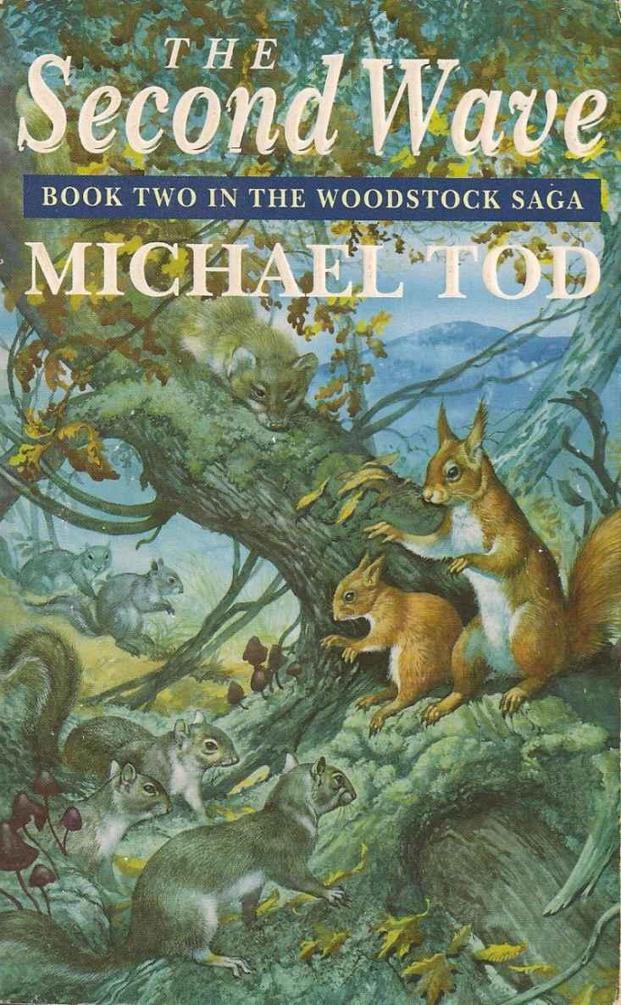

The Second Wave

Authors: Michael Tod

THE SECOND WAVE

Book Two in The Dorset Squirrels Saga

by

Michael Tod

PUBLISHED BY:

Cadno Books

The Dorset Squirrels Saga

Copyright © 2010 Michael Tod

This book is available in print at

michaeltod.co.uk

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, brands, media, and incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. The author acknowledges the trademarked status and trademark owners of various products referenced in this work of fiction, which have been used without permission. The publication/use of these trademarks is not authorized, associated with, or sponsored by the trademark owners.

About the Author.

Novelist, poet and philosopher Michael Tod was born in Dorset in 1937. He lived near Weymouth until his family moved to a hill farm in Wales when he was eleven. His childhood experiences on the Dorset coast and in the Welsh mountains gave him a deep love and a knowledge of wild creatures and wild places, which is reflected in his poetry and novels.

Married with three children and three grandchildren, he still lives, works and walks in his beloved Welsh hills but visits Dorset whenever he can.

CHAPTER ONE

1962

Chip sat on top of the world. At least, that was what it seemed like to him as he looked down from the edge of the cliff. The wind was chill and he wriggled back into the shelter of a rock.

‘Squimp!’ called Crag, his father, in a voice as cold as the wind which tore at his fur. ‘Out from behind that rock. Now!’

Chip, a thin, first-year red squirrel, came out reluctantly and crouched beside his mother, Rusty, keeping as far away as he could from Crag, the Temple Master. He could never be sure of when he would get a cuff across the back of his head and it was as well to stay out of his father’s reach.

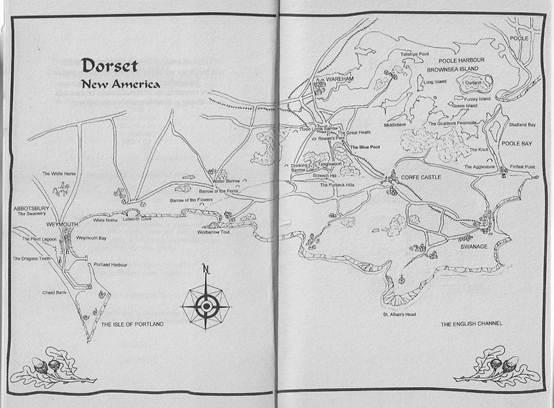

He stood up and followed the gaze of his parents as they studied the panorama below, a gust buffeting him and tugging at his pointed ears where the first tufts were just beginning to show. The squirrels were on the very edge of the north-western cliff-top of Portland. Below him the white stone cliff-face fell away to terraces of tumbled rocks, against which the dark green, gale-driven sea fretted and gnawed. As he watched, a great wave crashed and tore itself to pieces in a weltering mass of foam and spray.

Looking further northwards his eyes followed the golden sweep of the Chesil Beach curving away into the far distance, the September sun glowing on the myriad high-banked pebbles protecting the Fleet Lagoon which lay between the pebble bank and the land. Beyond his father, on his right-paw side, over the jostle of Man-dens on the lower ground, he could see the blue sheltered waters of Portland Harbour where battleships lay at anchor, but Young Chip had no idea what these were. A squirrel youngster has much to learn about the world, especially if he is the only one of his year on the great stone mass which is the Isle of Portland, so windswept that trees are rare, surviving only in hollows and a few other sheltered places.

He watched the blue of the harbour turn to grey as gusts of wind rippled the surface then, as the gold of the Chesil Beach darkened, he looked to his left. A bank of clouds had covered the sun and was racing towards the land trailing a grey veil below it. He knew that in a few minutes a rain squall would reach them, and again turned instinctively for cover. Crag glowered at him, so he turned back, to stare miserably out to sea, shivering. Even the comfortless stone of their den in the cave at the back of the quarry had been preferable to this!

Chip’s world had suddenly changed with the death of his grandfather, Old Sarsen, five days before.

Chip had been with his parents in the Temple Cave, crouched near a mass of rusting scrap iron where the old squirrel lay, wheezing and coughing out his last instructions to Crag and Rusty.

‘Remember your vows,’ the old squirrel had said. ‘

You

are nothing. The Sun is everything. Worship and serve it, or it’ll be the Sunless Pit for both of you. For ever!’

Chip could still hear the intensity of expression in his grandfather’s voice. ‘You there, you, young one, remember this – serve the Sun. The Sun is everything. Fear the Sun and

dread

the Sunless Pit.

Chip could recall the shudders of terror which had engulfed him. The thought of never seeing the sun again had terrified him, and even now his stomach churned with the thought.

‘You will all have to leave Portland,’ his grandfather had told them. ‘The Sun punished all unworthy squirrels by denying them dreylings. They were too idle to collect the sacred metal as we all do, so the Sun in its wisdom denied them issue. There are only four of us left here now and the youngster will need to mate next year. Go to the Mainland. Carry the True Word. Serve the Sun.’

‘What about the Temple?’ Crag had asked.

‘You will have to leave it. It will still be here if you can ever return.’

The old squirrel had scrabbled at the stone floor, his blunt claws slipping on the rock, worn smooth by the feet of generations of his ancestors, until with one last effort he had hauled himself to the top of the pile of metal, the rattle of empty tins echoing around the hollow of the cave. Then, in the silence that followed, he called –

‘Sun, I’ve served you well.

Take me to you. Save me from –

That dread Sunless Pit!’

An agonised look had crossed his face and his lifeless body had tumbled down the pile to sprawl at Chip’s feet.

Showing no trace of emotion, Crag had ordered Rusty and Chip to help him drag the scraggy body up the rock face, to one of the drill holes left when the quarry was abandoned. Here they had slid it, head first, down the hole, to join the bones of Old Sarsen’s father and those of his father before him. Death must be as uncomfortable as life if a squirrel was to avoid the Sunless Pit, the youngster had thought.

A seagull whirled past Chip’s head, squawking as it was tossed on the updraught of the wind striking the cliff-face, and a kestrel that had been hovering turned away inland and dropped between the mass of rocks behind them. Out over the sea, the rain clouds were much nearer.

‘We go down,’ Crag ordered.

Chip gave a last look at the wrinkled sea below and at where the waves twisted over themselves as they ran along the curve of the Chesil Beach, then followed his parents onto the vertical face of the rock.

The wind buffeted him, but he climbed down head-first, confidently finding claw-holds in the tiniest of cracks and crevices. As Mainland squirrels were totally at home in trees, so was he on rock; neither he nor any of his family had ever climbed a tree.

He had once seen a tattered sycamore in a sheltered hollow whilst searching for metal with his grandfather and had moved towards it, drawn by this exciting living thing which created such a strange craving within him, but Old Sarsen had ordered him to leave it alone. ‘Shut your eyes to the temptation,’ he had been told. ‘We will search this way.’ And the old squirrel had led the youngster off between the rocks away from the sin-provoking tree.

These long-abandoned quarries, though eerie places to humans, were quite familiar to Chip and his family. Huge blocks of substandard rock had been stacked in heaps, or scattered about as though by the paws of some giant squirrel, and over and around these wild cotoneaster bushed trailed, their green foliage now covered by blood-red berries. Large snails, their grey shells banded with a darker whirl, grazed on the leaves, and grasshoppers, safe here from lowland farmers’ pesticides, chirred and chirruped amongst the yellow-flowered ragwort and the purple valerian. Above the squirrels the spiky dry seed heads of teasels had patterned the skyline.

In the quarry-waste they had found an old pick head, flaking into layers of rust, but, despite the combined efforts of the old squirrel and the youngster, they had been unable to do more than drag it to the bottom of the cliff below the Temple Cave. There they had had to leave it, lying amongst the harts-tongue ferns, a constant reminder of how feeble they were, compared with the might of the Sun above.

A moon or so ago Chip had asked his mother about the metal collecting. At first she had seemed reluctant to speak of it. Then, when just the two of them were out searching and had found nothing, she had spoken unguardedly in frustration.

‘I’m sure the Sun doesn’t want all this stuff,’ she had said. ‘It was your great-grandfather, Monolith, who started it all. He was the chief of all the Portland squirrels then and a miserable old creature he was by all accounts. I never found out what sin he did that was so awful that he thought he had to punish himself this way. Metal collecting is a bore and it hurts our teeth and I hate the whole stupid business!

‘Even worse, he taught your grandfather to do it and

he

taught your father. Now

he’s

teaching you. When will it ever stop? Why in the name of the Sun do we have to suffer for something Old Monolith did that everyone has forgotten long ago?’

Chip had stared at his mother. She had never spoken like this before – he did not know what to say.

Rusty continued, the words tumbling out. ‘My brother, your uncle, said that the problem with living isolated on islands is that extreme ideas get more and more exaggerated.’

Chip had wondered what ‘exaggerated’ meant. He raised his tail into the query position and was about to ask, when his mother said, ‘He died last year with no dreylings to follow him. I do miss him.’

Rusty had looked tired and worn, and Chip had moved across to comfort her, but she had waved him away.

‘I shouldn’t have said that,’ she had told him. ‘For the Sun’s sake, and mine, don’t repeat it. Come on, we must find

something

.’

They had searched all day, quartering the stone slabs of the quarry floor, raking with their claws through every tuft of grass and peering into each crack and hole between the stones, but had returned to the cave with only a crown-cap from a discarded bottle between them, to the disgust of Old Sarsen, the Temple Master.

Once Chip had complained that it hurt his teeth to drag rusty tins along the stony paths of the abandoned quarries, and the stern old squirrel had said, ‘That’s one of the reasons why we do it. The discomfort is good for you.’