The Second World War (9 page)

Read The Second World War Online

Authors: John Keegan

Dietl, though in many respects the least successful of the German generals of 1939-40, was to become Hitler’s favourite; his death in an aeroplane crash in June 1944 was regarded by the Führer as a wounding personal tragedy. By then he had come to regard Dietl as irreplaceable and he attempted to conceal the news of his death from the Finns, among whom Dietl had established a towering reputation during the Finnish ‘Continuation War’ of 1941-4, lest it discourage them further at a time when defeat by the Russians again stared them in the face. Hitler liked Dietl because he argued with him in an explosive, soldierly way that perhaps reminded the Führer of his own army service. He liked him even more because at Narvik he had rescued him from humiliation. So alarmed had Hitler been by the miscarriage of the landing that he had been on the point of ordering Dietl to escape into Sweden and intern his soldiers rather than risk having to surrender them to the British. He had eventually been dissuaded from sending the signal, and in any case Dietl’s dogged conduct of the siege and retreat made it unnecessary. Dietl was the model of what Hitler wished every German soldier to be, the type he had looked forward to recruiting and training in thousands from the moment he embarked on the creation of the Wehrmacht. The proof of his quality was his snatching of victory from the jaws of defeat in the mountains of north Norway in June 1940, and so sustaining unblemished the record of German military success since the beginning of the war. To the campaign simultaneously unfolding in the west, however, not even a Dietl could have added a jot to the dimensions of German victory. There

Blitzkrieg

seemed a magic which had taken possession of the army itself.

THE WAR IN

THE WEST

1940-1943

Blitzkrieg

Blitzkrieg

– ‘Lightning War’ – is a German word but not known to the German army before 1939. A coining of Western newspapermen, it had been used to convey to their readers something of the speed and destructiveness of German ground-air operations in the three-week campaign against the ill-equipped and outnumbered Polish army. However, as the German generals themselves readily conceded, the Polish campaign had not been a fair test of the army’s capabilities. Despite allegations by some of them that the Wehrmacht had not shown itself the equal of the old imperial army – allegations which drove Hitler to a frenzy of rage against General Walther von Brauchitsch, the commander-in-chief, at a meeting in the Reich Chancellery on 5 November – the plodding Polish infantry divisions had offered no match to the mechanised spearheads of Guderian and Kleist.

Blitzkrieg

aptly described what had befallen Poland.

Would

Blitzkrieg

avail against the West? Hitler persisted into October in hoping that its spectacle would persuade France and Britain to accept his Polish victory; but their rejection, on 10 and 12 October respectively, of his peace tentatives, offered in a speech to the Reichstag on 6 October, persuaded him that Germany must make war again. His ambitions required at least the defeat of France, which might persuade Britain to sue for separate terms and inaugurate that accommodation of her maritime with his continental empire for which his upbringing as a subject of the old landlocked Danubian empire led him unrealistically to hope. On 12 September he had told his Wehrmacht adjutant, Rudolf Schmundt, that he believed France could be conquered quickly and Britain then brought to negotiate; on 27 September he warned the commanders-in-chief of the three services that he intended to attack in the west shortly; and on 9 October, even before France and Britain had rejected his peace offer, he issued Führer Directive No. 6 for a western offensive.

In an accompanying memorandum, which accused France and Britain of having kept Germany weak and divided since the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, he announced that nothing less was at stake than ‘the destruction of the predominance of the Western powers in order to leave room for the expansion of the German people’. Führer Directive No. 6 described how that destruction was to be achieved:

An offensive will be planned . . . through Luxembourg, Belgium and Holland [and] must be launched at the earliest possible moment [since] any further delay will . . . entail the end of Belgian and perhaps of Dutch neutrality, to the advantage of the Allies. The purpose of this offensive will be to defeat as much as possible of the French army and of the forces of the Allies fighting on their side, and at the same time to win as much territory as possible in Holland, Belgium and northern France to serve as a base for the successful prosecution of the air and sea war against England and as a wide protective area for the economically vital Ruhr.

The plan of attack, codenamed

Fall Gelb

(‘Case Yellow’), was to be worked out in detail by the high command of the army, the

Oberkommando des Heeres

(OKH). Although Hitler as Supreme Commander laid down broad strategic aims, he did not as yet involve himself in technical military affairs. Hitler nevertheless had strong if not clear ideas of what he wanted ‘Case Yellow’ to achieve. Here was to be the making of a strategic imbroglio which would set Führer and army at loggerheads for the next five months. Historically the German army, and the Prussian army before it, had always deferred to the fiction that the head of state was warlord –

Feldherr

. However, not since Frederick the Great had led his soldiers in person against those of the tsar and the Holy Roman Emperor had a head of state actually interfered in his generals’ planning. Kaisers Wilhelm I and II, at the onset of war with France in 1870 and 1914, had transferred their courts to the army’s headquarters; but they had both then surrendered detailed control of operations to their chiefs of staff – the Moltkes, Falkenhayn and Hindenburg in sequence. Hitler would have been willing to do the same had the successors of those men shared his vision of what the reborn German army could, with the Luftwaffe, achieve; but the commander-in-chief, Brauchitsch, was a doubter and his chief of staff, General Franz Halder, a quibbler. Halder was a man of brains, a product of the Bavarian General Staff Academy whose graduates were thought intellectually more flexible than those of the Prussian

Kriegsakademie

. His war experience, however, had been as a staff officer employing the step-by-step tactics of the Western Front; his original arm of the service had been the artillery, also dominated by step-by-step thinking; and he was a devout member of the State Lutheran Church and thereby conditioned to recoil from Hitler’s brutal philosophy of domination, national and international, yet not to defy constituted authority by opposing it. As a result, he proposed a form for ‘Case Yellow’ which, as he admitted elsewhere, would postpone the mounting of a decisive offensive against France until 1942. As outlined on 19 October, his plan was designed to separate the British Expeditionary Force from the French army and to win ground in Belgium which would provide airfields and North Sea ports for the German navy’s and air force’s operations against Britain, but not to achieve outright victory.

Thus he acquiesced in the letter of Führer Directive No. 6 but succeeded in denying its spirit. The expedient temporarily baffled Hitler, who lacked allies among the military establishment able to help him argue against Halder. On 22 October he unsettled his chief of staff by demanding that ‘Case Yellow’ begin as soon as 12 November; on 25 October he confronted Brauchitsch with the suggestion that the army attack directly into France instead of northern Belgium; and on 30 October he proposed to General Jodl, his personal operations officer, that the Wehrmacht’s tanks be flung into the forest of the Ardennes, where the French would least expect them. Without expert military support to endorse these proposals, however, he could not jog ‘Case Yellow’ forward.

General Staff resistance rested on solid ground. Late autumn was no season for undertaking offensive operations, least of all on the sodden plains of rainy northern Europe. The Ardennes, even if its narrow valleys led directly to the open French countryside north of the fortified zone of the Maginot Line, was not the obvious terrain for the deployment of tanks. Hitler’s wishes therefore seemed beggars looking for horses to ride – until Halder’s plan came the way of fellow professionals and their rejection of its limitations reached Hitler’s ear. The process took time, time which saved any revision of ‘Case Yellow’ from miscarrying, and it resulted ultimately in a fruitful outcome; for Halder was right to argue that late autumn was the wrong season for the attack on France but mistaken in believing that a bold strategy would not yield large results.

The professionals who took Hitler’s side were the commander-in-chief of Army Group A, Gerd von Rundstedt, and his chief of staff, Erich von Manstein. The significance of Rundstedt’s defection from the General Staff plan was his degree of influence, as one of the most senior generals in the army and commander of the strongest concentration of force on the Western Front. The significance of Manstein’s opposition to Halder’s ‘Case Yellow’ was that he enjoyed Rundstedt’s support and possessed one of the best military minds in the Wehrmacht. At the outset he knew nothing of Hitler’s dissatisfactions with Halder’s plan. It merely affronted him as a half-hearted approach to a problem that instinct told him was susceptible of a full-blooded solution. As autumn weather worsened into winter, however, his instinct led him to advance one criticism after another of the Halder plan, each converging as if by steps in blind-man’s-buff with Hitler’s desires for the outcome of ‘Case Yellow’, and each at the same time laying the foundations for what would come to be called ‘the Manstein plan’.

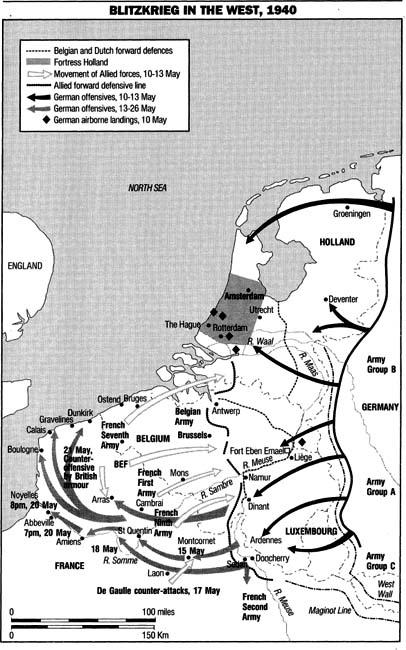

On 31 October the first of six memoranda he was to write arrived at OKH. It argued that the aim of ‘Yellow’ must be to cut off the Allied forces by a thrust along the line of the Somme, thus chiming in with Hitler’s idea of 30 October for an attack through the Ardennes. Brauchitsch, the commander-in-chief, rejected it on 3 November but conceded that more armour should be allotted to Rundstedt’s Army Group A. Meanwhile, as bad weather forced one postponement of the Halder plan after another, Hitler vented his rage in person against his generals for their half-heartedness. He was determined on victory, he warned at the Reich Chancellery on 23 November, and ‘anyone who thinks otherwise is irresponsible’. Manstein called support from other middle-rank professionals, notably Guderian, the tank expert, to endorse his conception of a knockout blow into northern France. Even discounting the possibility that the French and British would do him the favour of throwing too strong forces into Belgium – precisely what they were contemplating, though he could not know that – he was moving over more certainly to the conviction that a drive to divide the enemy forces along the line of the Somme was the correct strategy. Guderian’s assurance that a tank force, if made strong enough, could negotiate the Ardennes, cross the Meuse and deliver the knockout blow reinforced him in that view.

Hitler, despite his differences with Halder, was still allowing his urge to victory to overcome his doubts in Halder’s plan. ‘A-Days’, which would have set it in motion, were fixed four times in December and a final one for 17 January 1940. On 10 January, however, two Luftwaffe officers crash-landed in Belgium with parts of the ‘Yellow’ plan in a briefcase. Enough survived after their attempts to incinerate the documents, the German military attaché to Holland discovered, to compromise the offensive and to oblige the army to make a clean breast of things to Hitler. After his rage subsided – it resulted in the dismissal of the commander of the Second Air Fleet and his replacement by Albert Kesselring, who was to prove one of the most talented German generals of the war – Hitler postponed ‘Yellow’ indefinitely and demanded a new plan ‘to be founded particularly on secrecy and surprise’.

Here was Manstein’s opening. However, the last of his six memoranda had so tried Halder’s patience that he had arranged in December for Army Group A’s chief of staff to be given command of a corps, a theoretical promotion but, since the corps was in East Prussia, an effective dismissal of his troublesome junior from a post of influence. Protocol required, however, that corps commanders on appointment should pay their respects to the head of state. The ceremony ought to have been a formality; but on this occasion chance took Schmundt, Hitler’s Wehrmacht adjutant, by Manstein’s Coblenz headquarters where he got wind of the Manstein plan. It so uncannily matched the Führer’s aspiration, though in a ‘significantly more precise form’, that he ensured Manstein should have a whole morning with the Führer on 17 February. Hitler was entranced, converted, and thereafter did not rest until Brauchitsch and Halder too had accepted the Manstein plan – which he passed off as his own conception.

OKH then demonstrated its institutional strengths. The direct descendant of the old Prussian Great General Staff, it worked merely as the handmaiden of a strong master. Hitler had thitherto shown the strength of will but not of mind to call forth its talents. Now that it had a clear expression of its master’s voice, it concentrated all its efforts on transforming the elements of the Manstein-Hitler conception – for an attack by strong armoured forces through the Ardennes forest into the rear of the Franco-British field army north of the Somme – into a detailed and watertight operation order. It worked fast. Only a week after Hitler’s morning of enlightenment by Manstein, it produced a proposal, codenamed

Sichelschnitt

, ‘Sickle Stroke’, which was a transformation of their half-formed ideas. The theme of its plan was a reversal of Schlieffen’s from 1914. That great chief of staff – already dead by the time his conception was tested on the field of battle – had based his victory plan on the expectation that the French would push into Germany south of the Ardennes, allowing the German armies to outflank them through Belgium. ‘Sickle Stroke’ was based on the expectation that in 1940 the French, with their British allies, would push into Belgium, allowing the German armies to outflank them through the Ardennes. It was a brilliant exercise in double-bluff, all the more so because it reinsured against the expectation’s miscarrying. For, even if the Franco-British army did not push into Belgium, the unexpectedness of the Ardennes thrust and the power and mass of the armoured force with which it was to be mounted promised an excellent chance of catching the enemy in the rear and toppling him off-balance.