The Secret Life of Uri Geller (19 page)

Read The Secret Life of Uri Geller Online

Authors: Jonathan Margolis

Tags: #The Secret Life of Uri Geller: Cia Masterspy?

This symbiosis between Uri and Shipi would later become a matter of fascination to sceptical investigators, who wrote (incorrectly) that Uri could

only

function when Shipi was with him. The story, still quoted as gospel, was born that Uri’s ‘psychic’ abilities only appeared at this camp, that Shipi introduced Uri to a book he had on magic, and that the two jointly cooked up the scam which was to become the Uri Geller stage act. Some researchers even claim to know which book it was – a magicians’ textbook, still available, called

Thirteen Steps to Mentalism

by Tony Corinda, which was published in England in 1958.

Uri being Uri, meanwhile, he was actually rather more interested in Shipi’s 19-year-old sister, a pretty, green-eyed, strawberry blonde hippy-type, with a touch of the Faye Dunaway about her. He first met Hanna Shtrang at a parents’ day, when the whole Shtrang family came over from Tel Aviv to see Shipi. Uri and Shipi demonstrated some of the psychic stuff they had been doing together in the camp, and Hanna was hooked, even though with her, the experiments did not work particularly well. For the next 24 years, Hanna would be Uri’s on-off girlfriend, then full-time lover and mother of his children; the couple married in Budapest in 1991.

What Uri learned from the experience at Alumin was the entertainment value of what he could do. He also realized that even if things had worked out in the army, he would have been too extrovert for the anonymity of the secret service. So he thought a lot about whether he could be a professional entertainer in his last few months back in the army, the rather pleasant period which he spent driving around villages, chasing up – with great success, he claims – deserters and people who had not registered for military service.

At weekends and on leave, he practised his psychic stuff for the Shtrang family and a widening circle of friends. Shipi, although still only a schoolboy worked on the same project – turning Uri’s abilities into a viable stage act. He even did his first paid appearance, at Shipi’s school, which worked well. Significantly, he found, perhaps counterintuitively, that although people were suspicious of him, they still paid to see his act, went away having enjoyed the novel idea of a conjuror who pretends to be a

real

magician, and were sometimes powerfully affected by what they saw. Controversy, Uri and Shipi rapidly learned quickly, was not a drawback; on the contrary, it was their act’s biggest asset.

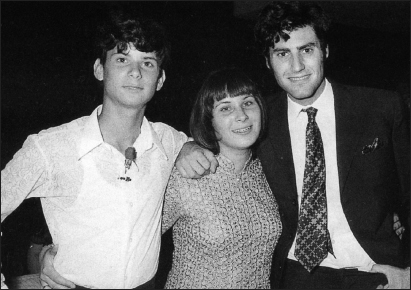

Shipi, Hanna and Uri, late 1960s, Tel Aviv, Israel.

After his service ended in November 1968, Uri, who had inherited his father’s dashing good looks, also did his spell as a model and made inroads, via the photographers, into Tel Aviv’s swinging, beautiful people scene. (His ads were less beautiful, something that can be testified to by anyone who has dug out studio shots for Kings Men underarm sticks, in which Uri is seen beaming as he applies deodorant to a hairy armpit, while being watched adoringly by some long-forgotten 60s’ beauty with long false eyelashes and her head level with Uri’s crotch.)

More importantly, Uri’s professional psychic career was taking shape. Shipi, still not 14, arranged for more shows in other schools, as well as demonstrations at private parties. Each one earned them no more than a few dollars, but for Uri, the increasing frequency of the appearances made him more and more confident that the powers he possessed could, within a reasonable margin of error, be summoned up on demand. And the strange, unprecedented kind of show the boys had put together was playing amazingly well with both up-market and down-market audiences. Was it a science project? Was it a magic show? Who cared? It was a unique event to have at your party.

Uri began seriously to think that capitalizing on his strange abilities could make him rich – rich enough, he dreamed, even to buy his mother a little coffee shop. He had already bought her a black-and-white Grundig TV set and himself a fancy hi-fi, and, always a big eater, indulged his appetite for food almost to the point of becoming as chubby as he had at times been as a child. He also bought a second- hand Triumph sports car and told Margaret that if she wanted to work, she was welcome to, but from now on, there was absolutely no need. Uri was perilously close to being famous. He appeared in the newspapers. Theories abounded in the press as to what this man Geller’s trick could be. Lasers, chemicals, accomplices in the audience and mirrors were all put forward as likely candidates. Fame, money, as much sex as he could handle with the pick of the Tel Aviv

belle monde

, and even a pretty, sensible girl waiting in the background to settle down with and have his babies. What more could a young man want?

Uri’s shows in Israel brought him an enthusiastic following. Seen here mending broken watches, brought to him by audience members.

His first fully professional stage show was in Eilat in December 1969, when he was approaching his 23rd birthday. Uri continued to insist that it was all ‘real’, but understandably, most people disbelieved him, assuming this was simply part of his patter. Importantly though, even the sceptics were fascinated by his act despite their belief that it was based on trickery. He was managing, he estimates, a success rate with the bending, telepathy and watch stopping and starting of 70 to 80 per cent. Who had ever heard of a magician, part of whose success was based on his tricks only working some of the time? Even the cynics had to admit, it was a devastatingly clever idea.

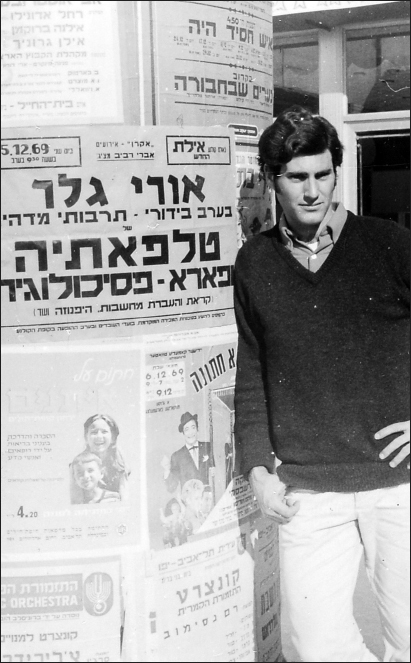

Uri next to poster for one of his very first shows: ‘An Evening of Amazing Cultural Entertainment of Telepathy and Parapsychology’, Eilat, 1969.

But the most significant development, even if Uri didn’t fully appreciate it at the time, was the interest in him from the country’s professional and military elite. One unlikely new friend he made at exclusive social gatherings was the dean of the law school at Tel Aviv University, Dr Amnon Rubinstein, who was an academic with a flair for the media. He wrote for a number of newspapers and hosted a popular TV show called

Boomerang

, which covered the arts, science and intellectual matters. Rubinstein was not only convinced by what he saw with Uri, but went on to become one of his great champions, writing articles about him widely and inviting him on to his show.

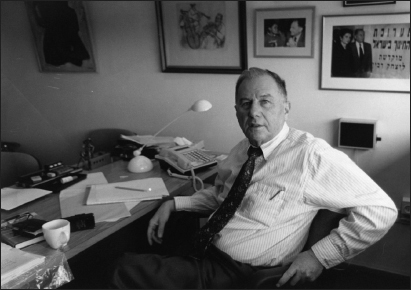

Rubinstein became a prominent left-wing member of the Knesset, eventually serving as Minister of Education in Yitzhak Rabin’s Labour government. He was introduced to Uri at a party by his friend Efraim Kishon, a respected newspaper columnist, who had been deeply impressed by what he had seen of Uri’s abilities. ‘Everyone was sceptical in the beginning, but these were amazing things we were seeing,’ Rubinstein recalls. He speaks with great passion about Geller.

Like a lot of older, more experienced, better educated and, perhaps, wiser and more intuitive people who have been in contact with Uri over the years, Rubinstein felt deeply that the explanations, often backed by angry scientists, that the ever more voluble professional magicians were putting forward to counter any claims that Uri had ‘special powers’ were fanciful and smacked more of emotion than rationality.

‘I had no specific interest in psychic things. I am a totally rational, sceptical person. So I am not a fall guy, but I am open-minded, and I saw things that I couldn’t explain. I first saw him at Kishon’s place and I immediately saw that there was something in it, that this was not mere conjuring,’ says Rubinstein. ‘He was not a trickster. I imagine the spoon bending is some sort of strange energy that we haven’t even begun to measure, but I suspect it’s subject to rational terms. I have since seen Uri do it hundreds of times. It has become almost routine. A magician told me that Uri supplies his own spoon, which is not true, but anyway, that wasn’t what interested me so much.

‘The thing that amazed me more than anything else is that he could write something ahead of time on a piece of paper and hide it, and would then tell me, my wife or my children or my friends to write whatever we wanted. It started with a very limited scope – any number, any name or any capital city – and without exception he was right. He could somehow plant a thought right in our minds. Then he moved on to drawings, and again, was right in detail, every time. To me this is much more significant than spoon bending. This was one single phenomenon, which cast doubt on many of the foundations of our rational world.

‘There are things which cannot be repeated by any trick. It’s one thing to be a David Copperfield, but here was something that was done in my own home, not in another environment, on a stage, which was organized and controlled as someone like that would require. There was nothing there that could deceive me, and it happened so often. We invited him time and time again. He came into my office once, and one of the professors came in and said, “You’re Uri Geller, but I know your tricks.” So Uri said, “OK. Think of a number,” and he said ‘Ten thousand three hundred and something,” and Uri opened up his palm and it was written there. My colleague was staggered.’

Amnon Rubinstein in 1998, then a prominent member of the Israeli parliament.

The power and vehemence of the reactions of the coalition of magicians and scientists against Geller were remarkable, considering that a year into his professional career, he was not a household name, but was fast becoming one. Even so, the man who would soon become his first serious manager, for example, Tel Aviv impresario Miki Peled, had as late as 1970 never heard of Uri Geller. Yet the word was getting round among Israeli magicians that a fraud was at large, claiming that he had paranormal powers. Spoon bending was a completely novel trick, but for skilled sleight-of-hand conjurors, replicating it was really no great feat. Uri’s supporters would say that replication by itself meant next to nothing – that just because there are wigs doesn’t mean there’s no hair. And it remains the case today, all these decades on – and something that still frustrates many magicians – that still nobody does it like Geller does.

Uri’s appearance on Rubinstein’s

Boomerang

programme, in accord with the show’s name, came back on him. In the interests of balance, Rubinstein had invited a number of voluble sceptics into the audience. Uri, assuming a civilized discussion would ensue, started the show only to find the anti-Geller people howling him down. ‘It was the first TV show I had ever done, and it would have been OK if they just didn’t believe me,’ Uri says. ‘But they were attacking me, really violently, with personal abuse. It was the first time I’d had direct, physical contact with these people, and I was really scared. Then I realized it was in my power just to walk off, so I did. Amnon followed me out of the building and he actually started crying, because he believed in me so much and it totally devastated him.’ The taped show was abandoned and never aired.