The Sahara (30 page)

Authors: Eamonn Gearon

Tags: #Travel, #Sahara, #Desert, #North Africa, #Colonialism, #Art, #Culture, #Literature, #History, #Tunisia, #Berber, #Tuareg

Typical of this realism is

The Snake Charmer

(1889). Painted in Laghouat, it shows an elderly, bearded snake charmer at the centre of the picture with a benevolent smile on his face and a snake on top of his head, with another held between his right thumb and forefinger. In the expressions of the semi-circle of spectators the viewer sees an array of emotions, including awe, fear, concern and pleasure. The faces of the men and boys who have gathered for the show are so beautifully observed that although it is taking place in a public arena, Dinet creates a sense of the intimacy of a private encounter.

Like Dinet, Fromentin and Guillaumet also drew inspiration from daily life in Saharan oases. The slice of life in Fromentin’s

A Street in El Aghouat

(1859) is clearly based on first-hand experience. A common enough scene, the picture shows half a dozen men doing their best to rest while hiding from the heat, recumbent in the midday shade that barely covers a portion of the village street, dividing the public space into two distinct spheres of light and dark. Another ordinary scene captured by Guillaumet is that of a group of women drawing water in

The Seguia, Biskra

(1884), an image which has essentially remained unchanged since the oasis was settled in Roman times. Other scenes of daily life inspired Guillaumet to paint

Saharan Dwelling, Biskra District, Algeria

(1882) and

Laghouat, Algeria

(1879), studies of such mundane activity as the preparation of food. In

Evening Prayer in the Sahara

(1863) by Guillaumet, the figures of the group of worshippers in various stages of prostration during sunset prayers bring the divine into the Sahara, as behind them the smoke rises from the campfires.

The American artist Frederick Arthur Bridgman (1847-1928), sometime student of French painter and sculptor Jean-Leon Gerome, spent a number of winters in Egypt and Algeria during the 1880s, both on the coast and in the Sahara. A native of Alabama, Bridgman had seen slave markets first-hand in his home state before the American Civil War. As a result, he became a committed anti-colonialist, sympathies he transfers to the downtrodden North African locals, for instance in the affectionately executed

Interior of a Biskra Café, Algiers

(1884). Although eventually settling in France, he continued to paint Algerian scenes which became, perhaps because of the distance and a faulty memory, increasingly saccharine, taking on the look of syrupy illustrations for a children’s edition of the

Arabian Nights.

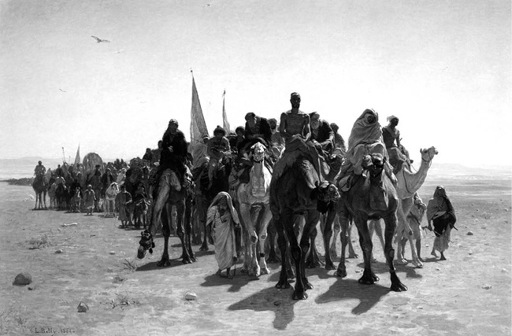

In stark contrast to Bridgman’s chocolate-box period, the dramatic almost featureless landscapes by Guillaumet and others proved inspirational to Leon Belly, who created one of the most famous desert scenes of the nineteenth century in

Pilgrims Going to Mecca

. Although almost as much a part of the landscape as the stones and sand itself, until this time camels were not the first choice of artists painting Saharan scenes. This changed, however, when Belly’s painting was unveiled in 1861. It is not hard to see why this epic work, which measures almost eight feet by five, has become a classic of its genre.

Unlike romanticized images, Belly’s painting offers an altogether more realistic, indeed sympathetic, portrayal of pilgrims as individuals, rather than a group of stereotypes. The elderly and the exhausted feature with the heat and blinding light - all elements given equal weight in the tableau. The believers are marching in the heat with the sun at their back forcing the picture’s detail into the dark places. The placing of the pilgrims too, looming front and centre, lends grandeur to the group of otherwise ordinary people. The seemingly infinite column of pilgrims forms a pyramid that reaches the top of the picture and back away across the endless plain, again devoid of soft colours or shade.

Léon Belly, Pilgrims Going to Mecca, 1861

Where Belly led, many followed. At a brush-stroke, the camel caravan became not only acceptable as a subject, but

de rigueur,

virtually every artist who portrayed camels after Belly was in his shadow. Ludwig Hans Fischer’s (1848-1915) treatment of the subject is beautifully shown in a pair of paintings,

An Arab Caravan

and

An Arab Caravan at Dusk

(1903). The first of these in particular creates a sense of heat, but both works impart that extreme stillness that is only found in the desert, where even the camel’s padded feet seem to have been designed to maintain this silence.

In contrast to these tranquil scenes, Fischer also produced an extremely animated work in

The Simoom

(1878), a study of a sandstorm. The presence of an ancient statue, suggesting the possibility of nearby water, is the only thing that prevents this from being an image of pure terror. The picture of men battling through a storm, accompanied by their distressed sheep and a lone donkey, is uncomfortably realistic. Adverse weather is also the subject of Fromentin’s

Windstorm on the Esparto Plains

(1864), which features, for Fromentin, an uncharacteristically dark sky, the greys adding to the storm’s menace. Apart from the storm, the picture’s focus is the discomfort of a group of horsemen, caught on the plains with no shelter in sight, as their burnouses billow about their heads.

After camels, the animal that features most prominently in Saharan art is the horse. In 1851 the French general Melchior Dumas published

Horses in the Sahara

, aided by the exiled Abd al-Qadir. The book is a study of animal husbandry and the uses and treatment of horses in the West versus North Africa. Fromentin and others seized upon the book as invaluable source material.

In

Moroccan Horsemen in Military Action

(1832) by Delacroix, the majesty of the horses is tempered by the fear in their eyes as they take their mounts into battle. Horses also feature prominently in the work of Gerome (1824-1904). In setting the standard for documentary realism commonplace by the second half of the nineteenth century - Gerome was disparaged by many who came after him as cold and static, especially by the Impressionists, who favoured a freer, more interpretive approach in their work. In

Arabs Crossing the Desert

(c. 1870), Gerome places a noble looking group of horses and riders directly in front of the viewer, with camels relegated to the background as little more than set dressing. The view he offers is that while camels may be the more useful animals for a desert crossing, the horse is endowed with greater nobility. The all-male setting, devoid of any hint of domesticity, likewise promotes masculinity in the imagined nobility of his desert-dwelling Arabs. Adding to the romance of what might otherwise be considered a realistic scene is the riders’ garb, the rich, dust-free clothes shining out in contrast to the dun-coloured landscape surrounding them.

The portrayal of women in the general field of Sahara-inspired Orientalist art usually involves the convention of shrouded or naked forms. In the paintings of the nineteenth century, women are rarely depicted in harems - more commonly associated with palaces found in the major urban centres such as Constantinople or Cairo, and thus absent from the Sahara proper. The questionable taste of many fantasy images of bondage and eroticism in many of these scenes no doubt contributed to the wholesale devaluation of Orientalist art as a genre.

For examples of a more restrained, even respectful portrayal of women in the region, one could look to

Morning Walk

by the Italian Rubens Santoro, or

Women in Biskra Weaving a Burnoose

(1880) and

Portrait of a Kabylie Woman

(1875), by Bridgman. None of these shows the female subjects in a demeaning light; instead they are almost shying away from the more salacious harem portraits of other so-called Orientalists.

Portrait of a Kabylie Woman

in particular portrays a subject whose strength and single-mindedness are clear in her face, in contrast to the naked, pale-skinned women examined in a slave market or waiting in a harem.

In this regard,

The Almeh’s Admirers

(1882) by Leopold Carl Muller and Gerome’s

The Dance of the Almeh

(1866) are far more sexually straightforward images, both pictures featuring the

Almeh

dancing for an all-male audience. Literally a learned woman, in reality an

Almeh

was a dancer who would often also work as a prostitute. In Muller’s piece, the dancer, who is staring directly at the viewer, seems unaware of her audience who are focusing on one or another of the woman’s curves, laughing or, in the case of the musicians, concentrating on their work.

If so-called Orientalist art was a nineteenth-century phenomenon, it is not always obvious what legacy the artists of the next century who travelled in the footsteps of Delacroix

et a

l inherited. Most of these moved away from the studio-executed or studio-finished work of their predecessors, now seeking more immediacy and spontaneity in their work. This change of direction meant that Orientalist art was actually replaced by a looser informal brotherhood of painters, sometimes referred to as colonialist artists, who travelled and lived in the region both before the Second World War and after independence.

By and large, the Impressionists found little inspiration in the Sahara. Claude Monet (1840-1926), for example, did his military service in Algeria, and although he wrote favourably of his time there this did not translate into any major works inspired by the country. Although Renoir (1841-1919) is sometimes said to be the most Orientalist of the Impressionists, making several trips to Algeria in 1881 and 1882, he likewise did not obviously take any Saharan subject matter away with him, concentrating instead on the cities and gardens of the Mediterranean coast. In this region, Renoir, as Matisse after him, delighted in the textures and colours offered by the vegetation of North Africa.

Renoir and Matisse were both happy to acknowledge the debt they owed to Delacroix, although as Matisse once said of himself “I am much too anti-picturesque to get much out of travelling.” Even so, he did travel to Algeria in 1906, going to the oasis of Biskra, and made two lengthier Moroccan visits in 1912 and 1913 although these were limited to Tangier. His interest was less specifically in landscapes than figures, and his

Odalisque

series of paintings are much more like the studio-based Ottoman fare of the nineteenth-century artists than any of his contemporaries.

The work of the German Symbolist Paul Klee (1879-1940) may not at first speak of the Sahara, but it was in Tunisia in 1914 that he enjoyed a breakthrough in his work. Klee claimed to have discovered colour and abstraction in Tunis and Hammamet, after which he travelled to Kairouan and the desert beyond, which he described as the high point of his Tunisian tour. As he wrote during his trip, “Here is the meaning of this most opportune moment: colour and I are one. I am a painter.” In 1928, during his first trip to Egypt, he described the quality of light and colours there in similar terms. Whether or not one cares to describe Klee as an Orientalist artist, it is undeniable that his work was informed by what he found in North Africa. As his diaries make clear, it was there that he learnt about light in the desert and simplicity from local architectural forms that informed the rest of his life’s work.

Anyone who attempts to lump together the traveller-artists of the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries as cultural imperialists misses the point by a considerable margin. Wrong as it is to assume the homogeneity of those who live in the Sahara, so is it misguided to think of the artists who travelled there as consistent in intention and outlook. Often criticized as little more than ignorant, paint-carrying tourists, it is true that some came in search of the seamy. Yet for every traveller who hoped to confirm some prejudiced view of the region as a land of harem-dwelling sex slaves, implacable pederasts and unholy despots, one can point to any number of artists whose interests lay in more innocent pursuits.

What is true is that numerous artists, including Delacroix, Fromentin, Renoir, Matisse and Klee, found their work altered by the time they spent in the Sahara. Each artist found his work developed in practical ways, opening up new sights and new directions. This was often the result of exposure to the Saharan sun, and the effect this light had on the colours of the region. More than anything else, it was the light which these artists took away with them from the desert - a brilliance they could not hope to find under European skies.