The Second World War (71 page)

Ilya Ehrenburg was one of the few writers to visit the fighting there.

‘

One part of a small wood

on the outskirts of [Rzhev] had been a battlefield; the trees blasted by shells and mines looked like stakes driven in at random. The earth was criss-crossed by trenches; dugouts bulged like blisters. One shell-hole gaped into the next… The deep roar of guns and the furious bark of mortars were deafening, then suddenly, during a lull of two or three minutes, the chatter of machineguns would heard… In the field hospitals they were giving blood-transfusions, amputating arms and legs.’ The Red Army had suffered 70, 374 dead and 145,300 wounded, a massive sacrificial tragedy that was kept secret for nearly sixty years.

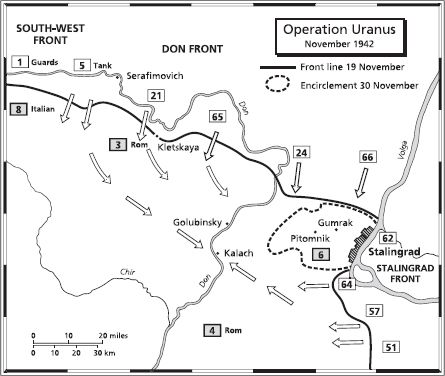

For the great encirclement operation against the Sixth Army, Zhukov reconnoitred in person the attack sectors on the Don while Vasilevsky visited the armies south of Stalingrad. There, Vasilevsky ordered a limited advance to just beyond the line of salt lakes to provide a better start-line. Secrecy was of paramount importance. Even the army commanders were not told of the plan. Civilians were evacuated from behind the front. Their villages would be needed to conceal the troops being brought up at night. Soviet camouflage was good, but not good enough to hide the assembly of so many formations. Yet this was not critical. While Sixth Army and Army

Group B staff officers expected some sort of attack on the Romanian-held sector to the north-west to cut the railway line to Stalingrad, they never imagined an attempt at outright encirclement. The ineffective attacks on their northern flank near Stalingrad had convinced them that the Red Army was incapable of launching a deadly strike. All Hitler was prepared to do was to allocate the very weak XLVIII Panzer Corps as a reserve behind the Romanian Third Army. It consisted of the 1st Romanian Armoured Division with obsolete tanks, the 14th Panzer Division which had been ground down in the fighting for Stalingrad, and the 22nd Panzer Division whose vehicles had been immobile for so long due to lack of fuel that mice, escaping the cold, hid inside them and gnawed through the wiring.

As a result of transport shortages, Operation Uranus had to be postponed until 19 November. Stalin’s patience was severely taxed. With more than a million men now in position, he was terrified that the Germans would discover what was happening. From north of the Don the 5th Tank Army, the 4th Tank Corps, two cavalry corps and other rifle divisions crossed at night into the bridgeheads. South of Stalingrad, two mechanized corps, a cavalry corps and supporting formations were brought across the Volga in the dark, a perilous undertaking with the ice floes coming down the river.

During the night of 18–19 November, Soviet sappers in the Don bridgeheads had crawled forward through the snow in white camouflage uniforms to clear minefields. In the thick, freezing mist they were invisible to the Romanian sentries. At 07.30 hours, Moscow time, howitzers, artillery, mortars and Katyusha rocket regiments all opened fire simultaneously. Despite the bombardment, which made the ground tremble fifty kilometres away, the Romanian soldiers resisted far more tenaciously than German liaison officers had expected. As soon as the tanks were thrown into the attack, steamrolling the barbed wire, the Soviet advance began, with T-34s and cavalry cantering across the snowfields. Caught in the open, German infantry divisions found themselves fighting off cavalry charges ‘

as if it were 1870

’, as one officer wrote.

Sixth Army headquarters was not unduly alarmed, and it heard that the XLVIII Panzer Corps was advancing to counter the breakthrough. But interference from Führer headquarters and changes of orders caused confusion. With 22nd Panzer Division barely able to move because most of its tanks’ electrics were still unrepaired, Generalleutnant Ferdinand Heim’s counter-attack collapsed in chaos. When Hitler found out, he wanted Heim shot.

By the time Paulus started to react it was far too late. His infantry divisions lacked their horses and thus their mobility. His panzer formations were still tied down in Stalingrad itself, and unable to disengage quickly

because of attacks launched by General Chuikov to prevent this. When they were finally free, the panzer troops were ordered west to join Generalleutnant Karl Strecker’s XI Corps to block the breakthrough far in their rear. But this meant that the southern flank, guarded by the Fourth Romanian Army, was left with just the 29th Motorized Division as a reserve.

On 20 November, General Yeremenko gave the order for the southern attack to begin. Led by two mechanized corps and a cavalry corps, the 64th, 57th and 51st Armies began to advance. The moment of revenge had come, and morale was high. Wounded soldiers refused to be evacuated to the rear. ‘

I’m not leaving

,’ said a member of the 45th Rifle Division. ‘I want to attack with my comrades.’ Romanian soldiers surrendered in large numbers, and many were shot out of hand.

Without air reconnaissance at this crucial moment, Sixth Army headquarters failed to apprehend the Soviet plan. This was for the two thrusts to meet up in the area of Kalach on the Don, having encircled the whole of the Sixth Army. On the morning of 21 November, Paulus and his staff in their headquarters at Golubinsky, twenty kilometres north of Kalach, had little idea of the danger. But as the day progressed, with alarming reports arriving of the progress of the Soviet spearheads, they became aware of the imminent catastrophe. There were no units available to stop the enemy, and their own headquarters was now threatened. Files were burned rapidly, and disabled reconnaissance aircraft on the landing strip destroyed. That afternoon Führer headquarters signalled Hitler’s order: ‘

Sixth Army stand firm

in spite of danger of temporary encirclement.’ The fate of the largest formation in the whole Wehrmacht was about to be sealed. Kalach, with its bridge over the Don, was virtually undefended.

The commander of the Soviet 19th Tank Brigade discovered from a local woman that German tanks always approached the bridge with their lights on. He therefore put two captured panzers at the head of his column, ordered all drivers to turn on their lights, and drove straight on to the bridge at Kalach before the scratch unit of defenders and Luftwaffe anti-aircraft guncrews realized what was happening.

The next day, Sunday, 22 November, the two Soviet spearheads met up in the frozen steppe, guided towards each other by firing green flares. They embraced with bear-hugs, exchanging vodka and sausage to celebrate. For the Germans, that day happened to be

Totensonntag

–the day of remembrance for the dead. ‘

I don’t know how it is all

going to end,’ Generalleutnant Eccard Freiherr von Gablenz, the commander of the 384th Infantry Division, wrote to his wife. ‘This is very difficult for me because I should be trying to inspire my subordinates with an unshakeable belief in victory.’

OCTOBER–NOVEMBER 1942

I

n October 1942, while Zhukov and Vasilevsky were preparing their great encirclement of the Sixth Army at Stalingrad, Rommel was in Germany on sick leave. He had been suffering from stress, with low blood pressure and intestinal problems. His last attempt to break through the Eighth Army in the Battle of Alam Halfa had failed. Many of his troops were also ill, as well as desperately short of food, fuel and ammunition. After all his dreams of conquering Egypt and the Middle East had turned to ashes, Rommel refused to accept personal responsibility. He went on to convince himself that Generalfeldmarschall Kesselring had deliberately held back supplies for the Panzerarmee Afrika out of jealousy.

The Panzerarmee Afrika’s position was indeed serious. The Italians in the rear areas and the Luftwaffe were keeping the bulk of the supplies for themselves. German morale was very low. Thanks to Ultra intercepts, Allied submarine attacks and bombing sank even more freighters in October. Hitler’s distrust of his ‘anglophile allies’ convinced him ‘

that German transports

were being betrayed to the English by the Italians’. The possibility that German Enigma codes were being broken did not occur to him.

General der Panzertruppe Georg Stumme, the corps commander who had been court-martialled for the loss of the plans for Operation Blau, commanded the army in Rommel’s absence, and Generalleutnant Wilhelm von Thoma took over the Afrika Korps. Hitler and the OKW did not believe that the British would attack before the next spring, and therefore there was still a chance for the Panzerarmee Afrika to break through to the Nile Delta. Rommel and Stumme were more realistic. They knew that they could do little in the face of Allied air power and the Royal Navy’s attacks on their supply convoys.

Rommel was further dismayed by the complacency he encountered in Berlin when he received his field marshal’s baton. Göring dismissed Allied air power, saying: ‘

Americans can only make

razor blades.’ ‘Herr Reichsmarschall,’ Rommel replied, ‘I wish we had such razor blades.’ Hitler promised to send forty of the new Tiger tanks, together with units of Nebelwerfer multi-barrelled rocket launchers, as if these would be more than enough to make up for his shortages.

The OKW played down any suggestion that the Allies might land in

north-west Africa in the immediate future. Only the Italians took the threat seriously. They made contingency plans to occupy French Tunisia, a project which the Germans opposed for fear of resistance from the Vichy French forces. In fact, Allied planning for Operation Torch was more advanced than even the Italians suspected. In early September, Eisenhower’s headaches began to lessen as transatlantic disagreements were resolved. There would be simultaneous landings at Casablanca on the Atlantic coast, and at Oran and Algiers in the Mediterranean. But the supply problem, due to confusion and a shortage of shipping, became a nightmare for his chief of staff, Major General Walter Bedell Smith. Most of the troops crossing the Atlantic arrived without weapons or equipment, so amphibious training was delayed.

On the diplomatic front, both the American and British governments began to reassure Franco’s regime in Spain that they had no intention of violating Spanish sovereignty, either in North Africa or on the mainland. This was necessary to counter German rumours that the Allies planned to seize the Canary Islands. Fortunately, the pragmatic General Conde Francisco de Jordana was again foreign minister after Franco had removed his pro-Nazi and over-ambitious brother-in-law, Ramón Serrano Súñer. The diminutive and elderly Jordana was determined to keep Spain out of the war, and his appointment in September was a great relief to the Allies.

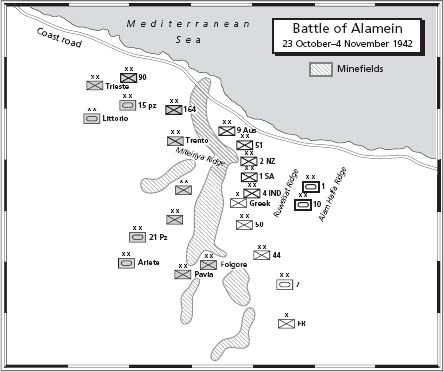

Stumme, although lacking precise intelligence, remained certain that Montgomery was preparing a major offensive. He stepped up patrol activity and accelerated the laying of nearly half a million mines, in so-called ‘devil’s gardens’ in front of the Panzerarmee Afrika’s positions. Following Rommel’s guidance, Stumme strengthened the Italian formations with German units and split the Afrika Korps, with the 15th Panzer Division behind the northern part of the front and the 21st Panzer Division in the south.

General Alexander acted as an umbrella, shielding Montgomery from Churchill’s impatience. Montgomery needed time to train his new forces, especially Lieutenant General Herbert Lumsden’s X Armoured Corps, which he proudly and over-optimistically called his

corps de chasse

. The newly arrived Shermans were being prepared, bringing the Eighth Army’s strength up to over a thousand tanks. Lumsden, a flamboyant cavalryman who had won the Grand National, was hardly Montgomery’s favourite but Alexander liked him.

Montgomery’s plan, Operation Lightfoot, consisted of making his main attack in the northern sector, which was also the most heavily defended. He assumed that the Germans would not expect this. Lumsden’s X Corps was to exploit the breakthrough once XXX Corps made it across the minefield south of the coast road. With the aid of a sophisticated deception plan

carried out by Major Jasper Maskelyne, a professional illusionist, Montgomery hoped to persuade the Germans that his main push was coming in the south, so that they would move their forces down there. Maskelyne installed hundreds of dummy vehicles and even a fake water pipeline in the southern sector. Radio traffic was stepped up in the area, transmitting pre-recorded signals, while trucks drove around towing chains behind the lines to stir up dust. To lend weight to this vital part of Montgomery’s plan, Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks’s XIII Corps would attack, followed by the 7th Armoured Division and supported by a third of his artillery. On the extreme left of the Alamein Line, Koenig’s Free French would attack the strong Italian position of Qaaret el Himeimat on the edge of the Qattara Depression, but they lacked sufficient support for such a difficult objective.