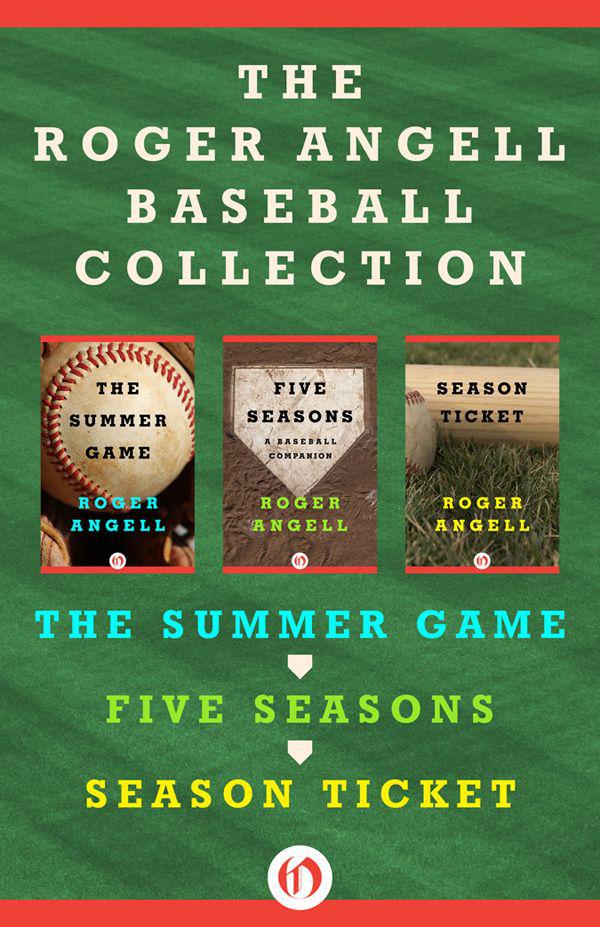

The Roger Angell Baseball Collection

Read The Roger Angell Baseball Collection Online

Authors: Roger Angell

Tags: #Baseball, #Essays & Writings, #Historical, #Nonfiction, #Retail, #Sports & Outdoors

The Summer Game

Five Seasons

Season Ticket

Roger Angell

The Summer Game

The Flowering and Subsequent Deflowering of New England

Days and Nights with the Unbored

Part of a Season: Bay and Back Bay

Season Ticket

Roger Angell

For my father

The Flowering and Subsequent Deflowering of New England

Days and Nights with the Unbored

Part of a Season: Bay and Back Bay

T

HESE PIECES COVER A

span of ten years, but this book is certainly not offered as a comprehensive baseball history of the period. Most of the great winning teams and a good many of the horrendous losers of the decade are here, while the middle ground is often sketchy. I have written about some celebrated players—Sandy Koufax, Bob Gibson, Brooks Robinson and Frank Robinson, Willie Mays—again and again, while slighting equally admirable figures such as Hank Aaron and Mickey Mantle. It is unfair, but this book is the work of a part-time, nonprofessional baseball watcher. In most of these ten seasons, I was rarely able to attend as many as twenty-five games before the beginning of the World Series; I watched, or half-watched, a good many more on television. Enthusiasm and interest took me out to the ballpark; I never went out of a sense of duty or history. I was, in short, a fan. Unafflicted by daily deadlines or the weight of objectivity, I have been free to write about whatever I found in the game that excited or absorbed or dismayed me—and free, it will become evident, to draw large and sometimes quite mistaken conclusions from an emaciated body of evidence. I have added some updating and footnotes in an attempt to cover up the worst mistakes. When I began writing sports pieces for

The New Yorker

, it was clear to me that the doings of big-league baseball—the daily happenings on the field, the managerial strategies, the celebration of heroes, the medical and financial bulletins, the clubhouse gossip—were so enormously reported in the newspapers that I would have to find some other aspect of the game to study. I decided to sit in the stands—for a while, at least—and watch the baseball from there. I wanted to concentrate not just on the events down on the field but on their reception and results; I wanted to pick up the feel of the game as it happened to the people around me. Right from the start, I was terribly lucky, because my first year or two in the seats behind first or third coincided with the birth and grotesque early sufferings of the Mets, which turned out to be the greatest fan story of all.

Then I was lucky in another way. In time, I made my way to the press box and found friends there, and summoned up the nerve to talk to some ballplayers face-to-face, but even with a full set of World Series credentials flapping from my lapel, I was still faking it as a news reporter. Writing at length for a leisurely and most generous weekly magazine, I could sum things up, to be sure, and fill in a few gaps that the newspapermen were too hurried or too cramped for space to explore, but my main job, as I conceived it, was to continue to try to give the feel of things—to explain the baseball as it happened to me, at a distance and in retrospect. And this was the real luck, for how could I have guessed then that baseball, of all team sports anywhere, should turn out to be so complex, so rich and various in structure and aesthetics and emotion, as to convince me, after ten years as a writer and forty years as a fan, that I have not yet come close to its heart?

R.A.

Rustle of Spring

BOX SCORES

T

ODAY THE

TIMES

REPORTED

the arrival of the first pitchers and catchers at the spring training camps, and the morning was abruptly brightened, as if by the delivery of a seed catalogue. The view from my city window still yields only frozen tundras of trash, but now spring is guaranteed and one of my favorite urban flowers, the baseball box score, will burgeon and flourish through the warm, languid, information-packed weeks and months just ahead. I can remember a spring, not too many years ago, when a prolonged New York newspaper strike threatened to extend itself into the baseball season, and my obsessively fannish mind tried to contemplate the desert prospect of a summer without daily box scores. The thought was impossible; it was like trying to think about infinity. Had I been deprived of those tiny lists of sporting personae and accompanying columns of runs batted in, strikeouts, double plays, assists, earned runs, and the like, all served up in neat three-inch packages from Pittsburgh, Milwaukee, Baltimore, Houston, and points east and west, only the most aggressive kind of blind faith would have convinced me that the season had begun at all or that its distant, invisible events had any more reality than the silent collision of molecules. This year, thank heaven, no such crisis of belief impends; summer will be admitted to our breakfast table as usual, and in the space of half a cup of coffee I will be able to discover, say, that Ferguson Jenkins went eight innings in Montreal and won his fourth game of the season while giving up five hits, that Al Kaline was horse-collared by Fritz Peterson at the Stadium, that Tony Oliva hit a double and a single off Mickey Lolich in Detroit, that Juan Marichal was bombed by the Reds in the top of the sixth at Candlestick Park, and that similar disasters and triumphs befell a couple of dozen-odd of the other ballplayers—favorites and knaves—whose fortunes I follow from April to October.

The box score, being modestly arcane, is a matter of intense indifference, if not irritation, to the non-fan. To the baseball-bitten, it is not only informative, pictorial, and gossipy but lovely in aesthetic structure. It represents happenstance and physical flight exactly translated into figures and history. Its totals—batters’ credit vs. pitchers’ debit—balance as exactly as those in an accountant’s ledger. And a box score is more than a capsule archive. It is a precisely etched miniature of the sport itself, for baseball, in spite of its grassy spaciousness and apparent unpredictability, is the most intensely and satisfyingly mathematical of all our outdoor sports. Every player in every game is subjected to a cold and ceaseless accounting; no ball is thrown and no base is gained without an instant responding judgment—ball or strike, hit or error, yea or nay—and an ensuing statistic. This encompassing neatness permits the baseball fan, aided by experience and memory, to extract from a box score the same joy, the same hallucinatory reality, that prickles the scalp of a musician when he glances at a page of his score of

Don Giovanni

and actually hears bassos and sopranos, woodwinds and violins.

The small magic of the box score is cognominal as well as mathematical. Down the years, the rosters of the big-league teams have echoed and twangled with evocative, hilarious, ominous, impossible, and exactly appropriate names. The daily, breathing reality of the ballplayers’ names in box scores accounts in part, it seems to me, for the rarity of convincing baseball fiction. No novelist has yet been able to concoct a baseball hero with as tonic a name as Willie Mays or Duke Snider or Vida Blue. No contemporary novelist would dare a supporting cast of characters with Dickensian names like those that have stuck with me ever since I deciphered my first box scores and began peopling the lively landscape of baseball in my mind—Ossee Schreckengost, Smead Jolley, Slim Sallee, Elon Hogsett, Urban Shocker, Burleigh Grimes, Hazen Shirley Cuyler, Heinie Manush, Cletus Elwood Poffenberger, Virgil Trucks, Enos Slaughter, Luscious Easter, and Eli Grba. And not even a latter-day O. Henry would risk a conte like the true, electrifying history of a pitcher named Pete Jablonowski, who disappeared from the Yankees in 1933 after several seasons of inept relief work with various clubs. Presumably disheartened by seeing the losing pitcher listed as “J’bl’n’s’i” in the box scores of his day, he changed his name to Pete Appleton in the semi-privacy of the minors, and came back to win fourteen games for the Senators in 1936 and to continue in the majors for another decade.