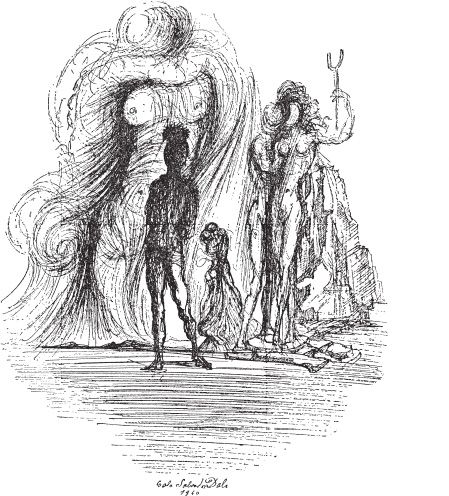

The Secret Life of Salvador Dali (50 page)

Read The Secret Life of Salvador Dali Online

Authors: Salvador Dali

Gala had in fact gathered together the mass of disorganized and unintelligible scribblings that I had made throughout the whole summer at Cadaques, and with her unflinching scrupulousness she had succeeded in giving these a “syntactic form” that was more or less communicable. These formed fairly well-developed notes which on Gala’s advice I took up again and recast into a theoretical and poetic work which was to appear under the title,

The Visible Woman

. It was my first book, and “the visible woman” was Gala. The ideas which were to be developed in this book were those for which I was soon to begin my battle in the very heart of the hostility and constant suspicion of the surrealist group itself.

Gala, moreover, had first of all to win her own battle in order that the ideas I expressed in my work could be taken half-way seriously even if only by the group of friends most prepared to admire me. As we shall see in the beginning of the third part of this book, a primordial fact, which everyone already unconsciously guessed, was that I had come to destroy their revolutionary work, using the same weapons, only much sharper and more formidable than theirs.

Already in 1929 I was in reaction against the “integral revolution” released by the post-war dilettante anxiety. And even while I hurled myself with greater violence than any of them into demential and subversive speculations just to see what the heart of revolutions in the making carried in its belly, with the half-conscious Machiavellism in my scepticism I was already preparing the structural bases of the next historic level–that of eternal tradition.

The surrealist group appeared to me the sole one offering me an adequate outlet for my activity. Its chief, Andre Breton, seemed to me irreplaceable in his role of visible chief. I was going to make a bid for power, and for this my influence had to remain occult, opportunistic, and paradoxical.

I took definite stock of my positions, of my strongholds, of my inadequacies and of the weaknesses and resources of my friends–for they were my friends. One maxim became axiomatic for my spirit: If you decide to wage a war for the total triumph of your individuality, you must begin by inexorably destroying those who have the greatest affinity with you. All alliance depersonalizes; everything that tends to the collective is your death; use the collective, therefore, as an experiment, after which strike hard, and remain alone!

I remained constantly with Gala, and my love made me generous and disdainful. But suddenly this whole ideological battle, already crowding my brain with the incessant movement of troops which my philosophy-inchief zealously sent forth to protect all the frontiers of my brain against aggression, appeared to me premature. And I, the most ambitious of all contemporary painters, decided to leave with Gala on a voyage of love two days before the opening of my first painting exhibit in Paris, the artistic capital of the world. Thus I did not even see how the paintings in this first exhibit of my work were hung, and I confess that during our voyage Gala and I were so much occupied by our two bodies that we hardly for a single moment thought about my exhibit, which I already looked upon as “ours.”

Our idyll had its setting in Barcelona, and then in Sitges, a little village close to the Catalonian capital, which offered us the desolation of its beaches attenuated by the sparkling Mediterranean winter sun. For a month I had not written a word to my parents, and a slight sense of guilt would assail me every morning. And so I said to Gala,

“This can’t last forever. You know that I must live alone!”

Gala left me at Figueras and continued her voyage to Paris.

In my father’s dining-room the storm broke–a storm created wholly by myself over the slightest of my father’s complaints. He was brokenhearted at the more and more lofty and inconsiderate way I had of treating my family. The question of money was brought up. I had in fact signed a two-year contract with the Goemans Gallery, but I could not manage to remember what the terms were, and in thinking it over more carefully, I could not even say whether the contract was for two or three years, or perhaps for one! My father begged me to try to find it. I said that I did not know where I had put it, and that I wanted to put off looking for it for three days, when I would be going to Cadaques, and that there I would have plenty of time to do it. I said also that I had spent all the money Geomans had advanced me. This bowled my family over

completely. I then began to rummage in my pockets, and pulled out a bank note here and another there, half torn and so crumpled and bedraggled that they were certainly not usable. Everything in the way of small change I had thrown into the garden of a square before the station, not to be burdened by it. In a few moments of ransacking my pockets 1 had managed to gather together three thousand francs, which were left over from my trip.

The following day Luis Bunuel arrived in Figueras, having just received an order from the Vicomte de Noailles to make a film exactly according to our two fancies. I learned also that the same Vicomte de Noailles had bought

Le Jeu Lugubre

, and that almost all the rest of the paintings of my exhibit had been sold at prices that ranged between six and twelve thousand francs.

I left for Cadaques dizzy with my success, and began the film

L’Age d’Or

(The Golden Age). My mind was already set on doing something that would translate all the violence of love, impregnated with the splendor of the creations of Catholic myths. Even at this period I was wonderstruck and dazzled and obsessed by the grandeur and the sumptuousness of Catholicism. I said to Bunuel,

“For this film I want a lot of archbishops, bones and monstrances. I want especially archbishops with their embroidered tiaras bathing amid the rocky cataclysms of Cape Creus.”

Bunuel, with his naïveté and his Aragonese stubbornness, deflected all this toward an elementary anti-clericalism. I had always to stop him and say,

“No, no! No comedy. I like all this business of the archbishops; in fact, I like it enormously. Let’s have a few blasphematory scenes, if you will, but it must be done with the utmost fanaticism to achieve the grandeur of a true and authentic sacrilege!”

Bunuel left, taking with him the notes on which we had collaborated. He was going to begin to get

L’Age d’Or

into production so that it could start simmering, and I would come later.

I thus remained all alone in the house in Cadaques. In the winter sun I would eat at one sitting three dozen sea-urchins with wine, or five or six chops fried on a fire of vinestalks. In the evening a fish soup and cod with tomato, or else a good big fried sea-perch with fennel. One noonday while I was opening an urchin I saw before me a white cat. He had something coming out of one eye which flashed like quicksilver in the sun at each of its movements. I stopped eating my urchin and approached the cat. The cat did not move; on the contrary it continued to look at me all the more intently. Then I saw what it was: the cat’s eye was completely pierced through with a large fishhook, the point of which emerged from one side of its dilated and blood-shot pupil. It was frightful to see, and especially to imagine the impossibility of extracting this fish-hook without emptying the eye itself. I threw rocks at it to rid myself of the sight that filled me with an unspeakable horror. But the following days

just at the moments of my greatest enjoyment

20

and when it was most intolerable–as with a piece of well-toasted bread I was getting ready to empty an urchin shell of its palpitating coral–the apparition of the white cat with its eye pierced through with the silvery hook stopped my gluttonous gesture in an attitude of anguished paralysis. I finally became convinced that this cat was an omen.

A few days later I received a letter from my father notifying me of my irrevocable banishment from the bosom of my family. I do not wish to unveil here the secret which was at the root of such a decision, for this secret concerns only my father and myself, and I have no intention of reopening a wound which kept us apart for six long years and made both of us suffer so greatly. When I received this letter, my first reaction was to cut off all my hair. But I did more than this–I had my head completely shaved. I went and buried the pile of my black hair in a hole I had dug on the beach for this purpose, and in which I interred at the same time the pile of empty shells of the urchins I had eaten at noon. Having done this I climbed up on a small hill from which one overlooks the whole

village of Cadaques, and there, sitting under the olive trees, I spent two long hours contemplating that panorama of my childhood, of my adolescence, and of my present.

The same evening I ordered a taxi which would fetch me the next day and take me to the frontier where I would board a train straight for Paris. I had a breakfast composed of sea-urchins, toast and a little very bitter red wine. While waiting for the taxi, which was late in coming, I observed the shadow of my profile that fell on a white-washed wall. I took a sea-urchin, placed it on my head, and stood at attention before my shadow–William Tell.

The road that goes from Cadaques and leads toward the mountain pass of Peni makes a series of twists and turns, from each of which the village of Cadaques can be seen, receding farther into the distance. One of these turns is the last from which one can still see Cadaques, which has become a tiny speck. The traveler who loves this village then in-voluntarily looks back, to cast upon it a last friendly glance of leave-taking filled with a sober and effusive promise of return. Never had I neglected to turn around for this last glance at Cadaques. But on this day, when the taxi came to the bend in the road, instead of turning my head I continued to look straight before me.

1

See footnote to page 209.

2

Just recently, in writing the preface to the catalogue of my last New York exhibit, which I signed with my pseudonym Jacinto Felipe, I felt that I needed, among other things, to have someone write a pamphlet on me bearing a title something like “Anti-Surrealist Dali.” For various reasons I needed this type of “passport,” for I am myself too much of a diplomat to be the first to pronounce such a judgment. The article was not long in appearing (the title was approximately the one I had chosen), and it appeared in a modest but attractive review edited by the young poet Charles Henri Ford.

3

Miro, I remember, told me the

marseillais

story of the owl. Someone had promised to bring his friend a parrot on his return from America. Back in Marseilles he suddenly realized that he had forgotten his promise. He caught an owl, painted it green and presented it to his friend. After some time the two friends met. The returned traveler slyly asked, “How is the parrot I gave you? Does he talk yet?” And the other answered, “Talk, no. But he thinks a great deal.”

4

The Comte de Lautréamont, whose real name was Isidore Ducasse (1846-1870). His

Chants de Maldoror

, a fantastic, poetic, and highly neurotic novel, has had an enormous influence on surrealism.—Translator’s Note.

5

A word in artists’ slang to refer to painters under contract with a dealer.

6

Popular song of Aragon of exemplary racial violence.

7

When a war breaks out, especially a civil war, it would be possible to foresee almost immediately which side will win and which side lose. Those who will win have an iron health from the beginning, and the others become more and more sick. The ones can eat anything, and they always have magnificent digestions. The others, on the other hand, become deaf or covered with boils, get elephantiasis, and in short are unable to benefit by anything they eat. A rigorously controlled statistical study along this line could not fail to be of the highest scientific interest.