The Rocks Don't Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah's Flood (14 page)

Read The Rocks Don't Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah's Flood Online

Authors: David R. Montgomery

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Religious Studies, #Geology, #Science, #21st Century, #Religion, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail

Cuvier speculated that extinctions happened during violent geological revolutions, sudden disasters for which he invoked the well-preserved bodies of mammoths as evidence: “In the northern regions it has left the carcases of some large quadrupeds which the ice had arrested, and which are preserved even to the present day with their skin, their hair, and their flesh.”

4

In Cuvier’s view, developed from the great number of fossils he studied, a not quite six-thousand-year-old Earth was simply inadequate to accommodate the diversity of fossil life. Certainly, one great flood was not enough to explain earth history. “Life, therefore, has been often disturbed on this earth by terrible events—calamities which, at their commencement, have perhaps moved and overturned to a great depth the entire outer crust of the globe.”

5

We now know of at least five mass extinctions in the geological past, and biologists say another one is under way as we wipe species off the planet 100 to 1,000 times faster than nature did before we started helping out. Since the evolution of life on land, several events have killed off over half of all animal species. Every school kid learns that dinosaurs died off and mammals began rising 65 million years ago during the great Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event. The less well-known, but far deadlier, Permian-Triassic extinction event 251 million years ago killed off almost all of the animal species on Earth, ending the age of trilobites and setting up the rise of dinosaurs. More recently, the last glaciation of the Quaternary Period (the so-called ice age of the past several million years) saw the demise of megafauna, like mammoths, and ushered in a modern world increasingly dominated by people. When viewed through the geologic record millions of years from now, the modern extinction event we are living through may well look similar to past grand catastrophes that ended ancient worlds.

After Cuvier, the drive to find evidence for Noah’s Flood in the rocks was well and truly dead, although modern creationists would later resurrect the idea. While natural philosophers were long wedded to the idea that fossils confirmed the biblical account of a great flood, once they established the reality of extinctions in the geologic record, it showed that Noah’s Flood could not have deposited all the world’s fossils. They then shifted to looking for the signature of the Flood in the overlying unconsolidated deposits of gravel and boulders. This new view helped natural philosophers and theologians alike accept a pivotal reinterpretation of the Bible, one that made room for a new concept of time—time enough that fossils need not have all died, or lived, at the same time. Thanks to a Scottish farmer, today we know this idea as geologic time.

6

The Test of Time

T

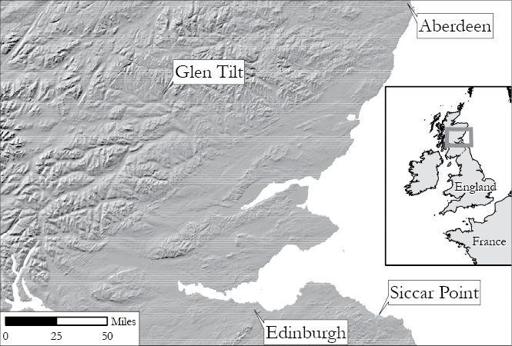

HIRTY MILES EAST OF

Edinburgh lies Siccar Point, a holy site of sorts. The farmer whose fields surround it is said to complain about an endless stream of geologists trampling his turnips. Rock hounds plague this windswept headland because it’s celebrated as the place where Scottish farmer James Hutton discovered geologic time—the place he found the key to unlocking time enough for geological forces to reshape the world. Tucked in along the rocky shore below the turnips are the clear signs of two rounds of mountain building, erosion, and deposition recorded in two sandstones, one gray and the other red.

On a rare sunny Scottish day six of us pulled up at the trailhead and parked just out of view from the farm. We skirted the fields and walked toward the sea cliff, passing by the ruins of a crumbling building amid glowing yellow gorse bushes. I could see striking beds of red sandstone diving down toward the sea to the west. To the east lay planed-off vertical beds of gray sandstone exposed along the shore. Walking out to the headland, we stood above where the two rock formations should meet before starting down a steep grass-covered slope pitching off to the surf below.

Map of Siccar Point, Scotland, showing its position on the coast east of Edinburgh.

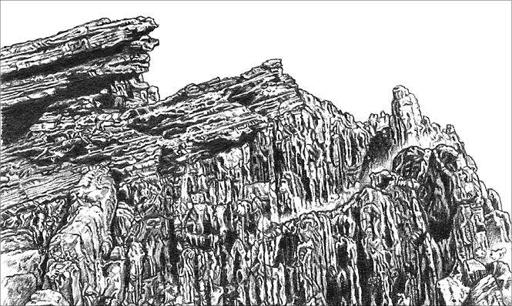

At the bottom lay a jewel of an outcrop. The two rock formations sat there just as textbooks showed. Here, in front of me, were the rocks that helped inspire geology’s core concept of deep time, that the world is billions of years old. Over lunch I read the story in the rocks, laid out plain as day.

The older gray sandstone formed as debris eroded off an ancient upland and settled to the bed of an adjacent sea until the sand eventually lay buried deep enough that heat and pressure turned it into solid rock. Then, something caused the rocks to buckle, lifting them back above sea level and tipping them into their now vertical orientation. Gazing along the shore, I could see how the contact between the two sandstones defined the surface of an ancient valley carved into the gray sandstone. As this new land sank back down beneath the waves of an ancient sea, red sand settled on top, eventually accumulating into enough of a pile to turn it, too, into bona fide rock. After all that, another round of tilting and uplift brought the works back to the surface, where waves peeled the cliff back to expose a low shelf of red sandstone dipping out to sea at a jaunty angle and truncating the underlying vertical beds of gray sandstone.

Hutton’s unconformity at Siccar Point showing the inclined beds of the Silurian Old Red Sandstone truncating vertical beds of Devonian graywacke sandstone

(

by Alan Witschonke based on a photograph by the author

).

When Hutton discovered this outcrop in 1788, it confirmed his suspicion that mountains could be recycled into sand and remade into new rock. I had the advantage of having my colleagues from the University of Edinburgh explain how the gray rock, four-to-eight-inch-thick beds of sandstone separated by thin layers of mudstone, recorded erosion of the mountains that formed the geologic suture from the closing of the ancestral Atlantic Ocean. This collision united England and Scotland 425 million years ago during the Silurian Period, several hundred million years before the days of the dinosaurs. The upper formation, the Old Red Sandstone, formed when the younger Caledonian mountains eroded 345 million years ago in the Devonian Period, with the resulting sand deposited in what is now modern Scotland. The other half of the sandstone derived from erosion of the Caledonian mountains lies across the Atlantic, in New England, as the Catskill Formation in New York and Maine. The present far-flung distribution of the two halves of the red sandstone records the reopening of the Atlantic Ocean well after the life and death of the mountains testified to by the rocks themselves.

Although I’m well versed in thinking about geologic time, I still have a hard time grasping how long it must have taken to raise and erode a mountain range, deposit the resulting sand in the sea, fold up the seabed into another mountain range, and then erode it all back into a new ocean. Siccar Point stands as a natural monument to the unimaginable expanse of time required to account for geologic events.

Of course, in Hutton’s day general consensus placed the world at a mere six thousand years old. The crazy notion of a world old enough to be shaped by the slow accumulation of day-to-day change was beyond radical, it was dangerously pagan.

Nowhere does the Bible say, “the earth is six thousand years old.” This curious belief comes from literally adding up years gleaned from biblical chronology to arrive at how far back the world was created. The second-century historian Julius Africanus was the first Christian to date the Creation by drawing on Egyptian, Greek, and Persian histories. His urgency in dating the dawn of time stemmed from the belief that Christ would return to begin his thousand-year reign before the end of the world precisely six thousand years after it all began. The only way to be sure about when the world would end was to figure out when it started.

Adding up the ages of Adam’s descendants listed in Genesis, Julius convinced himself that 2,261 years passed between the Creation and Noah’s Flood. He then summed up the ages of Noah’s descendants and used extrabiblical sources to determine the dates of key events such as when Moses led the Jews out of Egypt and the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. In this way, Julius determined that Jesus was born precisely 5,500 years after God created the world. Adopting the tradition attributed to the prophet Elijah that the world would only last a thousand years for each day in the week of Creation, Julius predicted that Christ would return to end the world in 500

AD.

His

Chronologia

served as the model for subsequent biblical chronologies, both in approach and motivation.

Centuries later, medieval and Renaissance chronologists generally agreed with Julius that the world would last a thousand years for each day of Creation. They disagreed about when the countdown to the end started, repeatedly pushing the date by which the world would end further into the future as predicted apocalypses came and went without incident. By the end of the seventeenth century, there were more than a hundred biblical chronologies to choose from that set differing dates for the beginning and end of everything.

The most venerated biblical chronology is Bishop Ussher’s influential

Annals of the Old Testament

. Published in 1650, it revealed Sunday, October 23, 4004

BC

, as the date of Creation. Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland, James Ussher was a confidant of Charles I, with an international reputation as a brilliant scholar and one of the largest personal libraries in western Europe. Ussher’s prestige was such that he was buried with full honors in Westminster Abbey.

Ignoring Egyptian and Chinese histories that extended back before his preferred date for the Creation, Ussher concluded that Noah’s Flood occurred 1,656 years after the dawn of time. Noah and company embarked on Sunday, December 7, 2349

BC

, spent a little over a year aboard, and disembarked on December 18 the following year.

How did he establish the year of Creation from the Bible? Like Julius, Ussher tallied up the lifespans of the biblical patriarchs listed in the unbroken male lineage of who begat whom from Adam to King Solomon. To fill in the gap from Solomon to the birth of Jesus, he had to cross-reference biblical events with those of a known age from Babylonian, Persian, or Roman history. Ussher also had to choose which translation of the Bible to use, as the genealogy in the Greek Bible pushes the date of Creation back almost another thousand years. Finally, he corrected for the awkward problem that the first-century Roman-Jewish historian Josephus indicated that Herod died in 4

BC

, and thus that Jesus could not have been born after that since the Bible says that Herod tried to kill the newborn Jesus.

How could Ussher pinpoint the day it all started? He used reason. God rested on the seventh day after the Creation, and the Jewish Sabbath is traditionally Saturday. So, counting backwards six days from Saturday, God started making the world on a Sunday. Assuming that the Creation began near the autumn equinox, Ussher probably used astronomical tables to determine that the equinox occurred on Tuesday, October 25, making Sunday, October 23 the best fit for the day it all began. However he came up with it, in 1701, the Stationers’ Company inserted his 4004

BC

date of Creation into a margin note for a new edition of the King James Bible. From then on, his calculated guess as to the age of the world became gospel for many Christians.