The Second World War (31 page)

Hitler, however, had now begun to consider his own invasion of Greece, partly to end the Italian humiliation, which reflected badly on the Axis as a whole, but above all to protect Romania. On 12 November, he ordered the OKW to plan for an invasion through Bulgaria to secure the northern Aegean coastline. This was given the codename Operation Marita. The Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine soon persuaded him to include the whole of mainland Greece in the plan.

Marita would follow the completion of Operation Felix, the attack on Gibraltar in the spring of 1941, and the occupation of north-west Africa with two divisions. Fearing that the French colonies might defect from Vichy, Hitler ordered contingency planning for Operation Attila, the seizure of French possessions and the French fleet. These actions were to be carried out with great ruthlessness if opposed.

With Gibraltar as the key to the British presence in the Mediterranean, Hitler decided that he would send Admiral Canaris, the head of the Abwehr, to see Franco. He was to obtain agreement for the transit of German troops down Spain’s Mediterranean coastal road in February. But Hitler’s confidence that Franco would finally agree to enter the war on the Axis side proved over-optimistic. The Caudillo made it ‘

clearly understood

that he could enter the war only when Britain was facing immediate collapse’. Hitler was determined not to give up on this project, but, temporarily thwarted in the western Mediterranean, he focused his attention on Barbarossa’s southern flank.

On 5 December 1940, Hitler asserted that he intended to send only two Luftwaffe

Gruppen

to Sicily and southern Italy to attack British naval forces in the eastern Mediterranean. At that stage, he was against the idea of sending ground troops to support the Italians in Libya. But in the second week of January 1941 the devastating success of O’Connor’s advance prompted second thoughts. He cared little for Libya, but if Mussolini were overthrown as a consequence, it would represent a major blow to the Axis and give heart to his enemies.

The Luftwaffe’s presence in Sicily was increased to include the whole of X Fliegerkorps, and the 5th Light Division was ordered to prepare for North Africa. But by 3 February it became clear with O’Connor’s dramatic victory that Tripolitania was also at risk. Hitler ordered the despatch of a corps to be commanded by Generalleutnant Rommel, whom he knew well from the Poland campaign and France. The force was to be called the Deutsches Afrika Korps and the project given the codename Operation Sunflower.

Mussolini had no choice but to agree to Rommel being given effective command over Italian forces. After meetings in Rome on 10 February, Rommel flew to Tripoli two days later. He wasted no time in tearing up Italian plans for the defence of the city. The front would be held much further forward at Sirte until his troops had unloaded, but that, he soon discovered, would take time. The 5th Light Division would not be ready for action until early April.

In the meantime, X Fliegerkorps on Sicily pounded the island of Malta, especially airfields and the naval base of Valletta, and attacked British convoys running the Mediterranean gauntlet. The Kriegsmarine also tried to persuade the Italian navy to attack the British Mediterranean Fleet, but their arguments had little effect until the end of March.

Preparations for Operation Marita, the invasion of Greece, continued through the first three months of 1941. Formations of the Twelfth Army

under Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm List moved through Hungary into Romania. Both countries had anti-Communist regimes and had become Axis allies as a result of energetic diplomacy. Bulgaria also had to be won over so that German forces could cross its territory. Stalin watched these developments with deep suspicion. He was not convinced by the Germans’ assurances that their presence was aimed only against the British, but he could do little.

The British, all too aware of the German military build-up on the lower Danube, decided to act. Churchill, for reasons of British credibility and in the hope of impressing the Americans, ordered Wavell to abandon any thoughts of advancing into Tripolitania and to send three divisions to Greece instead. Metaxas had just died of throat cancer, and the new prime minister Alexandros Koryzis, faced with the reality of the German threat, was now ready to accept any help, however small. Neither a lugubrious Wavell nor Admiral Cunningham felt that this expeditionary force could hope to hold off the Germans, but since Churchill believed that British honour was at stake and Eden was utterly convinced that it was the right course, on 8 March they had to concede. In fact over half the 58,000-strong force sent to fulfil the British guarantee to Greece consisted of Australians and New Zealanders. They were the formations most readily at hand, but this was to produce a good deal of Antipodean resentment later.

The commander of the expeditionary force was General Sir Maitland Wilson, known as ‘Jumbo’ because of his enormous height and girth. Wilson had no illusions about the battle ahead. After an over-optimistic briefing by the British minister in Athens, Sir Michael Palairet, he was heard to say: ‘

Well, I don’t know about that

. I’ve already ordered my maps of the Peloponnese.’ This, the southernmost part of the Greek mainland, was where his troops would have to be taken off in the event of defeat. The Greek adventure was seen by senior officers as likely to be ‘another Norway’. More junior Australian and New Zealand officers, on the other hand, enthusiastically spread out maps of the Balkans to study invasion routes up through Yugoslavia towards Vienna.

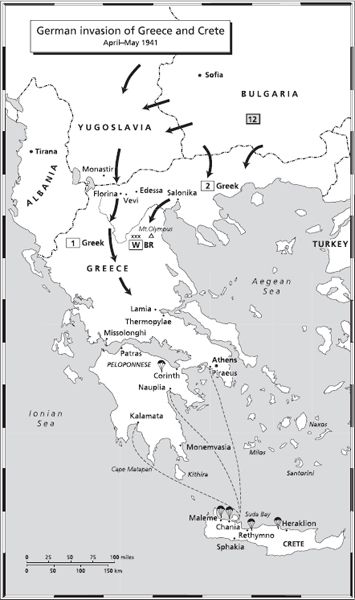

Wilson’s W Force prepared to face a German invasion from Bulgaria. It took up positions along the Aliakmon Line which ran partly along the river of that name and diagonally from the Yugoslav border down to the Aegean coast north of Mount Olympus. Major General Bernard Freyberg’s 2nd New Zealand Division was on the right and the 6th Australian Division on the left, with the British 1st Armoured Brigade out in front as a screen. The Allied troops remembered those days of waiting as idyllic. Although the nights were cold, the weather was glorious, wild flowers covered the mountains in profusion and Greek villagers could not have been more generous and welcoming.

While British and Dominion troops in Greece waited for the German attack, the Kriegsmarine put pressure on the Italian navy to attack the British fleet to divert attention away from the transports carrying Rommel’s troops to North Africa. The Italians would be supported by X Fliegerkorps in southern Italy and were encouraged to take revenge for the Royal Navy’s bombardment of Genoa.

On 26 March, the Italian navy put to sea with the battleship

Vittorio Veneto

, six heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and thirteen destroyers. Cunningham, warned of this threat through an Ultra intercept of Luftwaffe traffic, deployed available warships accordingly: his own Force A, with the battleships HMS

Warspite

,

Valiant

and

Barham

, the aircraft carrier HMS

Formidable

and nine destroyers; and Force B, with four light cruisers and four destroyers.

On 28 March, an Italian seaplane from the

Vittorio Veneto

sighted the cruisers of Force B. Admiral Angelo Iachino’s squadron set off in pursuit. He had no idea of Cunningham’s presence east of Crete and south of Cape Matapan. Torpedo aircraft from HMS

Formidable

hit the

Vittorio Veneto

, yet it managed to escape. A second wave damaged the heavy cruiser

Pola

, bringing it to a halt. Other Italian ships were ordered to help and this gave the British their chance. Devastating gunnery sank three heavy cruisers, inluding the

Pola

, and two destroyers. Although Cunningham was deeply frustrated by the escape of the

Vittorio Veneto

, the Battle of Cape Matapan represented a great psychological victory for the Royal Navy.

The German attack on Greece was planned to begin early in April, but an unexpected crisis exploded in Yugoslavia. Hitler had been trying to win over the country, and especially its regent, Prince Paul, as part of his diplomatic offensive to secure the Balkans before Operation Barbarossa. Yet resentment had been growing among the Yugoslavs, largely due to heavy-handed German attempts to obtain all their raw materials. Hitler urged the Belgrade government to join the Tripartite Pact, and on 4 March he and Ribbentrop put heavy pressure on Prince Paul.

The Yugoslav government delayed, well aware of growing opposition within the country, but the demands from Berlin became too insistent. Finally, Prince Paul and representatives of the government signed the pact on 25 March in Vienna. Two days later, Serbian officers seized power in Belgrade. Prince Paul was removed as regent and the young King Peter II placed on the throne. Anti-German demonstrations in Belgrade included an attack on the car of the German minister. Hitler, according to his interpreter, was left ‘

gasping for revenge

’. He became convinced that the British had a hand in the coup. Ribbentrop was immediately called out of a meeting with the Japanese foreign minister, to whom he had just suggested that

Japanese forces should seize Singapore. Hitler then ordered the OKH to prepare an invasion. There would be no ultimatum or declaration of war. The Luftwaffe was to attack Belgrade as soon as possible. The operation would be called Strafgericht–Retribution.

Hitler came to see the coup in Belgrade of 27 March as ‘

final proof

’ of the ‘conspiracy of the Jewish Anglo-Saxon warmongers and the Jewish men in power in the Moscow Bolshevik headquarters’. He even managed to convince himself that it was a vile betrayal of the German–Soviet friendship pact, which he had already planned to break.

Although the Yugoslav government had declared Belgrade an open city, Strafgericht went ahead on Palm Sunday, 6 April. Over two days, the Fourth Luftflotte destroyed most of the city. Civilian casualties are impossible to assess. Estimates vary between 1,500 dead and 30,000, with the probable figure roughly halfway between. The Yugoslav government hurriedly signed a pact with the Soviet Union, but Stalin did nothing because he was afraid of provoking Hitler.

While the bombing of Belgrade went ahead that Sunday morning with 500 aircraft, the German minister in Athens informed the Greek prime minister that Wehrmacht forces would invade Greece because of the presence of British troops on its soil. Koryzis answered that Greece would defend itself. Just before dawn on 6 April, List’s Twelfth Army began simultaneous offensives south into Greece and west into Yugoslavia. ‘

At 05.30 hours the attack

on Yugoslavia began,’ a Gefreiter in the 11th Panzer Division recorded in his diary. ‘The panzers started up. Light artillery opened fire, heavy artillery came into action. Reconnaissance aircraft appeared, then 40 Stukas bombed the positions, the barracks caught fire… a magnificent sight at daybreak.’

Early the same morning, the famously arrogant General der Flieger Wolfram von Richthofen, the commander of VIII Fliegerkorps, went to watch the attack of the 5th Mountain Division by the Rupel Pass near the Yugoslav border and see his Stukas in action. ‘

At the command post

at 04.00 hours,’ he wrote in his diary. ‘As it became light, the artillery began. Powerful fireworks. Then the bombs. The thought arises whether we are not paying the Greeks too much of a compliment.’ But the 5th Mountain Division received a nasty surprise and Richthofen’s aircraft bombed their own troops by mistake. The Greeks proved much more tenacious than he had expected.

The hastily mobilized Yugoslav army, lacking both anti-aircraft and anti-tank guns, did not stand a chance against the might of the Luftwaffe and German panzer divisions. The Germans noted that Serbian units resisted with rather more determination than Croats or Macedo nians, who often surrendered at the first opportunity. One column of 1,500

prisoners was attacked in error by Stukas, killing a ‘horrifying number’ of them. ‘

That’s war

!’ was Richthofen’s reaction.

The invasion of Yugoslavia created an unexpected danger to the Aliakmon Line. If the Germans came south through the Monastir Gap near Florina, as surely they would, then the Allied positions would be outflanked immediately. The troops on the Aliakmon Line had to be pulled back to meet this threat.

Hitler wanted to cut off the Allied expeditionary force in Greece and destroy it. He did not know that General Wilson had a secret advantage. For the first time, Ultra intercepts decoded at Bletchley Park were able to provide a commander in the field with warnings of Wehrmacht moves. But both the British and Greek commands were dismayed by the rapid collapse of the Yugoslav army, which killed only 151 Germans in the whole campaign.

Greek forces defending the Metaxas Line up near the Bulgarian border fought with great bravery, but eventually part of the German XVIII Mountain Corps broke through via the south-eastern extremity of Yugoslavia and opened the route to Salonika. On the morning of 9 April, Richthofen heard the ‘

astonishing news

’ that the 2nd Panzer Division had entered its suburbs. Yet the Greeks continued to mount counter-attacks near the Rupel Pass, which forced a now more respectful Richthofen to divert bombers to break them up.