The Second World War (45 page)

On 3 October rumours of the rapid advance reached Orel, but the senior officers in the city refused to believe the reports and carried on drinking. Dismayed by this fatal complacency, Grossman and his companions set off on the road to Briansk, expecting to see German tanks at any moment. But they were just ahead. Guderian’s spearhead entered Orel at 18.00 hours, the leading panzers passing tramcars in the street.

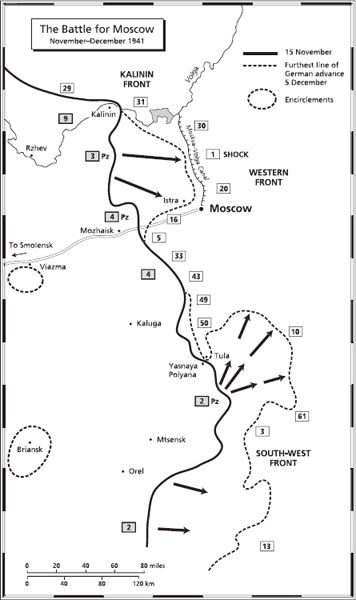

The day before, 2 October, the main phase of Typhoon had begun further north. After a short bombardment and the laying of a smokescreen, Third Panzer Group and Fourth Panzer Group smashed through on either side of the Reserve Front commanded by Marshal Budenny. Budenny, another cavalry crony of Stalin’s from the civil war, was a moustachioed buffoon and drunkard who could not find his own headquarters. Konev’s chief of staff was put in charge of launching the Western Front’s counter-attack with three divisions and two tank brigades, but they were brushed aside. Communications collapsed, and within six days the two panzer groups had surrounded five of Budenny’s armies, linking up at Viazma.

German tanks chased Red Army soldiers

, trying to crush them under their tracks. It became a form of sport.

The Kremlin had little information about the chaotic disaster taking place to the west. Only on 5 October did the Stavka receive a report from a fighter pilot who had sighted a twenty-kilometre column of

German armoured vehicles advancing on Yukhnov. No one dared believe it. Another two reconnaissance flights were sent out, both of which confirmed the sighting, yet Beria still threatened to put their commander in front of an NKVD tribunal as a ‘

panic-monger

’. Stalin, nevertheless, recognized the danger. He summoned a meeting of the State Defence Committee and sent Zhukov in Leningrad a signal telling him to return to Moscow.

Zhukov arrived on 7 October. He claimed later that when he entered Stalin’s room he overheard him telling Beria to use his agents to make contact with the Germans about the possibility of making peace. Stalin ordered Zhukov to go straight to Western Front headquarters and report back on the exact situation. He arrived after nightfall to find Konev and his staff officers bent over a map by candlelight. Zhukov had to telephone Stalin to tell him that the Germans had encircled five of Budenny’s armies west of Viazma. In the early hours of 8 October, he discovered at Reserve Front headquarters that Budenny had not been seen for two days.

The conditions within the encirclements at Viazma and Briansk were indescribable. Stukas, fighters and bombers attacked any groups large enough to merit their attention, while the surrounding panzers and artillery fired constantly at the trapped forces. Rotting bodies piled up, filthy and starving Red Army soldiers slaughtered horses to eat, while the wounded died untended in the chaos. Altogether, nearly three-quarters of a million men had been cut off. Those who surrendered were ordered to throw away their weapons and march westwards without food. ‘

The Russians are beasts

,’ wrote a German major. ‘They are reminiscent of the brutalized expressions of the Negroes in the French campaign. What a rabble.’

When Grossman escaped from Orel on 3 October just ahead of the Germans, he had been heading for Yeremenko’s headquarters in the forest of Briansk. Throughout the night of 5 October, Yeremenko waited for an answer to his request to withdraw, but no authorization came from Stalin. In the early hours of 6 October, Grossman and the correspondents with him were told that even front headquarters was now threatened. They had to drive as fast as possible towards Tula before the Germans cut the road. Yeremenko was wounded in the leg and nearly captured during the encirclement of the Briansk Front. Evacuated by aeroplane, he was more fortunate than Major General Mikhail Petrov, the commander of the 50th Army, who died of gangrene in a woodcutter’s hut deep in the forest.

Grossman was dismayed by the chaos and fear behind the lines. In Belev on the road to Tula, he noted: ‘

Lots of mad rumours

are circulating, ridiculous and utterly panic-stricken. Suddenly, there is a mad storm of firing. It turns out that someone has switched on the street lights, and soldiers

and officers opened rifle and pistol fire at the lamps to put them out. If only they had fired like this at the Germans.’

Not all Soviet formations were fighting badly, however. On 6 October the 1st Guards Rifle Corps, commanded by Major General D. D. Lelyushenko, supported by two airborne brigades and Colonel M. I. Katukov’s 4th Tank Brigade, counter-attacked Guderian’s 4th Panzer Division near Mtsensk in a clever ambush. Katukov concealed his T-34s in the forest, allowing the leading panzer regiment to pass by. Then, when they were halted by Lelyushenko’s infantry, his tanks emerged from the trees and attacked. Handled well, the T-34 was superior to the Mark IV panzer, and the 4th Panzer Division suffered heavy losses. Guderian was clearly shaken to discover that the Red Army was starting to learn from its mistakes and from German tactics.

That night it snowed, then thawed rapidly. The

rasputitsa

, the season of rain and mud, had arrived just in time to slow the German advance. ‘

I don’t think anyone

has seen such terrible mud,’ Grossman noted. ‘There’s rain, snow, hailstones, a liquid, bottomless swamp, black pastry mixed by thousands and thousands of boots, wheels and caterpillar tracks. And everyone is happy once again. The Germans must get stuck in our hellish autumn.’ But the advance, although slowed, carried on towards Moscow.

On the Orel–Tula road, Grossman could not resist visiting the Tolstoy estate at Yasnaya Polyana. There he found Tolstoy’s granddaughter packing up the house and museum to evacuate it before the Germans arrived. He immediately thought of the passage in

War and Peace

when old Prince Bolkonsky had to leave his house of Lysye Gory as Napoleon’s army approached. ‘

Tolstoy’s grave

,’ he jotted in his notebook. ‘Roar of fighters over it, humming of explosions and the majestic autumn calm. It is so hard. I have seldom felt such pain.’ The next visitor after their departure was General Guderian, who was to make the place his headquarters for the advance on Moscow.

Only a few Soviet divisions escaped from the Viazma encirclement to the north. The smaller Briansk pocket was proving to be the greatest disaster so far, with more than 700,000 men dead or captured. The Germans scented victory and euphoria spead. The route to Moscow was barely defended. Soon the German press was claiming total victory, but this made even the ambitious Generalfeldmarschall von Bock feel uneasy.

On 10 October, Stalin ordered Zhukov to take over command of the Western Front from Konev and the remnants of the Reserve Front. Zhukov managed to persuade Stalin that Konev (who would later become his great rival) should be retained rather than made a scapegoat. Stalin told Zhukov to hold the line at Mozhaisk, just a hundred kilometres from

Moscow on the Smolensk highway. Sensing the scale of the disaster, the Kremlin ordered a new line of defence to be constructed by a quarter of a million civilians, mostly women, conscripted to dig trenches and anti-tank ditches. Numbers of them were killed by strafing German fighters as they worked.

Discipline became even more ferocious, with NKVD blocking groups ready to shoot anyone who retreated without orders. ‘

They used fear

to conquer fear,’ an NKVD officer explained. The NKVD Special Detachments (which in 1943 became SMERSh) were already interrogating officers and soldiers who had escaped from encirclements. Any classed as cowards or suspected of having had contact with the enemy were shot or sent to

shtrafroty –

punishment companies. There, the most deadly tasks awaited them, such as leading attacks through minefields. Criminals from the Gulag were also conscripted as

shtrafniks

, and criminals they remained. Even the

execution of a gang boss

by an NKVD man shooting him in the temple had only a temporary effect on his followers.

Other NKVD squads went to field hospitals to investigate possible cases of self-inflicted injuries. They immediately executed so-called ‘self-shooters’ or ‘left-handers’–those who shot themselves through the left hand in a naive attempt to escape fighting. A Polish surgeon with the Red Army later admitted to amputating the hands of boys who tried this, just to save them from a firing squad. Prisoners of the NKVD of course fared even worse. Beria had 157 prominent captives executed, including Trotsky’s sister. Others were dealt with by guards throwing hand-grenades into their cells. Only at the end of the month, when Stalin told Beria that his conspiracy theories were ‘

rubbish

’, did the ‘mincing machine’ slacken.

The deportation of 375,000 Volga Germans to Siberia and Kazakhstan, which had begun in September, was accelerated to include all those of German origin in Moscow. Preparations to blow up the metro and key buildings in the capital began. Even Stalin’s dacha was mined. NKVD assassination and sabotage squads moved to safe houses in the city, ready to carry out guerrilla warfare against a German occupation. The diplomatic corps received instructions to depart for Kuibyshev on the Volga, a city which had already been earmarked as a reserve capital for the government. The main theatre companies in Moscow, symbols of Soviet culture, were also told to evacuate the capital. Stalin himself could not make up his mind whether to stay or leave the Kremlin.

On 14 October, while part of Guderian’s Second Panzer Army in the south circumvented the fiercely defended city of Tula, the 1st Panzer Division captured Kalinin north of Moscow, seizing the bridge over the upper Volga and severing the Moscow–Leningrad railway line. In the centre, the SS

Das Reich

Division and the 10th Panzer Division arrived at the

Napoleonic battlefield of Borodino, just 110 kilometres from the capital. Here they faced a hard fight against a force strengthened by the new Katyusha rocket launchers and two Siberian rifle regiments, forerunners of many divisions whose deployment round Moscow would take the Germans by surprise.

Richard Sorge, the key Soviet agent in Tokyo, had discovered that the Japanese were planning to strike south into the Pacific against the Americans. Stalin did not trust Sorge entirely, even though he had been right about Barbarossa, but the information was confirmed by signals intercepts. The reduced threat to the far east of the Soviet Union allowed Stalin to start bringing even more divisions westwards along the Trans-Siberian Railway. Zhukov’s victory at Khalkhin Gol had played an important part in this major strategic shift by the Japanese.

The Germans had underestimated the effect on their advance of the rain and snow, turning routes into quagmires of thick, black mud. Supplies of fuel, ammunition and rations could not get through, and the advance slowed. It was also delayed by the resistance of soldiers still trapped in the encirclement, preventing the invaders from releasing troops to continue the advance on Moscow. General der Flieger Wolfram von Richthofen flew at low altitude over the remains of the Viazma pocket, and noted the piles of corpses and the destroyed vehicles and guns.

The Red Army was also helped by interference from Hitler. The 1st Panzer Division at Kalinin, poised to attack south towards Moscow, was suddenly told to move in the opposite direction with the Ninth Army to attempt another encirclement with Army Group North. Hitler and the OKW had no idea of the conditions in which their troops were fighting, but

Siegeseuphorie

, or victory euphoria in Führer headquarters, was dissipating the concentration of forces against Moscow.

Stalin and the State Defence Committee decided on 15 October to evacuate the government to Kuibyshev. Officials were told to leave their desks and climb into lines of trucks outside which would take them to the Kazan Railway Station. Others had the same idea. ‘

Bosses from many factories

put their families on trucks and got out of the capital and that is when it started. Civilians started looting the shops. Walking along the street, one saw everywhere the red, contented drunken faces of people carrying rings of sausage and rolls of fabric under their arm. Things were happening which would be unthinkable even two days ago. One heard in the street that Stalin and the government had fled Moscow.’

The panic and looting were spurred on by wild rumours that the Germans were already at the gates. Frightened functionaries destroyed their Communist Party cards, an act many of them were to regret later once

the NKVD restored order, because they would be accused of criminal defeatism. On the morning of 16 October, Aleksei Kosygin entered the building of Sovnarkom, the Council of People’s Commissars, of which he was deputy chairman. He found the place unlocked and abandoned, with secret papers on the floor. Telephones rang in empty offices. Guessing that they were calls from people trying to discover whether the government had left, he answered one. An official asked whether Moscow would be surrendered.

Out in the streets, the police had vanished. As in western Europe the year before, Moscow suffered from enemy-paratrooper psychosis. Natalya Gesse, hobbling on crutches after an operation, found herself ‘

surrounded by mobs

suspicious that I had broken my legs parachuting in from a plane’. Many of the looters were drunk, justifying their actions on the grounds that they had best take what they could before the Germans seized it. Panic-stricken crowds at stations trying to storm departing trains were described as ‘

human whirlpools

’ in which children were torn from their mothers’ arms. ‘

What went on at Kazan

station defies description,’ wrote Ilya Ehrenburg. Things were little better at the western train stations of Moscow, where hundreds of wounded soldiers had been dumped, uncared for, on stretchers along the platforms. Women searching desperately for a son, a husband or a boyfriend moved among them.