not encouraging, if we seriously think we can avoid Europe's economic fate.

.

What do Mark Twain, P.T. Barnum, and Oscar Wilde have in common? They were all wealthy people who went bankrupt. There are many similar stories: A rich celebrity lives more extravagantly than he can afford, and goes bust. Reading about his situation, you are filled with a little bit of

schadenfreude

, and a big dose of contempt. All that money, you think, and still he racked up ruinous debt. He's irresponsible.

Look in the mirrorâhe is you, my fellow American. As of December 2, 2011, Americaâthe richest nation in the history of the worldâowes its creditors $15,101,125,095,514.72.

32

To put that into perspective, that's $48,290 for every American, which the U.S. will either have to pay back or default on if it goes bankrupt like so many other countries throughout history.

When faced with this problem in Great Britain in the 1980s, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher is reported to have said that the problem with socialism is that eventually you run out of other people's money. That's the road America is headed down now.

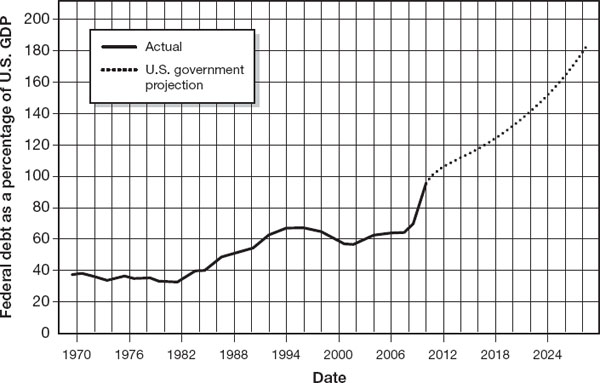

When did the binge begin? Back through history, there have been many periods of high debt, often correlated with periods of war. Eliminating those, the modern peacetime debt increases started around 1982 in America, when Ronald Reagan's defense buildups were not paid for by reducing domestic spending. Debt leveled off and decreased somewhat through the late 1990s and early 2000s, but then exploded back up to their highest levels ever, starting in 2009.

According to the Congressional Budget Office, today, our debt-to-GDP ratio is about 100 percent. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimates that by 2015 federal debt will reach 113 percent of GDP. By 2030, debt will be 194 percent of GDP.

33

Social democracies cater to the voters by lavishing government services on themâthat's their lure. Naturally this means focusing on the current generation's wants with little regard for future generations, because future generations' voters and politicians are voiceless. The inevitable result is that governments can and do begin to borrow from the futureâcreating the debt we see all across Europe, and increasingly right here at home.

This is not just unsustainable, foolish, and a sign of irresponsibility and poor national impulse control. It is theft from our children, and it is immoral.

Figure 5.5

. Federal debt is rising quickly as a percentage of GDP. (Source: Author's calculation using Congressional Budget Office 2001 Long-Term Budget Outlook Alternative Fiscal Scenario,

http://www.cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index=1221

)

Social democracies sacrifice robust economic growth for a strong welfare state and income equality. This statement is not controversial. Every serious economistâleft or rightâknows it to be true. According to an economist with the United Nations' International Labour Organization (ILO), there is a “tradeoff” that people experience “when a society has to sacrifice economic growth to achieve a reduction in inequality.”

34

Swedish economists Andreas Bergh and Magnus Henrekson have measured the negative relationship between government spending and economic growth. In a large survey of the economics literature, they found that a 10 percent increase in government spending corresponds to a decrease in economic growth of between 0

.5

and 1 percentage point. In other words, if the U.S. is

now growing at 2 percent per year and the federal government spends an extra $400 billionâa 10 percent increase in federal spendingâexpect to see economic growth move from two percent to about 1.5 percent, or even lower.

35

Some say that it is necessary to grow government for the sake of creating jobs. But this is the reverse of the truth, according to most economists who have studied what happens to the private sector when the public sector grows. Studies vary in their conclusions, finding that every government job created eliminates between 1 and 2.2 private sector jobs. In other words, the labor effect of government growth is in the best case neutral, and in the worst case hugely destructive.

36

Given the evidence about increases in the size of government, regulatory growth, and ballooning debt, lower economic growth over time in America is fairly predictableâand clearly present. During the 1950s and '60s, average annual growth was more than 4 percent. In the 1970s, '80s, and '90s, it was a bit over 3 percent. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, the average was 1.6 percent. The average over the last three years has been 0.1 percent.

37

We all hope the weak growth from 2008 to the present is an historical outlier because of the recession. But we can't dismiss a broader trend: For at least fifty years, when we smooth out all the ups and downs over the business cycle, America's growth has been generally falling.

38

Few if any economists, no matter their political views, dispute these basic trends; the data are the data. Differences in opinion only come in when we ask, “Who cares?” The social democratic position is that low growth is a cost of a comfortable, enlightened society. Basically, America is rich enough. Why go crazy trying to grow at high rates? Leave the rat race behind. Invest in social welfare. Live a little.

Figure 5.4

. Economic growth in America has fallen for five decades. (Source: “National Economic Accounts: Gross Domestic Product,” Bureau of Economic Analysis, data,

http://www.bea.gov/national/index.htm#gdp

.)

I encourage you to reject this viewpointânot because you or I necessarily need to get richer, but because there are still plenty of people in our midst who do not share properly in the economy's bounty. Only strong growth will create the ecosystem to lift up whole nations and future generations.

Chapter 4

showed that free enterprise's unparalleled ability to create wealth ended poverty for many millions of our own citizens and billions more around the world. This would not have occurred had we imposed policies that limited U.S. economic growth to 1 or 2 percent. It's not about

us

. It's about the

poor

. Social democracy pulls the economic ladder up behind us.

ADDED

up, the evidence is clear: America has already effectively slipped into a big government social democracy. About 40 cents of every dollar Americans earn goes to the state. The government

has spent a good chunk of future generations' income too, equivalent to an entire year's GDP that they will have to pay back in the future. What about all the talk of the U.S. being “different” than the European countries? It may be true on a philosophical level, but it's not accurate when based on what the U.S. government is actually doing today.

All this is great news for those who have a European view of the role of government and do not believe free enterprise is the best system to support the U.S. culture and economy. But massive debt, stagnant growth, and high unemployment are not the American Dream for most. So it's the job of free enterprise advocates to propose an alternative model to the status quo. That starts with a practical philosophy of government, which I turn to now.

T

HE

G

OVERNMENT

W

E

W

ANT:

U

NCLE

S

AM, OR

U

NCLE

S

UGAR

?

I

once took a private tour of the National Palace Museum in Taiwan. This museum contains some of the most exquisite works of Chinese art in the world, transported out of mainland China in 1949 just before the country's fall to Mao Tse-tung's communists.

Almost everybody recognizes big visual differences between Western and Eastern art. I always wondered if these differences went beyond materials and technique, thoughâwhether there was some fundamental philosophical distinction between the Western art I had been surrounded with all my life and the artistic treasures of the East. I used the opportunity that day in the museum to ask my guide what this distinction might be.

In the West, he told me, we see a blank canvas as empty, and ready to be filled up through the artist's inspiration. A painting does not exist until the artist loads the canvas with color and images.

In the East, artists don't think of creating something from nothing. They start with the belief that the finished work already exists, and simply needs the excess parts stripped away. The easiest way to understand this is not by thinking of an artist's canvas, but rather a block of stone to be sculpted. Before the artist begins, the finished sculpture exists within the block. The artist's job is to chisel away the parts that are not part of the sculpture.