The Road to Freedom (7 page)

Read The Road to Freedom Online

Authors: Arthur C. Brooks

Many Americansâperhaps youâdisagree with the claim that fairness requires less income inequality. They think that higher taxes may be necessary for the countryâor not. But either way, redistribution does not make society “fairer.” That's because they prefer the second definition.

The fact that there is more than one definition of fairness led the great Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman to write that “âfairness' is not an objectively determined concept. âFairness,' like âneeds,' is in the eye of the beholder.”

8

Many economists have taken this to mean that people should dismiss the whole concept of fairness and ignore it as hopelessly subjective, even childish, like the argument between my kids.

This is a mistake. To dismiss fairness is like dismissing

love

: a difficult phenomenon to identify quantitatively, but a central facet of life and hugely important to nearly everybody.

THE REAL QUESTION

is not

whether

fairness mattersâit doesâbut

which definition is correct for public policy

. Is it equal outcomes, rewarding merit, or something in between? Social scientists over the years have developed experiments and surveys that help answer this question.

One fairness experiment is called an “ultimatum game.” Two subjects who don't know each otherâimagine they're you and

meâare asked to split a certain amount of moneyâsay, $10. I am given the $10 and am instructed to choose how much to offer you. I offer you $3 and keep $7. Next, you are told to accept or reject the offer. If you accept, we both keep the respective amounts. If you reject the offer, we both walk away empty-handed.

Classical economic theory predicts that you should accept any positive offer I make. If I offer you a penny and propose to keep $9.99, you'll take it because it's better than getting nothing, according to the theory.

But, of course, that's wrong. If the offer seems too unfair, you'll walk away out of spite and punish me for my selfishness. In the United States, games like this have an average offer of about $4. People reject the offer between 9 and 17 percent of the time.

9

When the ultimatum game is played in various other countries, the results differ significantly. Researchers observed the highest offers in Paraguay, where good-hearted Paraguayans offered grateful partners a bit more than half, on average. They observed that the lowest offers were in Spain, about $2.50, on average. Not coincidentally, Spain has the highest offer-rejection rate, approaching 30 percent. (According to my Spanish wife, this explains some of the problems in doing business in Spain.)

Just for fun, I tried the ultimatum game using my three kids as subjects. My two sons (ages eleven and thirteen) and my daughter (age eight) each got to play on both sides of the game with the other two, using ten pieces of candy in each round.

10

The big winner was my daughter.

11

She made generous offers to my sons, got generous offers in return, and suffered no rejections. She ended up with eighteen pieces of candy. My sons made miserly offers to each other, which each summarily rejected with great prejudice. Their haul of eleven pieces each came entirely from good trade relations with their little sister.

In the ultimatum game, merit is not part of the experiment. Nobody earns the resources they are bargaining over. You walk into the room, and somebody gives you ten bucks (or ten pieces of candy). That's it. Under these circumstances, participants find it unfair to try to keep too much. That's why they are willing to reject offers in order to punish others, even when it means personal sacrifice. Fairness matters to people, even in little experiments.

When merit comes into the mix, however, people's perceptions change a lot. If you

earn

what you have, most people think you have a right to keep it, even if others end up with less.

There are no ultimatum games using earned income, but there are surveys that show the same thing. For example, in 2006, the World Values Survey asked a large sample of Americans to consider this scenario:

Imagine two secretaries, of the same age, doing practically the same job. One finds out that the other earns considerably more than she does. The better paid secretary, however, is quicker, more efficient and more reliable at her job.

12

Then the survey asked, “Is it fair or not fair that one secretary is paid more than the other?” To this question, 88.6 percent answered that it was fair to pay the better secretary more, while 11.4 percent said it was unfair.

So which is the “right” definition for American public policy: redistributive fairness or meritocratic fairness? The answer is, “it depends.” When people do not perceive resources to have been earned (as in the ultimatum game), they think it fair that the resources be split somewhat evenly. When merit is involved (as

in the case of the two secretaries), people believe that unequal rewards are fairer than equal rewards.

When I was a university professor, I used to make this point to my economics students in an unorthodox way. There was always a lot of class discussion about how society should distribute income. Many of the students were politically progressive, and I probably heard them say a thousand times that it is “not fair” the rich in America have so much more than the poor.

Fairness

was their rationale for income redistribution.

So I set up a thought experiment. Halfway through the course, I could see big differences between students who were working hard and those who weren't. The hard workers got lots of points on their tests and quizzes; their less motivated friends didn't. We all knew that the students with the highest point totals were working harder than the others. They might have been a bit brighter or already knew more about economics, but the

real

difference was how much they were studying.

I proposed that the class take a quarter of the points earned by the top half of the class and pass them on to the students in the lower half of the class. The students were in unanimous agreement that this was a stupid idea. Redistributing points earned on the basis of hard work and merit, simply so that students who didn't study could get a higher grade, would be completely unfair. Even students at the bottom thought the scheme was idiotic.

I didn't have to spell out my point. Beyond providing for essential services and a minimum safety net, redistributing earned income just to get more equality is not fair.

If income were handed out purely arbitrarily, then most of us would viscerally agree that the money should be redistributed in a more-or-less equal way. But income is not handed out to people purely arbitrarily. Most of us believe that even if the system is

imperfect, we earn our success through hard work and initiativeâin a word, through

merit

. Most of us understand that some redistribution is necessary to pay for a functioning government. But relatively few believe that the resources people earn should be redistributed to help equalize outcomes.

THE UNITED STATES

was founded on the ideals of meritocratic fairness. Alexis de Tocqueville wrote that Americans are “contemptuous of the theory of permanent equality of wealth.”

13

Thomas Jefferson famously said it in this way:

To take from one, because it is thought his own industry and that of his fathers has acquired too much, in order to spare to others, who, or whose fathers, have not exercised equal industry and skill, is to violate arbitrarily the first principle of association, the guarantee to everyone the free exercise of his industry and the fruits acquired by it.

14

The views of Tocqueville and Jefferson follow an ancient truth: that to take resources from those who legitimately earn them and give them to another who does not is not fair. If it is voluntary, it is charitable. But if it is coerced, it is

un

fair. Aristotle put it best: “The worst form of inequality is to try to make unequal things equal.”

Following in the footsteps of the Founders, Americans prefer rewarding merit over redistribution. Public opinion studies show this, such as the one about the two secretaries. Still, a lot was left to the imagination in the story of those two secretaries. Did they

both have access to a good education? Had both received equivalent training for the job? For their unequal salaries to translate into a fair economic system, both the secretaries needed the opportunity to develop their abilities. It's not so fair, for example, if the less effective secretary couldn't go to school and didn't know how to read.

If individual opportunity is a shamâif the system is fixed and some people get the breaks only by virtue of luck or birth or skin colorâthen inequality isn't fair at all. We should redistribute wealth the same way we should redistribute unearned candy.

15

But if America is an opportunity societyâif, in fact, people have the chance to work harder, get more education, and innovateâthen rewarding merit is fair, and for some people to make more money than others is good and just.

The real question, then, is whether America is an opportunity society. If it is, then inequality is fair. If it isn't, then inequality isn't fair.

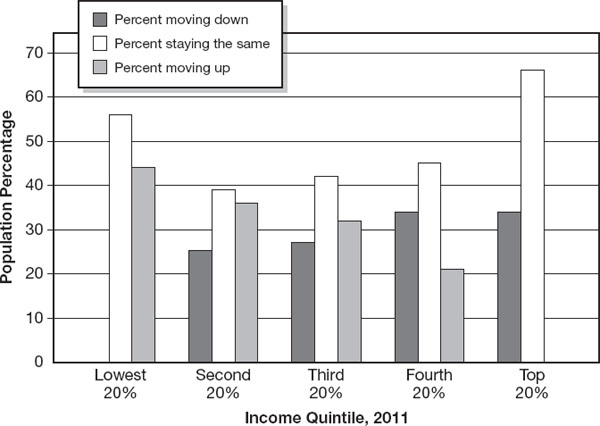

According to the evidence, the United States is an opportunity society, even if an imperfect one. One way to show this is by looking at whether people can and do get ahead economically. University of Michigan-Flint economist Mark Perry has analyzed data from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis to see whether Americans are mobile between income classes. He asked the questions, “If you're poor in America, does this mean you'll stay poor? And if you're rich, are you set for life?”

16

The answer to both questions was a resounding no. The poor can and do rise in America, according to Perry's research, and the rich can and do fall. He shows that 44 percent of households in the bottom income quintile (the lowest 20 percent of earners) in 2001 had moved to a higher quintile by 2007. During the same period, 34 percent in the highest quintile in 2001 moved to a lower quintile by 2007. In other words, if you are poor, the chances are about one in two that you'll be doing better within a few years. If you are at the top, the chances are about one in three that you won't stay there very long.

Figure 3.1

. Starting out poor or rich in America is no guarantee of staying that way. (Source: Mark Perry, “Income Mobility in the Dynamic U.S. Economy,” 29 March 2011

, The Enterprise Blog,

http://blog.american.com/2011/03/income-mobility-in-the-dynamic-u-s-economy

.)

Perry's results are typical. Economists at Urban Institute (a center-left think tank) conducted a large survey of the studies on income mobility in America, concluding that “mobility is significant and has remained stable over time.”

17

Using the University of Michigan's Panel Study of Income Dynamicsâthe most comprehensive nonpartisan data source tracking people and their incomes over the decadesâeconomists have found that the likelihood of escaping the bottom quintile in a ten-year period is 44 percent.

18

Another study using the same data found that the escape rate over five years is 38 percent.

19

Not everybody rises from poverty, but millions and millions do. This means real people in America are experiencing real opportunity, all the time. For them, the American Dream is no illusion.

I am not arguing that everybody has an equal chance to rise. A lot of people are stuck at the bottom, especially if they have gotten an inadequate education, or have been on welfare and if their parents were on welfare, too.

20

The Great Recession that is continuing as I write has seriously harmed the mobility of millions of hard-working people thrown out of work or unable to get ahead. But the data simply do not support the idea that the deck is hopelessly stacked against the poor.

Given the facts, it's hardly a surprise to find that huge majorities of Americans believe the U.S. is an opportunity society. In 2005, when Syracuse University researchers asked a cross-section of Americans, “Do you think everyone in American society has an opportunity to succeed, most do, or do only some have this opportunity?” 71.3 percent responded that everyone or most people have an opportunity to succeed.

21

This belief has persisted for many years, probably since the founding of the United States (although there is no data going back that far). The General Social Survey has asked a large sample of Americans since 1973 to answer this question: “Some people say that people get ahead by their own hard work, others say that lucky breaks or help from other people are more important. Which do you think is most important?” For forty years, between 60 and 70 percent of Americans have said “hard work,” while never more than 16 percent have said “lucky breaks.”

22