The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards (8 page)

Read The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards Online

Authors: William J Broad

Tags: #Yoga, #Life Sciences, #Health & Fitness, #Science, #General

His big opportunity arrived when a wealthy industrialist hired Gune for a teaching job at one of his pro-independence schools. Gune rose quickly. By 1920, his patron put him in charge of a small college. But Gune found himself out on the street in 1923 when authorities shut down the college for agitating against British rule.

His benefactor again came to the rescue. This time he gave Gune a large donation that let the jobless educator take the biggest step of his life and found the scientific ashram.

In his research, Gune made up for lost time, publishing a flurry of findings in

Yoga Mimansa.

Its language was English, signaling its wide target audience. He presented two studies in 1924, six in 1925, four in 1926, seven in 1927, and so on. Early on, he performed more than a dozen X-ray studies of yogis in various states of contortion. This surge was unique for the day.

“We cannot make even a single statement,” Gune boasted, “without having scientific evidence to support it.” That, of course, was a fairy tale. But it showed the depth of his enthusiasm.

The yoga taught at the ashram had been carefully repackaged. No untidiness was tolerated, nor ashes nor unkempt hair. Everything was squeaky clean—like science itself. Yoga’s unsavory aspects had suddenly vanished.

Throughout his career, Gune maintained a virtual taboo on the word “Tantra”—the parent of Hatha that Hindu nationalists had come to abhor. Students heard nothing about thrills similar to “the bliss experienced in sexual orgasm,” as White had put it. They got no tips about extended lovemaking, as the

Hatha Yoga Pradipika

had instructed. All that was off the public agenda. The reformulated program had to do with giving yoga a bright new face that radiated with science and hygiene, health and fitness.

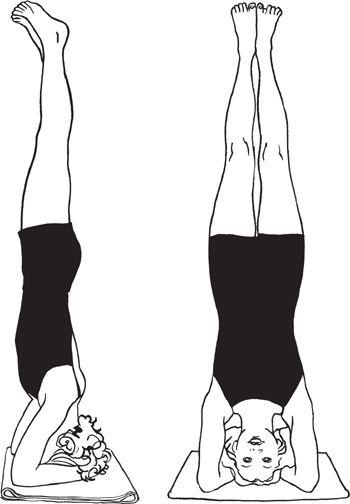

Gune’s investigations could be quite technical, despite his lack of formal scientific education. An early one centered on high blood pressure. The question was whether the risks of challenging poses outweighed the benefits. To study the problem, Gune had eleven students do the Headstand and the Shoulder Stand, two of yoga’s most demanding poses.

Headstand,

Sirsasana

Inversions, by definition, can unnerve. Quite

suddenly, new students find their worlds upended and their hearts racing. Once beginners have achieved a measure of skill and confidence, however, they tend to find the poses strangely relaxing or, at other times, exhilarating. The conventional wisdom is that inversions reverse the effects of gravity, invigorate the circulation, and flood the vital organs and brain with nourishment, bringing about a rush of rejuvenation.

Gune and his aides found that the poses, though demanding, tended to be gentle on the heart. The traditional measure of blood pressure is how high it raises a column of mercury, and the usual daytime reading for a resting adult is around 120 millimeters. For the Headstand, Gune found that the average readings started at 125 millimeters, rose to 140 millimeters at the end of two minutes, and settled back down to 130 millimeters by the end of four minutes. That modest rise, he argued, compared favorably to how

the hundred-yard dash, for instance, resulted in blood pressure soaring as high as 210 millimeters.

He wrote that the inversions still achieved the goal of “getting a richer blood supply” to undernourished parts of the body despite the “comparatively low rise” in pressure and the modest physical effort. Not that muscles were neglected. “We have ample evidence,” Gune boasted, that the poses represent “an unrivalled set of exercises even for the towers of strength!”

Throughout his career, Gune showed a fondness for the zing of exaggeration. He was, after all, part showman. With the implied authority of his white lab coat, Gune worked hard to advance not only the substance of science but its style. He wanted to cultivate the idea that science had endorsed yoga—to demonstrate its approval and borrow some of its repute and progressive energy as a means of giving the discipline a new air of respectability. He desperately wanted yoga to project a new image.

But Gune also exhibited real depth. Surprisingly, given his raw political objectives and lack of formal scientific training, he repeatedly displayed a love of rigor. He even managed to disprove one of yoga’s central tenets.

Yogis of his day (and ours) were happy to appear scientific by declaring that deep breathing had hidden powers of rejuvenation because it flooded the lungs and bloodstream with oxygen, refreshing body, mind, and spirit. They taught that students who did intense yoga breathing could feel the body tingle and vibrate with waves of healthful oxygen.

Not so, Gune countered after doing a pioneering set of measurements. Instead, he found that fast breathing did little to change the amount of oxygen that the bloodstream would absorb and determined that such vigorous efforts actually made their biggest impact by blowing off clouds of carbon dioxide.

“The idea that an individual absorbs larger quantities of oxygen during Pranayama is a myth,” he wrote, referring to the yogic name for breathing exercises. Gune’s finding might have been counterintuitive and contrary to the wisdom of the day. But it was stubbornly honest—and, as it turns out, scientifically correct.

A smart fund-raiser, Gune sent free copies of

Yoga Mimansa

to the maharajahs of India. These rich men presided over a patchwork of princely states exempt from direct British rule. Many patronized the indigenous arts and culture

as part of the Hindu revival, and some had a lively interest in yoga.

His influence rose so fast and to such a degree that he quickly became a hero of the nationalist intelligentsia. By 1927—just three years after the ashram’s founding—the former unemployed schoolteacher was advising Gandhi, arguably the most famous Indian since the Buddha and the most visible leader of India’s fight for independence.

The issue was the pandit’s health. Gandhi had had serious bouts of illness and fatigue often aggravated by his long fasts, as well as a fascination with natural cures and a disdain for Western medicine. He complained of high blood pressure. Gune recommended the calming effect of the Shoulder Stand. “In your case,” he wrote in one letter, the pose “should certainly help.” Gune noted that his own practice of the inversion left his blood pressure at a relaxed 120 millimeters of mercury.

Gune often promoted specific poses for particular ills and health benefits, pioneering an approach that many yogis would adopt over the decades. And he promulgated other innovations. Soon after founding the ashram, Gune, drawing on the inspiration of a martial arts mentor, established a policy of teaching yoga in classes of mass instruction. The lessons, moreover, were free.

Another novelty centered on women. At first, the ashram took in only male students. But that policy soon changed. By 1926, Gune was calling his reformulated yoga “peculiarly fitted for the females.” His observation was farsighted, given the traditional male chauvinism of Hindu society and yoga’s eventual popularity with women.

To say that Gune was pivotal understates the case. Even so, he remains virtually unknown in the West except among scholars. Joseph S. Alter, a medical anthropologist at the University of Pittsburgh and author of

Yoga in Modern India

, argues that he “probably had a more profound impact on the practice of modern yoga than anyone else.”

Of Gune’s many admirers, one of the most politically astute was the Wodeyar clan of Mysore, a city and state of southern India rich in silk and incense, coffee and sandalwood. The benevolent rajahs ruled over a realm about the size of Scotland, their ornate palace dominating the capital. Mysore was the most progressive of India’s princely states, and historians say the ruling family played a skillful role in the politics of Hindu nationalism, including the

promotion of yoga as a way to build an Indian national identity.

Like Gune at his ashram, the Mysore palace sponsored a version of the ancient discipline that was far removed from the world of Tantra and eroticism. It was quite unmystical. For decades, members of the family had practiced an eclectic style that drew on Indian martial arts and wrestling as well as Western gymnastics and physical fitness techniques, including those of the British. It aimed at promoting martial culture, hardening the body, and producing feelings of pleasurable fitness.

In 1933—a decade after Gune had turned to the scientific study of yoga—the palace hired a teacher to run its yoga hall. This short man of quick temper and considerable erudition, Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, had spent his early life learning Sanskrit, Indian medicine, and other classical disciplines as part of the Hindu revival. He now developed a style that drew on the palace’s gymnastic ethos.

Krishnamacharya refined postures, sequenced them with logical rigor, and combined them with deep breathing to create a fluid experience.

None of this would matter very much except that Krishnamacharya (1888–1989) produced a number of gifted students who eventually made him history’s most influential figure in Hatha’s modern rise. His passion and ideas about pose development led to the emergence of the Sun Salutation and eventually other flowing poses and styles, including Ashtanga and Vinyasa, Power and Viniyoga.

The Mysore palace sent Krishnamacharya on tours around India to publicize yoga, with the participants openly referring to the trips as “propaganda work.” In 1934, the maharajah asked Krishnamacharya to visit Gune’s famous ashram up north and study its methods. Krishnamacharya did so, traveling by train.

The following year, the palace guru adopted the theme of therapeutic benefits in his own book,

Yoga Makaranda

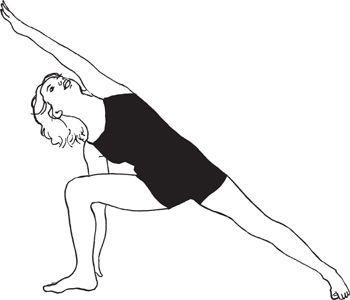

(Honey of Yoga), which the maharajah published. This sequel to Gune’s therapeutic efforts was even more tenacious. For instance, it hailed the benefits of Utthita Parsvakonasana—a triangular pose known as the Extended Side Angle. The student bends one leg and keeps the other ramrod straight, lifting one arm over the head and bringing the other down to the floor. As a result, “pains in the abdomen, urinary infections, fevers and other diseases will be cured,” the book declared with no hint of qualification, or proof.

Extended Side Angle,

Utthita Parsvakonasana

Krishnamacharya may have been stubborn,

gruff, and domineering but he trained a student who proved to be particularly important to the spread of Hatha yoga—his brother-in-law, B. K. S. Iyengar (1918– ). The young man had been sickly all his life, and at first the yoga sessions in Mysore went poorly. Krishnamacharya soon lost interest in his new student. But Iyengar kept at it and eventually became healthy. Increasingly, like his guru, he looked to yoga for its restorative powers. He began touring India with Krishnamacharya and displaying his newfound skills, effortlessly tying his body in knots.

Iyengar, a young man of eighteen, at this point began to draw on the insights of medicine. It helped him ground his approach more deeply in the modern view of the body. His strategy was similar to what Gune and his colleagues had done—but in miniature.

The immersion began in 1936 when a surgeon by the name of V. B. Gokhale watched in astonishment as Iyengar gave a yoga demonstration and afterward helped facilitate Iyengar’s relocation to the large city of Pune, which became Iyengar’s home for the rest of his life. The physician became a friend, a supporter, and a knowledgeable liaison to the world of human anatomy.

Intimate knowledge of the human body—such as how its more than two hundred bones

fit together and fall into conflict—let Iyengar refine the poses. The Triangle was a good example. His method avoided subtle misalignments that could restrict movement. The beginner’s pose, known formally as Trikonasana, began in a standing position as the student spread arms and legs far apart and bent the torso to one side, reaching up with one arm and down with the other. The pose was then repeated on the opposite side. The potential conflict centered on the thigh bone and a large knob at its upper end known as the greater trochanter, a spot where muscles attached. As the student bent over, the pelvis could easily strike the knobby protrusion, which stopped all downward movement. The solution was simple. It called for the student to turn the foot ninety degrees so it pointed outward. That rotated the overall leg and turned the greater trochanter backward so that the pelvis and torso were free to sweep downward. The result was a deeper thrust and a better stretch.