The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards (21 page)

Read The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards Online

Authors: William J Broad

Tags: #Yoga, #Life Sciences, #Health & Fitness, #Science, #General

Black said he worked hard at trying to recognize signs of danger and knowing when a student “shouldn’t do something—the Shoulder Stand, the Headstand, or putting any weight on the cervical vertebrae.”

I asked if he ever modified poses to make them safer.

“Constantly,” he answered. Referring to our just-completed class, Black noted how we had done a standing pose where we had put our arms behind our backs, clenched our hands together, and stretched our arms up. “I could see people’s faces crunching, so I said, ‘Bend your elbows.

’

” It was, he said, a safety valve.

“To come to New York and do a class with people who have many problems, and say, ‘Okay, we’re going to do this sequence of poses today’—it just doesn’t work.” Instead, he said, all classes had to be tailored to the range of particular student abilities on that particular day.

Weber noted that she had been studying with Black for a decade and had never experienced the same class twice.

Black said his guiding principle in teaching yoga was to downplay the asanas and put the emphasis on awareness. “It’s harder to teach,” he said. “But the risk of not teaching it is very great. If you just teach people to do an asana without taking them into deeper states of realization, their asanas are always going to be a struggle.”

The superstars of yoga were so addicted to celebrity that they often overlooked the message of awareness and paying close attention to their bodies and anatomical limits, Black said. He told of famous teachers coming to him for

healing bodywork after suffering major traumas. “And when I say, ‘Don’t do yoga,’ they look at me like I’m crazy. And I know if they continue, they wouldn’t be able to take it.”

He said yoga celebrities seemed to have a predisposition to engage in not only personal denial but social evasion. “A yogi I know was going to be interviewed by

Rolling Stone

and said, ‘I don’t want to talk about injuries.

’

”

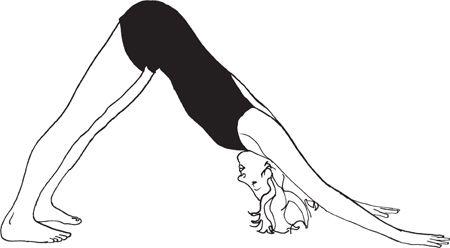

I asked about the worst injuries he had seen, and Black rattled off a long list. He told of big-name yoga teachers doing the Downward Facing Dog so strenuously that they tore Achilles tendons. “It’s ego,” he said. “The whole point of yoga is to get rid of ego.” He said he had seen some “pretty gruesome hips. One of the biggest teachers in America had zero movement in her hip joint. The socket had become so degenerated that she had to have a hip replacement.”

Downward Facing Dog,

Adho Mukha Svanasana

I asked if she still taught. “Oh, yeah. And there are other yoga teachers that have such bad backs that they have to lie down to teach. I’d be so embarrassed.”

Black said that he had never injured himself or, as far as he knew, been responsible for harming any of his students in thirty-seven years of teaching. “People feel sensations, sure, and find limitations. But it’s done with mindfulness, not just because they’re pushing themselves. Today, many schools of yoga are just about pushing people.”

He told of his students reporting back to him on the aggressive tactics of other instructors. “

You can’t believe what’s going on—teachers jumping on people, pushing and pulling and saying, ‘You should be able to do this by now.’ It has to do with their egos.”

Black also chided students who practiced yoga for the excitements of status and cachet. “They take a class to show off their Missoni T-shirt or their leotards,” he said, scowling. I asked his opinion of

Yoga Journal,

which over the decades had gone from a geeky nonprofit published by the California Yoga Teachers Association to a glossy magazine filled with ads for sexy clothing, travel adventures, and miracle weight-loss drugs. He declined comment.

While many gurus and yogis over the decades had remained silent on the threat of injury, or had denied its existence, or had grudgingly made limited concessions of danger, Black insisted that the threat was now indigenous to the discipline and just waiting to strike. He argued that a number of factors had come together in modern times to heighten the risk.

The biggest was the changing nature of students. The poor Indians of yoga’s past normally squatted and sat cross-legged, the poses thus being in some respects an outgrowth of their daily lives. Now yoga had become a Western fad, swelling its unskilled ranks. Urbanites who sat in chairs all day now wanted to be weekend warriors despite their inflexibility and physical problems. Amateurish teachers ruled like drill sergeants and pushed cookie-cutter agendas. Such factors became all the more deadly, Black argued, with the distractions of modern vanity, which kept students and teachers from focusing on the importance of the here and the now, from listening to their bodies and understanding when they were about to cross the line from a wholesome stretch to excruciating harm.

The result was an epidemic.

“There has to be a degree of seriousness and dedication,” he said. “Otherwise, you’re going to get hurt.”

The first scientific light on the topic of yoga injury fell decades ago. The reports appeared in some of the world’s most respected journals—including

Neurology,

the

British Medical Journal,

and

The

Journal of the American Medical Association.

The high-level debut signaled that the medical establishment saw the findings as important information that practicing doctors needed to know if they were going to help patients. The reports began to

emerge in the late 1960s, soon after the West had become newly interested in yoga.

A number of early findings centered on nerve damage. The problems ranged from the relatively mild to permanent disabilities that left students unable to walk without aid. For instance, a male college student had done yoga for more than a year when he intensified his practice by sitting upright for long periods on his heels in a kneeling position known as Vajrasana. In Sankrit,

vajra

means “thunderbolt.” The position, also called the kneeling pose, is sometimes recommended for meditation. The young man did the pose for hours a day, usually while chanting for world peace. Soon he was experiencing difficulty walking, running, and climbing stairs.

Thunderbolt,

Vajrasana

In Manhattan, an examination showed that both of his feet drooped because of a lack of leg control, and doctors traced the problem to an unresponsive nerve. It was a peripheral branch of the sciatic, the longest nerve of the body, which runs from the lower spine, through the buttocks, and down the legs. The damaged branch ran below the knee, normally providing the lower leg, foot, and toes with sensation and movement. Apparently, the young man’s kneeling in Vajrasana had clamped his knees tight enough and long enough to cut the flow of blood to the lower leg,

depriving the nerve of oxygen. The result was nerve deadening.

It was suggested that the young man simply give up the pose. Reluctantly he did so, opting instead to do his chanting while standing. He improved rapidly, and a checkup two months after the initial visit showed no lingering problems. In describing the case, the attending physician called the condition “yoga foot drop.” The name stuck. In time, a number of similar cases emerged.

One of the worst featured a woman of forty-two. She fell asleep in Paschimottanasana—the Seated Forward Bend, its Sanskrit name meaning “stretch of the West.” Upon awaking, she found her legs numb and weak. A medical team at the University of Washington, writing in

The Neurologist,

told of finding injuries to both her sciatic nerves that had crippled her legs. The scientists reported that the woman regained “some sensation” after three months of therapy but still displayed persistent foot drop.

Seated Forward Bend,

Paschimottanasana

A half year after the mishap, the woman was still unable to walk without assistance. Her doctors said evidence of permanent nerve damage left them doubtful that she would ever recover full use of her legs.

If the first reported cases were relatively minor, a second wave soon emerged in which the consequences were little short of devastating. The reason was that the damage centered on the brain itself—not some peripheral organ or physiological subsystem. The news got worse. The blows to the body’s most important organ arose not from stretching too much or holding postures too long but from the skilled practice of poses that practitioners did routinely and tended to see as completely safe.

The situation was so ominous that a leading British physician issued a public alert. In

the conservative world of medicine, it is a rare day when abstract theorization comes ahead of clinical reports. Usually it is the other way around—first observation, then efforts at explanation and generalization. But the physician had the requisite stature to issue a sharp warning even before his peers had published any reports that described particular cases.

At the time, in 1972, W. Ritchie Russell was an elder statesman of British medicine. The string of acronyms after his name bespoke his status: M.D. (Medical Doctor), C.B.E. (Commander of the British Empire), F.R.C.P. (Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians), and D.Sc. (Doctor of Science). A neurophysiologist, he had distinguished himself in a long career at Oxford University that showed, among other things, that brain injuries could arise not only from direct impacts to the head but from quick movements of the neck as well, including whiplash. He published his pioneering research in the early 1940s as war swept Europe and neck injuries grew rapidly in number.

His new warning centered on how some yoga postures threatened to reduce the blood flow to the brain and cause the cerebral disasters known as strokes. The second most important cause of death in the Western world, right after heart disease, strokes often strike older people whose arteries get clogged with fatty deposits. The risk of dying from them rises with age. In addition, Russell worried about a fairly rare type of stroke that tended to strike relatively young, healthy people.

The word “stroke” is a euphemism for a range of destructive nastiness that develops when the regular flow of blood to the human brain gets interrupted. In many cases, the symptoms arise on just one side of the body because the brain’s functional areas mirror the body’s bilateral symmetry. Most strokes start as simple blockages. The flow of blood through an artery gets reduced or blocked entirely by deposits of fat, clots of coagulated blood, or the swollen linings of torn or damaged vessels, robbing the brain of oxygen. By definition, strokes traumatize and kill brain cells, which are known as neurons. A renewed flow of blood can sometimes mend beleaguered cells. And over time, nearby neurons can sometimes replace the function of dead cells. But damage can also be permanent. Stroke victims thus experience disabilities that range from passing weakness to lasting neurologic damage to death if the destruction involves vital

brain centers. (Fast treatment can limit the damage, which is why health professionals urge speedy evaluations of suspected stroke victims, preferably within sixty minutes.) The symptoms of stroke vary widely because of the brain’s highly specialized anatomy. For instance, conscious thought and intelligence arise in the outer layers of the brain, so strokes in those areas can affect speech and critical thinking.