The Second World War (107 page)

On 24 January, General T j

j restricted the objective to the destruction of American airfields and the Emperor gave his assent. But the idea of securing a corridor from Manchuria down through China all the way to Indochina, Thailand and Malaya remained very much in the forefront of the general staff’s thinking. American air supremacy over the South China Sea combined with attacks by US submarines threatened to sever maritime connections. A land route was therefore seen as vital.

restricted the objective to the destruction of American airfields and the Emperor gave his assent. But the idea of securing a corridor from Manchuria down through China all the way to Indochina, Thailand and Malaya remained very much in the forefront of the general staff’s thinking. American air supremacy over the South China Sea combined with attacks by US submarines threatened to sever maritime connections. A land route was therefore seen as vital.

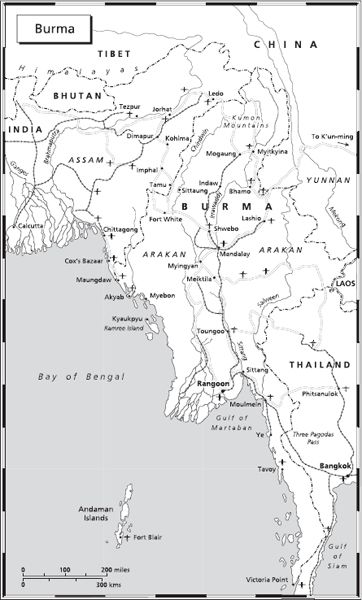

In Burma, both sides were preparing their own offensives. Lieutenant General Mutagachi Renya, the commander of the Japanese 15th Army in Burma with 156,000 men, had become obsessed with invading India. Other senior Japanese officers, especially those with the 33rd Army in north-east Burma, were very sceptical. They wanted to attack the Chinese Nationalists across the Salween River from the west and destroy the US air base at K’un-ming.

The British tend to see the Burma campaign of 1944 as one of Chindit columns deep in the jungle, and the brave defensive battles of Imphal and Kohima under Slim’s leadership turning defeat into victory. Americans, if they think of Burma at all, conjure up images of ‘Vinegar Joe’ Stilwell and Merrill’s Marauders. For the Chinese, it was the Yunnan–north Burma campaign. Their best divisions played a major role here, when they should have been used to defend southern China against the Ichig Offensive, which destroyed Nationalist power and helped the Communists to win the civil war to come.

Offensive, which destroyed Nationalist power and helped the Communists to win the civil war to come.

On 9 January Indian and British troops from the Fourteenth Army, having advanced down the Arakan coast, captured Maungdaw. Once again they wanted to take the island of Akyab with its airfield, but once again they were forced to retreat when the Japanese 55th Division threatened to cut them off. Stilwell, meanwhile, was advancing into north-east Burma with the Chinese divisions in X-Force, which had been trained and equipped by the Americans in India. His plan was to seize the communications centre of Myitkyina, with its airfield. The Allies wanted to eliminate the Japanese air base there because its aircraft threatened the most direct air route to China over the Himalayan Hump. And once Myitkyina had been secured, the Ledo Road could be joined up with the Burma Road to provide a land route once more to K’un-ming and Chungking. The thrust south of the Chinese divisions in X-Force was also designed to join up with the Chinese Expeditionary Force, usually known as Y-Force, attacking from Yunnan across the Salween River into Burma.

Y-Force had just under 90,000 men, less than half its planned strength. A shortage of weapons and equipment was mainly to blame. Chennault’s Fourteenth Air Force took the vast bulk of the supplies air-freighted over the Hump, and since there was a frequent shortfall in the planned deliveries of 7,000 tons a month, the Chinese divisions received little. Stilwell compared the task of rearming them to ‘

trying to manure

a ten-acre field with sparrow shit’. Relations between Chennault and Stilwell had deteriorated even further. Chennault, in an attempt to justify his supply priority, claimed that his aircraft had sunk 40,000 tons of Japanese shipping in the summer of 1943, when the true figure was just over 3,000 tons.

Stilwell’s command in the north-east had been increased by the only

American combat formation on the mainland of Asia. This was the 5307th Provisional Regiment, codenamed Galahad, and dubbed ‘Merrill’s Marauders’ by a journalist after their commander Brigadier General Frank Merrill. The combined chiefs of staff in Washington had been so impressed by Orde Wingate that they had authorized an American version of the Chindits. Loyal tribesmen from the north-eastern highlands known as the Kachin Rangers scouted for them as they did for British imperial troops.

Stilwell’s forces had pushed back the experienced Japanese 18th Division in the Hukawng Valley, but failed to trap it. The Japanese retreat accelerated, however, when Wingate’s Chindits landed in gliders on 5 March well to the south and cut the railway to the Japanese base and airfield at Myitkyina. Operation Thursday was the most ambitious deep-penetration offensive of the war in the Far East. It was far better prepared and supported than the Chindits’ first foray behind Japanese lines.

The 16th Brigade commanded by Brigadier Bernard Fergusson would suffer a ‘

very tedious

’ march from Ledo to Indaw. It was 360 kilometres as the crow flies, but there was never a straight line over high hills and through thick jungle, where they seldom saw the sky. One stretch of fiftyfive kilometres took them seven days. Tropical downpours meant that rivers and streams were swollen and the Chindits ‘

remained wet for weeks

’. ‘

There were four thousand men

,’ Fergusson observed, ‘and seven hundred animals strung out sixty-five miles from end to end, one abreast, because the paths and tracks were not wide enough.’

Two other brigades and another two battalions were flown in by glider and C-47 transports once airfields had been cleared in the jungle. This was done with light bulldozers transported in large American Waco gliders. Mules, 25-pounder field guns, Bofors anti-aircraft guns and all the other heavy equipment also came in by air. One frenzied mule had to be shot dead on the flight out in a C-47 transport, but most casualties had occurred in crash-landed gliders from the first wave. Wreckage was just pushed to the side of the airfield by a bulldozer and left there with the bodies rotting inside, because nobody had time to bury them. It was not an encouraging smell for later arrivals.

Once the airstrips were prepared, the perimeters of these jungle bases were secured with barbed wire and defensive positions ready for the inevitable Japanese counter-attacks. A brigade headquarters staff officer commented that ‘

it was extraordinary

to be landing at night in a Dakota on a strip with a lit flare-path in enemy territory’. The Japanese attacks became suicidally methodical, because they almost always came at the same point and at the same time. Out of pride, they would continue to try again and

again, however many men they lost. Machine-gun posts mowed them down on the wire time after time, and their corpses hanging there attracted swarms of flies.

Soon RAF Hurricanes were operating out of Broadway, the largest base. On 24 March an American B-25 landed there bringing Wingate. Two American war correspondents asked for a lift when he was leaving, and he took them despite the pilot’s protest that the plane was overloaded. It crashed in the jungle killing all aboard.

To the north-east Galahad Force, exhausted, sick and under-nourished, struggled on in appalling conditions towards Myitkyina. Monsoon rains, leeches, lice and the usual jungle diseases, especially malaria–and even cerebral malaria–took their toll. So too did sepsis, pneumonia and meningitis. The dead were buried but jackals soon dug up their bodies. Resupplying Merrill’s men by air was almost impossible in a terrain of deep valleys with impenetrable bamboo thickets and elephant grass, as well as the steep ridges in the Kumon Mountains which rose to 1,800 metres.

The Chindits were also exhausted and famished, and many fell sick, but this time providing they were close to an airstrip they could be evacuated by light aircraft along with the wounded, rather than abandoned as on the earlier foray. Those too badly hurt to be moved were finished off with ‘

a lethal dose of morphine

’ or a revolver shot so that they would not fall alive into Japanese hands.

Almost everyone was emaciated after living on K-Rations, which simply did not provide sufficient calories. The exhaustion and strain was such that there were many psychological casualties towards the end. ‘

You could see people

going downhill,’ observed the chief medical officer of the 111th Brigade. ‘Some even died in their sleep. The Gurkhas were the most resilient in our brigade. The Gurkha has a very tough upbringing in Nepal, and is used to hardship and disaster.’

Stilwell had little idea of what the Chindits were up to and how much they had achieved by cutting off Myitkyina from the south and west. The liaison between Stilwell and the British was almost non-existent and led to even greater ill-feeling. The obsessively anglophobic Stilwell, in the words of one observer, seemed to be ‘

fighting the War of Independence all over again

’.

While Stilwell’s forces struggled towards Myitkyina, the decisive battles of the war in Burma were taking place to the north-west. General Mutagachi’s ambitions for the 15th Army knew no bounds. He was encouraged by Subhas Chandra Bose to believe that with the so-called Indian National Army, recruited from prisoners of war in Japanese camps, the British Raj could be overthrown easily in a ‘March on Delhi’. But Mutagachi severely

underestimated the logistical problems which his offensive with three divisions would face.

He based his plan on first seizing the well-stocked British base at Imphal and making use of what he called ‘Churchill supplies’. After defeating the Indian division at Imphal, he intended to cut the Bengal–Assam railway line which supplied Stilwell’s Chinese divisions, and thus force them to retreat to their start-point of Ledo. Then he planned to destroy the airfields in Assam, which were used to support Slim’s Fourteenth Army and fly supplies over the Himalayas to China.

On 8 March, three days after the Chindits had landed well to their rear, Mutagachi’s 15th Army began to cross the River Chindwin. Slim told the headquarters of IV Corps to pull its divisions back to defensive positions on the Imphal Plain. Even though this withdrawal was demoralizing for his men, Slim saw that he needed to stretch the supply lines of the Japanese and shorten his own. Logistics would be the key to the battle in such terrain. Mountbatten also wasted no time. He commandeered US transport planes to fly in the 5th Indian Division as reinforcements, and sought permission from the combined chiefs of staff in Washington afterwards.

What the British command had failed to see was that a far stronger Japanese force than they had imagined was threatening Kohima eighty kilometres to the north of Imphal. This would cut off IV Corps and threaten the other supply base and airfield at Dimapur. The Japanese 31st Division had advanced rapidly from the Chindwin north towards Kohima, using mainly jungle trails. The British, not expecting them to move without motor transport, were taken by surprise. But the 50th Indian Parachute Brigade held them up in a magnificent week-long struggle around Sangshak.