The Second World War (12 page)

The French were determined not to share the fate of Poland. Yet most of their leaders and the bulk of the population had totally failed to recognize that this war would not be like earlier conflicts. The Nazis would never be satisfied with reparations and the surrender of a province or two. They intended to reorder Europe in their own brutal image.

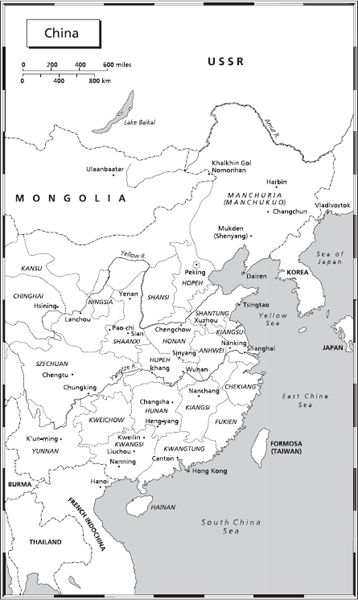

1937–1940

S

uffering was not a new experience for the impoverished mass of Chinese peasantry. They knew all too well the starvation which followed flood, drought, deforestation, soil erosion and the depredations of warlord armies. They lived in crumbling mud houses and their lives were handicapped by disease, ignorance, superstition and the exploitation of landowners who exacted between a half and two-thirds of their crop in rent.

City dwellers, including even many left-wing intellectuals, tended to see the rural masses as little more than faceless beasts of burden. ‘

Sympathy with the people

is utterly useless,’ a Communist interpreter said to the intrepid American journalist and activist Agnes Smedley. ‘There are too many of them.’ Smedley herself compared their lives to those of ‘peasant serfs of the Middle Ages’. They existed off tiny portions of rice, millet or squash, cooked in an iron cauldron, their most valuable possession. Many went barefoot even in winter and wore reed hats when working in the summer, bent over in the fields. Life was short, so old peasant women, wrinkled with age and hobbling still on bound feet, were comparatively rare. Many had never seen a motorcar or an aeroplane or even electric lighting. In much of the countryside warlords and landlords still ruled with feudal powers.

Life in the cities was no better for the poor, even for those with jobs. ‘

In Shanghai

,’ wrote an American journalist out there, ‘collecting the lifeless bodies of child labourers at factory gates in the morning is a routine affair.’ The poor were also oppressed by greedy tax-collectors and bureaucrats. In Harbin, the traditional beggar cry was ‘

Give! Give

! May you become rich! May you become an official!’ Sometimes the cry changed to: ‘May you become rich! May you become a general!’ Their fatalism was so inherent that real social change was beyond imagination. The revolution of 1911 which had marked the collapse of the Qing dynasty and brought in Dr Sun Yat-sen’s republic was middle class and urban. So at first was Chinese nationalism, aroused by the flagrant designs of Japan to exploit the country’s weakness.

Wang Ching-wei, who briefly became leader of the Kuomintang after the death of Sun Yat-sen in 1924, was the chief rival of the rising general Chiang Kai-shek. Chiang, proud and slightly paranoid, was deeply

ambitious and determined to become the great Chinese leader. A slim, bald man with a neat little military moustache, he was a highly skilled political operator, but he was not always a good commander-in-chief. He had been commandant of the Whampoa Military Academy and his favoured students were appointed to key commands. Yet because of rivalries and factional infighting within the National Revolutionary Army and between allied warlords, Chiang tried to control his formations from afar, often provoking confusion and delay as a result.

In 1932, the year after the Mukden Incident and the Japanese seizure of Manchuria, the Japanese moved marine detachments into their concession in Shanghai with conspicuous belligerence. Chiang foresaw a far worse onslaught to come and began to prepare. General Hans von Seeckt, the former commander-in-chief of the Reichswehr during the Weimar Republic, who arrived in May 1933, advised on how to modernize and professionalize the Nationalist armies. Seeckt and his successor, General Alexander von Falkenhausen, advocated a drawn-out war of attrition as the only hope against the better-trained Imperial Japanese Army. With little foreign exchange available, Chiang decided to trade Chinese tungsten for German weapons.

Chiang Kai-shek was a tireless modernizer and at this time inspired by genuine idealism. During what was known as the Nanking decade (1928– 37), he presided over a rapid programme of industrialization, roadbuilding, military modernization and improvements to agriculture. He also sought to end the psychological and diplomatic isolation of China. Yet, being well aware of China’s military weakness, he was determined to avoid a war with Japan for as long as possible.

In 1935, Stalin, through the Comintern, instructed the Chinese Communists to create a common front with the Nationalists against the Japanese threat. It was a policy which Mao Tse-tung in particular hardly welcomed after Chiang’s attacks on Communist forces which had forced him to embark in October 1934 on the Long March to avoid the destruction of his Red Army. In fact Mao, a large man with a curiously high-pitched voice, was viewed as a dissident by the Kremlin, because he saw that the interests of Stalin and those of the Chinese Communist Party were not the same. He believed along Leninist lines that war prepared the ground for a revolutionary seizure of power.

Moscow, on the other hand, did not want a war in the Far East. The interests of the Soviet Union were seen as far more important than a long-term victory for the Chinese Communists. The Comintern therefore accused Mao of lacking an ‘internationalist perspective’. And Mao came close to heresy by arguing that Marxist-Leninist principles of the primacy of the urban proletariat were unsuitable in China, where the peasantry

must form the vanguard of the revolution. He advocated independent guerrilla warfare, and the development of networks behind the Japanese lines.

Chiang sent representatives to meet the Communists. He wanted them to incorporate their forces within the Kuomintang army. In return they would have their own region in the north and he would cease attacking them. Mao suspected that Chiang’s policy was to push them into an area where they would be destroyed by the Japanese attacking from Manchuria. Chiang, however, knew that the Communists would never compromise or work with any other party in the long term. Their only interest was in achieving total power for themselves. ‘

The Communists are a

disease of the heart,’ he once said. ‘The Japanese a disease of the skin.’

While trying to deal with the Communists in southern and central China, Chiang could do little to stem Japanese incursions and provocations in the north-east. The Kwantung Army of Manchukuo argued with Tokyo, claiming that this was no time to compromise with China. Its chief of staff, Lieutenant General T j

j Hideki, the future prime minister, stated that preparing for war with the Soviet Union without destroying the

Hideki, the future prime minister, stated that preparing for war with the Soviet Union without destroying the

‘menace to our rear

’ in the form of the Nanking government was ‘asking for trouble’.

At the same time, Chiang Kai-shek’s policy of caution toward Japanese aggression produced widespread popular anger and student demonstrations in the capital. In late 1936, Japanese forces advanced into Suiyuan province on the Mongolian border, intent on seizing the coal mines and iron-ore deposits in the region. Nationalist forces counter-attacked and forced them out. This strengthened Chiang’s position, and his conditions for a united front with the Communists became tougher. The Communists with the North-Western Alliance of warlords, attacked Nationalist units in the rear. Chiang wanted to suppress the Communists completely while negotiations with them still continued. But at the beginning of December he flew to Sian for discussions with two Nationalist army commanders who wanted a strong line against Japan and an end to the civil war with the Communists. They seized him and detained him for two weeks until he agreed to their terms. The Communists demanded that Chiang Kai-shek should be arraigned before a people’s tribunal.

Chiang was released and returned to Nanking, having been forced to change his policy. There was genuine national rejoicing at the prospect of anti-Japanese unity. And on 16 December, Stalin, deeply alarmed by the Anti-Comintern Pact between Nazi Germany and Japan, put pressure on Mao and Chou En-lai, his subtle and more diplomatic colleague, to join a united front with the Nationalists. The Soviet leader feared that if the Chinese Communists made trouble in the north, then Chiang Kai-shek

might form an alliance with the Japanese against them. And if Chiang was removed, then Wang Ching-wei, who did not want to fight the Japanese, might take over leadership of the Kuomintang. Stalin encouraged the Nationalists to believe that he might well side with them in a war against Japan, purely to make sure that they resisted. And he continued to dangle that carrot without any intention of committing the Soviet Union to war.

An agreement between the Kuomintang and the Communists had still not been signed when the clash between Chinese and Japanese troops took place at the

Marco Polo

Bridge south-west of Peking on 7 July 1937. This incident marked the start of the main phase of the Sino-Japanese War. The whole incident was a black farce which demonstrates the terrifying unpredictability of events at a time of tension. A single Japanese soldier had become lost during a night exercise. His company commander demanded entry to the town of Wanping to search for him. When this was refused, he attacked it and the Chinese troops fought back, while the lost soldier found his own way back to barracks. An added irony was that the general staff in Tokyo were at last attempting to control their fanatical officers in China who were responsible for the provocations, while Chiang was now under strong pressure from his side not to compromise any more.

The generalissimo was uncertain about Japanese intentions and called a conference of Chinese leaders. At first, the Japanese military were themselves divided. Their Kwantung Army in Manchuria wanted to widen the conflict, while the general staff in Tokyo feared a reaction by the Red Army along the northern frontiers. There had been a clash on the Amur River just over a week before. Soon afterwards, however, the Japanese chiefs of staff decided on an all-out war. They believed that China could be knocked out rapidly before a wider conflict developed, either with the Soviet Union or with the western powers. Like Hitler with the Soviet Union later, Japanese generals made a grave error in grossly underestimating outrage among Chinese and their determination to resist. And it did not occur to them that China’s answering strategy would be to wage a drawn-out war of attrition.

Chiang Kai-shek, well aware of his own army’s deficiencies and the unpredictability of his allies in the north, knew the immense risks that war with Japan entailed. But he had little choice. The Japanese issued and repeated an ultimatum, which the Nanking government rejected, and on 26 July their army attacked. Peking fell three days later. Nationalist forces and their allies fell back, offering only sporadic resistance as the Japanese advanced southwards.

‘

Suddenly, the war

was upon us,’ wrote Agnes Smedley, who landed by junk on the north bank of the Yellow River at the ‘rambling mud town of Fenglingtohkow. This little town, in which we hoped to find lodgings

for the night, was a mass of soldiers, civilians, carts, mules, horses and street vendors. As we walked up the mud paths towards the town, we saw on either side long rows of wounded soldiers lying on the earth. There were hundreds of them swathed in dirty, bloody bandages, and some were unconscious… There were no doctors, nurses or attendants with them.’