The Rogue: Searching for the Real Sarah Palin (15 page)

The vandalism seems inconsequential compared with Jeremy Morlock’s alleged crimes. The army charged him with murdering the three civilians earlier this year. He is one of a group of five soldiers accused of killing civilians for sport and keeping body parts as souvenirs. He was brought back from Afghanistan in custody on June 3 and is currently confined at an army base in Washington State, awaiting court-martial.

Bristol’s friend April, Jeremy’s sister, is quick to spring to his defense, writing on Facebook: “Please please everyone pray for my brothers release … Love you Jeremy Morlock I am so proud of you no matter how much shit ppl want to talk … You were doing your fucked up job that our country tells you …”

In March 2011, Morlock pleaded guilty to charges that he’d murdered three Afghan civilians. In return for his agreement to testify

against other soldiers in future legal proceedings, he was sentenced to only twenty-four years in prison. He’ll be eligible for parole in 2018.

Obviously, military service doesn’t always solve the problems of a troubled teenager. But it seems to have helped Sarah’s son Track, whose behavior during his high school years paralleled in many ways that of his friend Jeremy Morlock.

Like Morlock, Track was known for his violent temper, often displayed during hockey games. Palin friend Curt Menard told the

New York Times

in 2008 that if you wanted to watch Track play you had to be present at the start of the game. “Track has a temper,” Menard said. “Get there late and he’d already be out.”

The degree to which “hockey mom” Sarah involved herself in Track’s playing career is a matter of debate. The

New York Times

reported in 2008 that she “would drive to rinks at all hours, children in tow. She sometimes ran the scoreboard, let hockey players from other cities sleep on the floor of her home and got involved in the management of her eldest son’s teams.”

I don’t find anyone in Wasilla who confirms this. Instead, I’m told that Track’s biggest problem with regard to hockey was getting to the rink. “Track was always finding his own way,” a team parent tells me. Others recall that it was not Sarah, but state trooper Mike Wooten, when he was married to Sarah’s sister Molly, who would most often drop off and pick up Track. “I almost never saw Sarah at a game,” another parent says. When Sarah did attend, spectators recall that she cheered loudest not for goals, but on those occasions when Track knocked an opposing player down and hit him repeatedly with his stick.

His temper was a problem off the ice, too. “He’s always been out of control,” an old family friend tells me. “He ran over Sarah. He’d shout, ‘Fuck you, don’t tell me what to do!’ and she’d be like, ‘Okay.’ Then she’d run to Todd and say, ‘He’s your son: do something!’ Todd and Track never had a relationship. Zero. I remember being at their

house when Track was sixteen. Whatever it was that had happened, Todd said, ‘No, you’re not going out. You’re grounded. Go to your room.’ And Track said, ‘Fuck you,’ and walked out the door.”

Like Jeremy, Track apparently had problems with alcohol and drugs during his high school years. “At least monthly,” a parent of one of Track’s classmates tells me, “Todd and Sarah would be called to the school because of disciplinary problems with Track.” The

National Enquirer

reported in 2008 that in high school Track was addicted to Oxycontin, quoting a friend of his as saying, “I’ve partied with him for years. I’ve seen him snort cocaine, snort and smoke Oxycontin, drink booze and smoke weed.”

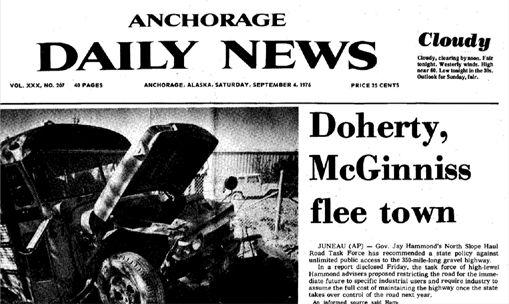

In late November 2005, four Valley teenagers were arrested by state police and charged with vandalizing forty-four school buses: cutting brake lines, deflating tires, breaking mirrors, and unplugging the buses from their engine block heaters to prevent them from starting in cold weather. Because one of the vandals was only sixteen, troopers did not release his name, but word spread immediately in Wasilla that the sixteen-year-old, who was also charged with stealing a bottle of vodka from a liquor store, was Track Palin. An Anchorage radio station and an Anchorage television station identified Track by name in 2008, even before the

National Enquirer

published a story that claimed he was one of the vandals. On September 10, 2008, however, the New York

Daily News

quoted one of those charged, Deryck Harris, as saying that Track did not participate.

Whether or not Track was involved in the school bus vandalism, his problems were apparently so serious that in November of 2006, his senior year at Wasilla High, Sarah and Todd withdrew him from school and sent him to live with friends in Portage, Michigan. He returned to Wasilla in the spring of 2007, but did not graduate from high school. He enlisted in the army on September 11, 2007.

“Track was in pretty big trouble,” a friend of his tells me. “The school bus thing, theft issues, drugs, multiple stuff. Sarah was governor

by then, and Track posed too much risk in terms of PR. So she and Todd sat him down and told him he was going to enlist. They said, ‘You’re gonna do this. You’re gonna do this because you owe us. This is gonna look good for us and you’re gonna do it.’ ”

Sarah made it look even better by arranging the enlistment for September 11, the seventh anniversary of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon. On September 11, 2008, Track was deployed to Iraq, allowing Sarah to proclaim forever after that she was the proud mother of a combat vet. Some might see this as a classic example of taking the lemon that life gives you and using it to make lemonade.

I talk to the state trooper who drove Sarah and Track to the enlistment office in Anchorage on September 11, 2007. “There was quite a bit of emotion in the back seat of that car,” he tells me, “but patriotism was not one of the emotions.”

There is no evidence that Track actually saw combat during his year-long deployment to Iraq, but his presence in a war zone made him a political asset to his mother. Unlike his friend Jeremy Morlock, Track completed his military service without incident.

His army outprocessing order, issued on January 6, 2010, said, “You are released from active duty not by reason of physical disability.” But reports of Track’s drug use persisted even into the summer of 2010.

A family friend says Track, like the other Palin children, has suffered from being made to perform as a member of Sarah’s entourage. “Sarah’s always used those kids as part of this fake image, this illusion she tries to keep up about actually being a decent mother,” the friend tells me. “Those kids never had any parenting, they had to raise each other. And look how it’s turned out.”

How the Palin children are turning out would be of interest only to the Palin family, except for Sarah’s decision to make them an integral part of her public persona. Sarah wraps herself in her children as ostentatiously as she wraps herself in the arms of Jesus and in the

American flag. She uses them shamelessly, from Track in his uniform to Trig in his diapers. But it’s all just part of the show.

DILLINGHAM, WHERE Todd grew up, is more than three hundred miles from Anchorage, has a year-round population of scarcely three thousand, and can be reached only by air or sea. As in so many small, isolated Alaskan towns, drug use and alcohol abuse are epidemic, and when an attractive white woman moves in, she is noticed.

I talked to an attractive white woman who lived in Dillingham in the mid-1990s and who found herself an auxiliary member of “the crew”: a group of young Native men that included Todd’s younger brother, J.D. Because he returned to Dillingham each summer to direct his family’s commercial fishing operation, Todd remained an active member of “the crew.” It did not take long for the attractive white woman to catch his eye.

“Todd hit on me,” she told me in the summer of 2010.

“During summer, the fishing season, Todd was out there, and they’d all flirt with me. I’d probably flirt back. I remember coming out of a restaurant one day and Todd was in his old Ford truck with a boat hooked up to the back, and he was like, ‘Come here.’ I had on these overalls with a bikini top, and he said, ‘I hear lots about you.’ Then he said, ‘Turn around,’ and I said, ‘What?’ and he said, ‘I hear you got a great heart-shaped ass’ and ‘Aren’t you just adorable?’ Todd was hot back in the day, and I remember thinking, ‘Hmmm.’ Then I found out he was married. I was like, ‘Well, I don’t roll that way.’

“J.D. had one of those big Native steams behind his house and he always invited the white girls. A bunch of us would go over. One day Todd made a comment about my nipples being pink. I said, ‘You’ve never seen me naked,’ and he said, ‘Well, maybe there’s a peephole.’ Todd and his friends had been peepin’ on us for months. And he wasn’t some horny teenager; he was a grown and married man.”

IT’S TIME for Nancy to leave. She’s had a pleasant stay on Lake Lucille. She reconnected with old friends from the 1970s and connected with many of the new ones I’ve made since I first returned in November 2008. We visit Tom Kluberton and his companion, Hobbs, at Fireweed Station in Talkeetna, and have dinner at the home of Dewey and Gini King-Taylor. Dewey’s truck has not been vandalized again.

We have coffee with Verne Rupright in his mayor’s office. Catherine Taylor stops by to visit. One night the McCavits, and Shannyn Moore and her partner, Kelly Walters; and Jeanne Devon, who writes The Mudflats, a blog about Alaskan politics, and her husband, Ron, come for dinner.

The lunacy that erupted when I moved in has diminished to the level of nuisance. Some meathead puts up a fake Twitter page with my name on it. My lawyer acts promptly to have it removed. A

Los Angeles Times

blogger repeats the canard that “From his deck, McGinniss … can peer into the bedroom of Palin’s 9-year-old daughter, Piper.” After how many lazy repetitions does a false statement cease to be false? On this one point I agree with Sarah: you can’t trust what you read in the mainstream media.

Nancy has joined me in not peering over the fence.

After a farewell dinner with Tom and Marnie Brennan, Nancy flies out of Anchorage airport on the evening of Saturday, June 12. Her departure is lower key than the one we made jointly in September of 1976.

S

ARAH LEARNED a lesson from her near recall so soon after her election as mayor in 1996: there were limits to the power even of one who believed herself to be on a mission from God. She could get away with firing a popular police chief, but firing the librarian had been a step too far. She could clear the way for more big-box stores to move into Wasilla, but she could not move the museum, which had been deemed a National Historic Landmark. She could keep the bars open until 5:00

AM

, but she couldn’t keep books she disliked out of the library.

On March 27, 1997, Sarah hired a new chief of police: Duwayne “Charlie” Fannon, who had been chief in the southeast Alaska town of Haines for the past eleven years. Before that, Fannon worked for the sheriff’s department in Canyon County, Idaho. He said that as far as he was concerned, the 5:00

AM

closing hour for bars was sacrosanct. In Haines, the bars closed at 5:00

AM

and opened again three hours later. “I have a philosophy that every time there’s a new law or new ordinance we lose a little more of our freedom,” he told the city council. “I don’t think the answer to crime is restricting people’s freedom more and more.” He was confirmed by a 5–0 vote, with Nick Carney abstaining.

Spring arrived. As daylight increases and the cold and snow diminish,

people throughout Alaska tend to mellow. Although Sarah maintained her stranglehold on city hall, passions faded, and the move to recall her died a quiet death. In June the forced resignations of city planner Duane Dvorak and public works director Jack Felton caused little stir.

Also in June, Sarah gave a commencement talk to a group of homeschooled children at the Assembly of God. Although her own children attended Wasilla public schools, she strongly supported both homeschooling and Christian private schools in which students were taught that the creationist theory about the origins of mankind was God-given truth. The Mat-Su College Community Band played music at the event. Afterward, the band’s leader, Phil Munger, spoke to Sarah. Munger, who would later become known for his Progressive Alaska blog, had come to Alaska in 1973 and taught music at the University of Alaska Anchorage. Through his wife’s friendship with John Stein’s wife, Munger was aware that Sarah’s religious views were unorthodox. He asked her about them.

She said she was a “young earth creationist,” convinced that the earth was no more than six thousand years old and that humans and dinosaurs had once walked it together. She knew this was true, she said, because she’d once seen pictures that showed human footprints inside dinosaur tracks.

Sarah also told Munger that civilization had reached the “end-times” and that Jesus would return to earth “during my lifetime.” She said the signs of his imminent return were obvious. “Maybe you can’t see that,” she said, “but I can, and it guides me every day.”