The Second Spy: The Books of Elsewhere: Volume 3 (13 page)

Read The Second Spy: The Books of Elsewhere: Volume 3 Online

Authors: Jacqueline West

“I suppose that would be

hand-y

, yes,” said Mrs. Dunwoody.

Both women giggled. Olive thought she might be sick.

“Would you like a short tour?” Mrs. Dunwoody asked.

No! No! NO!!

chanted the voice in Olive’s head.

“Yes!” said Ms. Teedlebaum.

“Let’s start in the library.” Mrs. Dunwoody ushered her guest toward the heavy double doors. “This is one of my favorite paintings in the house…”

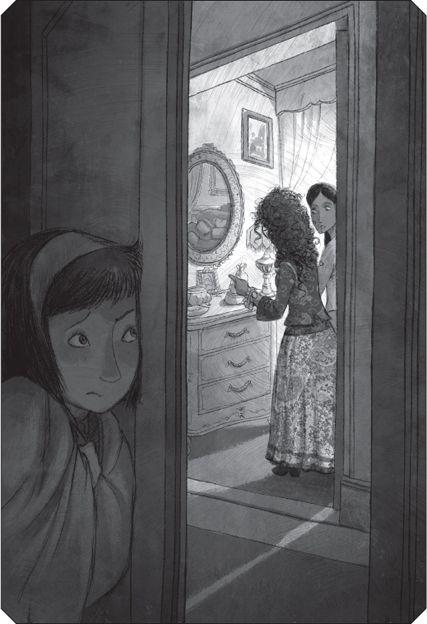

The sound of voices and footsteps and jangling keys faded as the two women walked into the room. Olive remained crouched against the staircase, knowing that they were gazing up at the painting of the dancing girls in the flowery meadow. When they moved into the parlor to look at the French street scene, Olive wriggled across the hall, pressing close to the doorway.

“Lovely,” she could hear Ms. Teedlebaum saying. “Don’t those pigeons look as though they might take flight at any moment?”

They drifted through the dining room and the kitchen, Ms. Teedlebaum gasping and oohing and exclaiming, Olive shuffling surreptitiously behind in her wrapping of blankets. When the women moved toward the stairs, Olive had to hop backward through the parlor doors, hiding in the corner until she heard Ms. Teedlebaum comment on the beautiful light reflected in the silver lake and the details of the bare branches in the moonlit forest.

“There are more down this part of the hall, in the

guest bedrooms,” she heard Mrs. Dunwoody saying. The women stepped into the blue bedroom, and Olive waddled as quickly as she could up the staircase, still wrapped like a pupa in her quilted cocoon.

A moment later, Mrs. Dunwoody and Ms. Teedlebaum reemerged, and Olive leaped through her own bedroom door in time to avoid being seen. Even while she eavesdropped on the conversation in the hallway, Olive couldn’t help but notice that her room had already been stripped of every trace of her ill-fated artwork. The paints, the jars, the handwritten instructions, and even her paintbrushes had vanished. For someone without opposable thumbs, Horatio had certainly been thorough.

“Look at the colors in this still life,” Ms. Teedlebaum was observing. “And what strange fruits. I’m not sure I’ve seen any of these before.”

“I’ve noticed that too,” said Mrs. Dunwoody. “Perhaps they are Victorian varieties that just aren’t cultivated anymore.”

“Or perhaps they’re all mutants,” said Ms. Teedlebaum, as if this was a more reasonable explanation.

“Hmm,” said Mrs. Dunwoody.

The art teacher jingled into the lavender bedroom, where Annabelle’s empty portrait waited. Olive zigged out of her room and into the blue bedroom, crouching behind the door.

“This is interesting,” she could hear Ms. Teedlebaum say. “There’s a painting in this frame, but there’s nothing

in

the painting. It looks like the background was painted, but the foreground was never completed.”

“That’s strange,” Mrs. Dunwoody agreed. “I never noticed that.”

“Perhaps the artist was trying to make some sort of statement…Something about how what

isn’t

there when we expect it to be can be even more powerful than what

is

there.”

Olive clutched the doorknob with both hands. Even wrapped in the blankets, her body shuddered with a wave of sudden cold.

The floor creaked as the women stepped back into the hall.

“Is there a third floor?” Ms. Teedlebaum asked. “The house looks so tall, from the outside…”

If she hadn’t been holding on to the doorknob, Olive might have collapsed completely.

“It’s funny you should mention that,” said Mrs. Dunwoody. “From the height of the house, it’s clear that there

was

a third floor, but its entrance has been walled up or sealed over entirely. We haven’t even found the spot where the entrance used to be.”

Olive let out the breath she’d been holding. It came through her nose in short, shaky puffs.

“Well, thank you so much for letting me look around.

This has been a real pleasure,” said Ms. Teedlebaum, clanking and jingling past the door where Olive hid. Olive watched the puff of kinky red hair descend the staircase, followed by her mother’s much-less-puffy head. She waited until she heard two sets of footsteps on the hallway floor below. Then she waddled out into the hall and down the staircase, clutching her blankets, trying to look as though she’d been up in her room being innocently sick the whole time.

Mrs. Dunwoody glanced up as Olive came down the steps.

“Olive, your teacher brought over an art project for you to finish. Wasn’t that nice of her?”

“Yes,” said Olive, in a sickly croak. “Thank you, Ms. Teedlebaum.”

Ms. Teedlebaum smiled and flapped her hands again. “It was nothing. I hope you feel better soon.”

“I hope you—” said Olive, in knee-jerk fashion, before catching herself. “Um—feel good too.”

Ms. Teedlebaum didn’t seem to find this odd. She just went on smiling. Then she wrapped one of her three scarves back around her neck, setting the cords of keys and trinkets clinking, said “Good-bye!” and jangled out the door.

“What a nice woman,” said Mrs. Dunwoody, closing it behind her.

Leaning her forehead against the front windows,

Olive watched the art teacher’s rusted station wagon bump out of the drive and pull away. Her heartbeat was finally slowing back to its normal rate, but her mind was still whirring along at high speed.

How had Ms. Teedlebaum known about Aldous McMartin’s paintings? Was she only interested in them as

art

…or was she looking for something more? Olive felt the hairs on the back of her neck rise as a new thought shot across her mind: Did Ms. Teedlebaum have something to do with the note from Annabelle that had been planted in the art classroom?

Olive pressed her face to the cool glass, feeling genuinely sick once again. It was just as Annabelle had written—it was hard to know whom to trust. These days, Olive wondered if it was safe to trust anyone at all.

15

O

N SATURDAY MORNING, a strange thing happened.

It wasn’t that Olive managed to find a matching pair of slippers under her bed, although this

was

unusual. And it wasn’t that she both brushed

and

flossed her teeth before she tromped downstairs, although this was also very unusual. It wasn’t even that she remembered all the digits of someone else’s phone number when she picked up the receiver and started dialing, although this was

extremely

unusual. The strange thing was that the phone number she was dialing was Rutherford’s.

Olive dropped the receiver back into its cradle before it could begin to ring.

What was she thinking?

Had she forgotten overnight

that Rutherford was deserting her? Olive stared at the silent telephone, chewing on a strand of her hair. She couldn’t depend on him anymore. She couldn’t tell him about her horrible mistakes with the paints, or about Ms. Teedlebaum’s visit. She would have to face her troubles alone.

Well…maybe not

completely

alone.

Inside the painting of Linden Street, Olive scurried up the hill, displacing puffs of mist that settled swiftly back into place. An old woman in a rocking chair stopped rocking as Olive hurried past. Olive gave a little wave. The woman didn’t wave back. Through dark windows, Olive could feel other eyes watching her—the same eyes that had watched her yesterday, as she led her deformed portraits to Morton’s lawn.

Cheeks burning, Olive tucked her chin to her chest and hurried on.

Morton wasn’t in his yard. He wasn’t on his front porch either. Olive scanned the street all around the tall gray house, but there was no sign of a small boy in a long white nightshirt. She checked the branches of the oak tree. No Morton. She looked behind the shrubs. No Morton.

The door of the tall gray house was shut. Olive knocked, but there was no answer, and when she tried to turn the doorknob, she found that it was stuck firmly in place. It couldn’t be locked, Olive knew,

because nothing inside Elsewhere could be changed without changing quickly back. There was only one way the knob could be held in place: If someone inside was doing the holding.

“Morton?” she called softly, putting her lips to the door. “Morton, I know you can hear me. I have something for you.”

As soon as the words came out of her mouth, Olive realized that they were probably the

last

words she should have said. Morton wouldn’t want any sort of surprises from Olive for a very long time.

The door stayed shut. Morton’s whole house was giving her the silent treatment.

Bending down, Olive took the old black-and-white photograph of Morton’s family out of her pocket and slipped it carefully through the narrow gap beneath the door.

There was a long, quiet moment while Olive stood on the porch, staring at the door. And then, slowly, it creaked open, and Morton’s small white form edged out.

“I thought you might be surprising me with more

parents,

” he said.

Olive gestured to the empty porch. “Nope. No parents. I’m done trying to make anything with Aldous’s paints.”

Morton hung on the doorknob, swinging slowly

back and forth. His tufty white hair drifted back and forth too, like dandelion seeds that wouldn’t blow away. “Do those

cats

know what you did?” he asked.

“What do you mean,

those cats?

” Olive repeated. “You know their names.”

Morton only shrugged and went on swinging.

“No,” said Olive. “Well—Horatio knows. He was really mad. He took the paints and the papers away.”

Morton narrowed his eyes. “Mr. Fitzroy says,” he began, swinging back and forth even faster, “he says…they might not have our best interests at heart.” Morton’s words marched out in the stiff pace of something memorized.

“

Mr. Fitzroy

doesn’t really know them,” Olive said, putting her fists on her hips. “I

told

your neighbors that they could trust the cats.”

Morton stopped swinging. His eyes drifted toward Olive’s toes. “Well—they don’t really trust

you,

either.”

Olive’s mouth opened, but nothing came out. The neighbors knew she had lied about keeping the papers safe. They knew she had used the paints. She had used the neighbors too, taking advantage of their help—and Morton’s—to do something that didn’t help anyone at all. They didn’t trust her. And she wasn’t sure she could blame them.

Morton gazed past Olive’s shoulder. “I bet I can balance on this railing better than you,” he said abruptly,

hopping across the porch and climbing onto its banister.

“I bet you can too,” said Olive.

But Morton decided to prove it anyway. He walked back and forth several times, with both skinny arms sticking straight out, and only fell off into the bushes once. Olive clapped politely when he was done.

“I’m glad you’re still here, Morton,” she said as Morton slid down from the railing.

Morton gave her a frown.

“I mean, I’m not glad that you’re

stuck

here, I just…” Olive trailed off with a sigh. “You remember Rutherford, from two houses away? You met him when Lucinda was hiding Annabelle in her house.” Olive plopped down on the porch steps. “He’s leaving. He’s going to go to a fancy school in Sweden, where his parents are doing research, and I’m going to be stuck in sixth grade all alone.” Olive flicked a fallen oak leaf off of the step and watched it flutter back into its place. “I bet he was just curious about this house. I bet he never actually wanted to be my friend in the first place.”

Morton sat down beside her. He tugged at the hem of his nightshirt until it covered his toes. Then he said, “Maybe he just misses his parents.”

Olive kicked an acorn cap. A moment later it was back in its spot, as though it had never moved at all.

“You have to stay here for three more months, remember,” she said softly. “We made a deal.”

“Three months minus three days,” said Morton.

They were quiet for a minute. Olive leaned forward, holding her chin in both hands. Morton did the same. They both stared across the street at the silent houses on the other side.

“Do you want to go dance in the ballroom?” Olive asked at last.

“Not really,” said Morton.

“Want to play with Baltus?”

Morton shrugged.

“We could explore a new painting. There are some at the other end of the hall that—”

“That’s all right,” Morton interrupted. “I think I’m just going to stay here.”

Slowly, Olive stood up. “Okay,” she said, looking down at the top of Morton’s tufty white head. “I’ll come visit again soon.”

The tufts gave a tiny nod.

Olive waited for another minute before turning away and walking across the lawn into the deserted street.

She passed the empty lot where the old stone house would have stood, if Aldous had painted it there, and was shuffling along yet another quiet lawn when a voice said, “Evening, Miss Olive.”

Olive jumped. The old man with the beard—Mr. Fitzroy, she remembered—strolled toward her through the mist. He gave her a smile, which was half hidden in the bristly kinks of his beard.