The Sacred Beasts

The Sacred Beasts

by

Bev Jafek

© 2016 Bev Jafek

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced or transmitted in any means,

electronic or mechanical, without permission in

writing from the publisher.

978-1-943837-46-5 paperback

978-1-943837-47-2 epub

978-1-943837-92-2 mobi

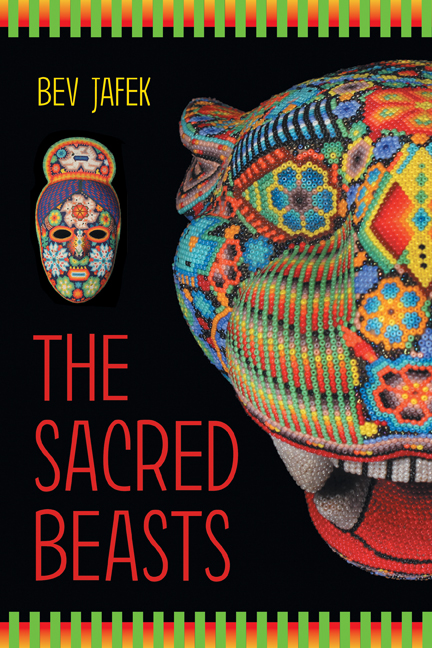

On the cover

Huichol Indian art from the folk art collection of Bev Jafek,

photographed by Elberta Lynn Gaither, 2016.

Cover Design

by

Bink Books

a division of

Bedazzled Ink Publishing, LLC

Fairfield, California

http://www.bedazzledink.com

Ruth, a brilliant zoologist and geologist, has just retired with

her lover, Katia, to her family home in the southern tip of Argentinean

Patagonia. Ruth conceives a unique way of dealing with her grief over Katia’s

sudden suicide with the creation of an outdoor art garden made of cast-off

objects and garbage. Sylvie, a young French artist, is drawn to the art garden

and she and Ruth discover that they are kindred spirits. They travel to Spain’s

Costa Brava and then on to Barcelona—Ruth filtering the world through her

feminist political and zoological/environmental perspective, and Sylvie

capturing the world around her with a vivid, penetrating artist eye. Together

they discover a new concept of liberated women: sacred beasts.

For those who come after us,

when they ask why we did not leave them a world they could live in

and always, for Constance

.

I

THE END

Ruth

II

The Beginning

The Sacred Beasts

III

The Middle

Secrets and Symmetry

I

THE END

Ruth

ONE ALCOHOLICALLY BLACK night, I held my seventh glass of whisky

up to my eye, saw the walls of my living room and its amber lamps jiggling

absurdly in a horrible greenish-brown ooze that inundated the world, drowning

all but me, alone upon my ark. Then I shouted: “You want to know what killed

her?

Mediocrity

! She was meant to be a marvel, a monster, to roar at all

the idiots on this earth!” The sound of my voice shocked me back into sanity.

I was very drunk, alone, shouting the answer to the question that

had haunted me from the moment I read her maddeningly ambiguous note (“Swimming

to Cape Horn. Don’t wait. Love.”) and then found her body dead from drowning,

hypothermia or both on the ocean shore. I began shouting on the second night

after her funeral, the woman who had been my lover for nearly forty years,

Katia, the loved one I always nicknamed, simply, Bear. When the morning

light—bald, blank, insomniac—sank into my marrow, I realized that I had found a

purpose: to create an immense, outdoor sculpture revealing the omnipresence of

mediocrity, that all-powerful aspect of human beings, a work of art suggesting

both suffocation and infinity, made entirely of cast-off metal, plastic and

glass from the city dump. Nothing less would do. That was how my garbage art

garden and my unique form of psychotherapy began.

I had plenty of room for mad projects—several acres of land and an

old, roomy house in Ushuaia, the southern tip of Argentinean Patagonia, closest

city to Cape Horn and the beginning of Antarctica. My house is an international

white elephant, like everything else here, previously owned by an old Welsh

sheep rancher who styled it in the architecture of Wales and the Welsh towns

further north in Chubut Valley: thick bricks, windows sashes and the inevitable

grandfather clock stopped forever in its

tock

. Just call Ushuaia the end

of the world. All the Patagonians do. Old Pat always has plenty to say about

the beginning and end of the world. It’s only the present that so bewilders

her. But in that respect, I’ve always been different. As a retired university

professor, a zoologist, geologist, naturalist, science journalist, and a woman

on top of that, I am a total deviant who is rarely bewildered by the present.

No,

I am absolutely infuriated by it!

“So Little Bear’s shouting to herself at five am now?” The door of

my house, which I rarely lock during our December summer, opened and the

full-cheeked, beguiling Hungarian face of Mariska, my closest friend and

neighbor, looked into my living room and saw the chaotic, disgusting heap that

was myself.

“Don’t call me that ridiculous name again, or I’ll throttle you

against the wall!” I shouted. At least, I was now shouting at someone else.

Some of our friends observed the ridiculous custom of calling us Big and Little

Bear, which revolted me. Katia was unique, another species, as astonishing as

the giant marsupial monsters that lived in ancient Patagonia. More than legend,

they had lumbered over the steppes and deserts during the Neolithic and been

made extinct by early humans. Now enormous, awkward limbs stretched and shook

the ground before my eyes: the elephant-sized mylodon sloth covered with

vividly orange fur, an herbivore so gentle it was brutally penned in caves by

humans until it died for the sole reason that such cruelty met no obstacle. The

equally immense glyptodon armadillo, whose amazing skin was a cross between

armor and fur, reduced to roofing over huts in which fires perpetually burned

and vicious human eyes pooled orange and red demonically before them. Thus the

name of our largest island of archipelagos, Tierra del Fuego, Land of Fire,

courtesy of Magellan who, like all the exploiters, merely feared he might have

found creatures so magically powerful he could not kill them. My species, my

fellows, even then capable of such exorbitant, uncanny greed and destruction

for the sole imperative of fools: that they

could

do it!

How I would love to have shown Bear the sweet, shy monsters,

gentle as doves. What could they have told us of the consequences of being

larger than life? I can nearly see Bear walking beside them in the sunlight,

caressing the sloth’s long orange fur. Could they have saved her?

For I could not. No, I am no smaller, mirror image of Katia. She

was intrinsically

other

: greater and truer than life, like all the women

I have loved. She was a literature professor and a brilliant writer of fiction

and poetry, and we lived in the U.S. for most of our time together. We had only

been in Ushuaia, the home of my childhood, for a year in our mutual retirement.

We left the States in 2004 because we could not bear what the country had

become: a greed and corruption-tainted, dictatorial corporation of the wealthy,

united to steal from the middle and lower classes; a war machine attacking

pathetically weak nations to sell business contracts to millionaires; an

oblivious killer and defiler of the planet; led by the least intelligent and

competent, most immoral government the country had ever known. We felt a

visceral disgust and horror of our nation, but I was the lucky one, citizen of

two lands and, since we were retiring, I brought her to my ancient home. I

thought it would be perfect for her—a wind, snow and light-leavened, open-air

cathedral for worship of nature’s extremity, and the land, flora and fauna that

so perfectly embodied its spiritual value. We had spent months traveling over

the regions I visited many times in my professional life as an expert in the

zoology and geology of Patagonia. I thought she loved it as I did: how fatally

wrong.

My mind turned inevitably to the last moments of her life. This imaginary

scene had been playing in my thoughts, over and over, for two days. Knowing her

so well, I thought I saw the only way she could have ended her life. She was

one who could never stop fighting; she had the perfect hair-trigger response to

enshrined human injustice and blindness. So, she would have picked a place she

could never reach, that ugly black rock, Cape Horn. She entered the churning

sea and began swimming toward it. Then she fought and swam and fought the

water, the cold, the inevitability as the day, the light, fled the sky and

still she went on fighting and drowning in the dark of her own exhaustion,

escaping at last the fierce, demanding purity of her life, becoming the body

that had washed back on the shore where I found it. The tears I myself was

fighting began to fall uncontrollably from her dead eyes, which were closed.

The camera only rewound itself. It would play again.

“I suppose I’ll just pretend I’m not here,” said Mariska, who had

been sitting for some time on the sofa opposite me, greeted by nothing but my

black silence, her still-startling blue eyes, short, whitish-blonde hair and

lovely smile a reminder of normalcy.

“Do that. I’ll help,” I said, my hands with sudden, inexplicable

need covering my face.

“Ruth, you can’t help anyone now,” she said, her voice very

tender.

“I couldn’t help

her

. That’s what matters.”

“No, now

you

matter. A great deal to me,” she said, again

very softly. What a gentle, lovely thing she seemed. I wanted terribly to be

less coarse and brutal but somehow, I could not, though my hands came down to

rest on my lap.

Looking away, I said, “Just tell me this: Do you think there’s a

chance it was anything but suicide? Could it have been . . . any other thing at

all? I thought I knew everything about her.”

Now I could look her in the face, however naked my weakness and

agony were. She held me with the piercing clarity of her blue eyes. “Yes,” she

said at last, “she might actually have believed she could do it. She was like

that. The words

impossible

and

dangerous

were not in her

vocabulary.”

“Oh my god!” I said and slumped over again. “I knew that! I’ve

been thinking it all along and just letting it go. I told her the water could

freeze even in summer down here. I told her the waves reached fifty feet . . .”

Mariska was silent, though I looked at her in great agitation.

“It could surely have been suicide, of course,” she said

reasonably and in a carefully measured tone.

“But . . .”

Again I slumped into my sorrow. “But she could have decided that

such things only applied to others, not to her. Yes, then I knew her. At least

I have that.”

We were silent for a long time, though now we looked freely at one

another. “She was wonderful and terrible,” I said. “I lived with it and loved

it every moment, even when I also hated it.”

“She was all that,” Mariska said. “Will you come to hate Nadia and

me for being, so to speak, merely normal?”

At last, I could muster a ghost of a smile. “No, I intended for us

to be like you. We would grow very old together, and our love would deepen and

darken like amber and somehow we would find that remote island of peace or just

a small, unexpected mirror that reflects a beauty in the world. I only wish I

knew whether she intended to die or to live with abnormal magnificence.”

“They are related.”

“Yes, and tell me this: why do those who love life so intensely

happen to be those who wish for death? Katia often quoted Keats and Shelley.”

The question just hung there between us. Mariska only shrugged and shook her

head as though to say

don’t go there.

Finally I asked, “Did you know how depressed she must have been?”

I was now fascinated with her presence, as though the room now held a Voice of

Truth and not mere fruitless sorrow and rage.

“Yes,” she said, simply.

“I didn’t, dammit! It’s happened so often and this time I didn’t

even know!”

“But you did! You were always trying to convince her she was right

to come here with you.”

“Could you see that?” I whispered in astonishment.

“Oh, yes,” she said. “But has anyone changed Bear’s mind about

anything since they changed her diapers?”

I let out a long, exasperated sigh. “Oh, my god yes. You couldn’t

do anything for her. She just

was

.”

“And that’s what you loved,” she said, even more tenderly.

It was suddenly as though I had swum the course and reached the

black rock of Cape Horn myself. I could breathe again. “There’s something I

must do now,” I said. “I have to get some important things at the garbage

dump.”

“What on earth will you get there?” She looked alarmed.

“You’ll see. I don’t have the energy to explain or justify it, but

it makes sense.” She seemed convinced, more by my sudden calm and determination

than my words.

“I’ve put a beef, cheese and tomato casserole and a fruit salad in

the kitchen,” she said quickly.

“Ah, food,” I said, apathetic. “Not yet for that.”

“It’s been two days.”

“Then maybe I’ll eat. Possibly. Whatever. I can do it when I’m

back from the dump. But I must go right now. I am . . . inspired or . . . just

certain. There’s something I can do and ach, it’s better than sitting here, drinking

and shouting.”

Now there was a spark of recognition in her eyes. “Yes, do it

whatever it is,” then with a doubt, “but you really must do it at the garbage

dump?”

“Absolutely. Something about beginnings and endings. Old Pat can

tell you.”

“Old Pat? You mean the natives?”

“Yes, aren’t

we

the natives, too? So it should be perfectly

clear.” I smiled angelically and walked out the door.

Outside, I fired up my pick-up truck, a foul old dirigible that

had once clambered over all Patagonia, hauling my infrared cameras, portable

chem labs and the other scientific sensors and equipment I had used in my

studies of animals and landforms. It was a decent old barreling iron horse,

like me. I had always felt an affinity for it. We both bore our burdens well

without a trace of beauty, the sign of final, bitter maturity. The truck had

the tires of a jeep, and Bear and I had driven and camped throughout Patagonia

and the States with it.

As I drove, I looked at the ocean, hoping that my mental film reel

of Bear’s death would not begin running again. Instead, I saw beds of giant

kelp that grew in vast, burgundy tangles for miles along the coastline. No, she

didn’t enter the sea here. The wet, shining tubular arms of the kelp would have

held her back with a force like love.

Early morning in Ushuaia is a still, near-perfect calm that

extends well into the sea. The southern Darwinian range of the Andes encircles

the city, giving it some of their pristine, cold mountain air. The only sound

is that of the eternal wind, invisible spirit of the Andes, the force called

Mara

,

Broom of God that has sculpted many of Patagonia’s strangest landforms.

I do not hate the wind, as many do, for I have heard it whistle,

purr, moan, shriek, cackle, wail, and then sing like a drunken sailor on the

steppes. On our camp-outs, we saw the wind whirl through deserts not of sand or

gravel but a colorless white dust streaming off ancient saltpans and grey-green

scrub with sharp thorns and bitter odors. At night, when we disappeared into

our sleeping bags, only our eyes looking out at the moon glimmering over

fossilized shells of oysters, for the steppe was once an ancient seabed, it was

then I learned the tonalities of the wind’s voice: whirring through the thorns;

whistling through the dead grass; then in full throat shaking the tiny, dry

possessed bushes, making dervishes of them, in song! Rude, rough, barbaric song

came from those wildly heaving bushes! Bear loved it, too, and pronounced them

the crazed, curly heads of pagan warriors, shouting and singing at once in a

battle without end.