The Second World War (37 page)

Read The Second World War Online

Authors: John Keegan

Paulus mounted a final effort on 11 November, in weather that already heralded the cold which would freeze the Volga and restore Chuikov’s solid passage to the far shore. Next day a thrust by the Fourth Panzer Army succeeded in reaching the Volga south of the city, thus encircling it completely. That was the last success the Germans were to achieve at this easternmost point of their advance into Russia. For six days local and small-scale battles flickered on, killing soldiers on both sides but gaining ground for neither. Then, on 19 November, in Alan Clark’s words ‘a new and terrible sound overlaid’ the rattle of small arms – ‘the thunderous barrage of Voronov’s two thousand guns to the north’. The Stalin-Zhukov-Vasilevsky counter-stroke had begun.

In order to concentrate the largest possible German force against Stalingrad itself, Hitler had economised elsewhere by lining the Don over the steppe front north and south of the city with his satellite troops, Romanians, Hungarians and Italians. The kernel of his Stalingrad concentration, in short, was German; the shell was not. All autumn Hitler had blinded himself to this weakness in the

Ostheer

’s deployment. Now the Russians detected that, by breaking the fragile shell, they would surround and overcome the Sixth Army without having to fight it directly. It was about to suffer an encirclement by which Stalin would gain partial revenge on Hitler for those at Minsk, Smolensk and Kiev which had nearly destroyed the Red Army the previous year.

Zhukov’s plan disposed two fronts, South-West (Vatutin) and Don (Rokossovsky), west of the city with five infantry and two tank armies, and the Stalingrad Front (Yeremenko) to the south with one tank and three infantry armies. The South-West and Don Fronts struck on 19 November, the Stalingrad Front the following day. By 23 November their pincers had met at Kalach on the Don west of Stalingrad. The Third and Fourth Romanian Armies had been devastated, the Fourth (German) Panzer Army was in full retreat, and the Sixth Army was entombed in the ruins on the banks of the Volga.

The inception of Operation Uranus (as the Russians codenamed their counter-offensive) found Hitler at his house at Berchtesgaden, in retreat from the strains of fighting the Russian war. He at once took the train to Rastenburg, where he met Zeitzler on 23 November and, in the teeth of his chief of staff’s advice that the Sixth Army must withdraw or be destroyed, peremptorily issued the disastrous order: ‘We are not budging from the Volga.’ During the next week he cobbled together the expedients that would keep the Sixth Army there. The Luftwaffe would supply it: Paulus’s statement that he needed ‘700 tons’ of supplies a day was ‘realistically’ assumed to mean 300, and the figure of 60 tons currently reaching the city in twenty to thirty Junkers 52 was multiplied by the theoretical availability of aircraft to match that figure. Manstein, the armoured-breakthrough magician, would relieve it; the reserves he would need were said to be available for an operation, ‘Winter Storm’, that would begin in early December. In the meantime Paulus was not to break out. At most, when Manstein’s attack developed, he was to reach out towards him (on receipt of the signal ‘Thunderclap’) so that the Don-Volga bridgeheads could unite to form the same threat to the Red Army they had constituted before the counter-attack of 19-20 November.

Manstein, as commander of the newly formed Army Group Don, disposed of four armies for ‘Winter Storm’: the Third and Fourth Romanian, the Sixth (German) and the Fourth Panzer. The first two, always defective in equipment and commitment, were now broken reeds; the Sixth Army was imprisoned; the Fourth Panzer Army could still manoeuvre but had only three tank divisons, 6th, 17th and 23rd, to act as a spearhead. The attempted breakthrough began on 12 December. The Panzer divisions had some sixty miles of snow-covered steppe to cross before they could reach Paulus’s lines.

Until 14 December they made good progress; a measure of surprise had been achieved and the Russians, now as ever, found it difficult to resist the initial impetus of a German advance. Time might be on their side but they could not match the Wehrmacht in military skill. Against the Wehrmacht’s satellites, however, they were on equal if not better terms. On 16 December the Italian Eighth Army north of Stalingrad, which had thus far escaped the Romanians’ fate, was struck and penetrated and a new threat was hurled against Manstein’s Panzer thrust. On 17 December the 6th Panzer Division lurched to within thirty-five miles of Stalingrad, close enough to hear gunfire from the city; but the pace of advance was slowing, the Italian front was bending and the Sixth Army showed no sign of reaching out to join hands. On 19 December Manstein flew his chief intelligence officer into the city in an effort to galvanise its commander. He returned with news that Paulus was oppressed by the difficulties and the fear of incurring the Führer’s disfavour. On 21 December Manstein tried but failed to persuade Hitler to give Paulus a direct order for a break-out. By 24 December his own relief effort had ground to a halt in the snows of the steppe between the Don and Volga and he could only accept the necessity to retreat.

Retreat, too, was a consequent necessity for Kleist’s dangerously overextended Army Group A in the Caucasus. The previous autumn his motorised patrols had reached the shore of the Caspian Sea, the Eldorado of Hitler’s strategy, but had turned back near the mouth of the river Terek for lack of support. In early January the whole of the First Panzer and Seventeenth Armies began to withdraw from the Caucasus mountain line, and retire through the 300-mile salient created by their headlong dash south-eastward the previous summer. As late as 12 January, Hitler still hoped to hold the Maikop oilfields. When Russian pressure north of Stalingrad cast the Hungarian Second Army into disarray, he was obliged to transfer the First Panzer Army to Manstein to augment his armoured strength. Nevertheless he directed Kleist, whose Army Group A was now shrunk to a single army, the Seventeenth, to withdraw it into a bridgehead east of the Crimea from which he hoped offensive operations could be resumed when the Stalingrad crisis ameliorated.

The hope was quite illusory. During January the German defence of Stalingrad was expiring by inches. Daily deliveries by the Luftwaffe to the three airfields within the perimeter averaged 70 tons; on only three days of the siege (7, 21 and 31 December) did deliveries exceed the minimum of 300 tons needed to sustain resistance. In the first week of January 1943 the forward airfield at Morozovskaya was overrun by Russian tanks; thereafter Richthofen’s Ju 52s – diminished in number by the transfer of some to fly paratroops to Tunisia – had to operate from Novocherkassk, 220 miles from Stalingrad. After 10 January, when the main airstrip inside the Stalingrad perimeter fell, landing became difficult, most supplies were airdropped and the wounded could no longer be regularly evacuated. By 24 January nearly 20,000 men, one-fifth of the entombed army, were lying in makeshift, often unheated hospitals, with the outside temperature at minus 30 degrees Centigrade.

On 8 January, Voronov and Rokossovsky sent Paulus a summons to surrender, promising medical care and rations. ‘The cruel Russian winter has scarcely yet begun,’ they warned. Paulus, who had refused Manstein’s appeal to break out three weeks earlier for fear of offending the Führer, could not contemplate such an act of disobedience. The terrible struggle continued. On 10 January the Russians opened a bombardment with 7000 guns, the largest concentration of artillery in history, to break the Sixth Army’s line of resistance. By 17 January its soldiers had been forced back into the ruins of the city itself, by 24 January the army had been split into two, and the next day the Russian forces on the eastern shore of the river crossed the Volga and joined Chuikov’s Sixty-Second Army stalwarts in their pockets around the Barricades and Red October factories.

Hoping for a gesture of honourable defiance, Hitler promoted Paulus to field marshal’s rank by signal on 30 January. No German field marshal had ever surrendered to the enemy and he thus ‘pressed a [suicide’s] pistol into Paulus’s hand’. At this final imposition of authority Paulus baulked. On 30 January his headquarters were overrun and he surrendered with his staff to the enemy. The last survivors capitulated on 2 February, leaving 90,000 unwounded to 20,000 wounded soldiers in Russian hands. ‘There will be no more field marshals in this war,’ Hitler announced to Zeitzler and Jodl on 1 February at Rastenburg. ‘I won’t go on counting my chickens before they’re hatched.’ Rightly he predicted that Paulus ‘will make confessions, issue proclamations. You’ll see.’ (Paulus would indeed lend himself to Stalin’s Committee of Free German Officers, which would call on the

Ostheer

to cease resistance and work for a Russian victory.) ‘In peacetime in Germany about 18,000 to 20,000 people a year choose to commit suicide,’ Hitler continued, ‘although none of them is in a situation like this, and here’s a man who has 45,000 to 60,000 of his soldiers die defending themselves bravely to the end – how can he give himself up to the Bolsheviks?’

The official reaction to the Stalingrad disaster was altogether more measured. German losses between 10 January and 2 February had in fact totalled 100,000, and few of the 110,000 captured survived transport and imprisonment. For three days normal broadcasting by German state radio was suspended and solemn music, Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony, transmitted instead. Hitler, advised by Goebbels, saw in the destruction of the Sixth Army and its twenty-two German divisions an opportunity at least to create a national epic. There was no need for the fabrication of epic in Russia. On the news of Paulus’s surrender the bells of the Kremlin were rung to celebrate the first undeniable Russian victory of the war. The Sixty-Second Army was redesignated the Eighth Guards Army, and Chuikov, a future Marshal of the Soviet Union, entrained it the following month for the Donetz. ‘Goodbye, Volga,’ he recalled thinking as he left Stalingrad, ‘goodbye the tortured and devastated city. Will we ever see you again and what will you be like? Goodbye, our friends, lie in peace in the land soaked with the blood of our people. We are going west and our duty is to avenge your deaths.’ When next Chuikov and his soldiers fought a battle for a city, it would be in the streets of Berlin.

THE WAR IN

THE PACIFIC

1941-1943

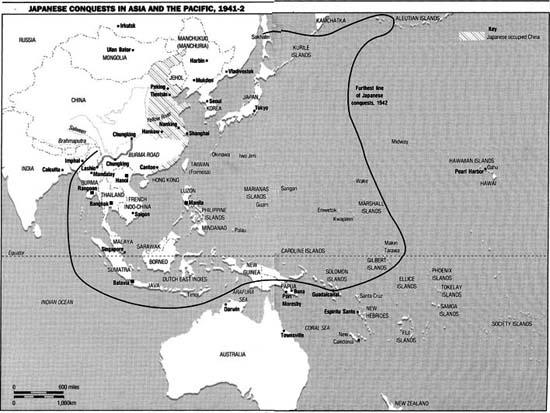

Throughout the second year of his war on Russia, Hitler had laboured under a separate and self-assumed strategic burden: war with America. At two o’clock in the afternoon of 11 December 1941, four days after General Tojo’s government in Tokyo had unleashed Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Ribbentrop, as Foreign Minister, read out to the American chargé d’affaires in Berlin the text of Germany’s declaration of war on the United States. It was an event which Ribbentrop, in perhaps his only truly sagacious contribution to Nazi policy-making, had struggled to avoid. During the period of American neutrality Hitler too had shrunk from acts which might provoke the United States to war against him. Now that Japan had cast the die, he hastened to follow. Ribbentrop emphasised, in vain, that the terms of the Tripartite Pact bound Germany to go to Japan’s assistance only if Japan were directly attacked. On hearing the news of Pearl Harbor Hitler raced to tell it to Jodl and Keitel, exulting that ‘Now it is impossible for us to lose the war: we now have an ally who has never been vanquished in three thousand years.’ (Churchill, on hearing the same news, came to an identical but contrary conclusion: ‘So we had won after all.’). On 11 December Hitler convoked the Reichstag and announced to the puppet deputies: ‘We will always strike first! [Roosevelt] incites war, then falsifies the causes, then odiously wraps himself in a cloak of Christian hypocrisy and slowly but surely leads mankind to war. . . . The fact that the Japanese government, which has been negotiating for years with this man, has at last become tired of being mocked by him in such an unworthy way, fills all of us, the German people, and, I think, all other decent people in the world with deep satisfaction.’ Later that day Germany, Italy and Japan renewed the Tripartite Pact, contracting not to conclude a separate peace nor to ‘lay down arms until the joint war against the United States and England reaches a successful conclusion’. Privately Ribbentrop warned Hitler: ‘We have just one year to cut Russia off from her military supplies arriving via Murmansk and the Persian Gulf; Japan must take care of Vladivostok. If we don’t succeed and the munitions potential of the United States joins up with the manpower potential of the Russians, the war will enter a phase in which we shall only be able to win it with difficulty.’

This view was not only the opinion of a member of Hitler’s entourage whose reputation was in eclipse. It was also held by a Japanese commander at the centre of his country’s policy-making. In late September 1940 Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto, Commander of the Combined Fleet, had told the then Prime Minister, Prince Fumimaro Konoye: ‘If I am told to fight regardless of the consequences, I shall run wild for the first six months or a year, but I have utterly no confidence for the second or third year. The Tripartite Pact has been concluded and we cannot help it. Now the situation has come to this pass [that the Japanese cabinet was discussing war with the United States], I hope that you will endeavour to avoid a Japanese-American war.’ Other Japanese had a fear of war, Konoye among them; the opinion of none of them carried the weight of the admiral at the head of Japan’s operational navy. How did it come about not only that his views were overruled but that, less than a year after he expressed his anxieties to Konoye, he should, against his better judgement, have been planning the attack which would commit his country to a life-and-death struggle with a power he knew would defeat it?