The Secret of Chanel No. 5 (5 page)

Read The Secret of Chanel No. 5 Online

Authors: Tilar J. Mazzeo

It was hard not to admire Poiret's business acumen. Although he would deny such suggestions strenuously and always claim that he had thrown the party only for the enjoyment of his special friends, it was in fact a brilliant way of introducing the arbiters of fashion to his new line of fragrances, Parfums de Rosine, which he had finished preparing for launch only days earlier. The line was named after his daughter, Rosine, and the first scents took their names from the theme of oriental harems, with fragrances like Nuit Persane (1911) and Le Minaret (1912). The bottles of that first scent were decorated using motifs drawn from the window decorations that were the signature of his well-known boutique, in case any of the ladies was liable to forget the connection between his scents and his salon.

In launching perfumes from his fashion house, Poiret became the first couturier in history to link design and fragrance. He had delighted all of Paris with his dramatic flair for marketing this novel perfume, and the newspapers were filled with descriptions of his extravagant partyâand of the new scents that could capture its spirit. Less than a decade later, in 1919, the obscure fashion designer Maurice Babani became the second couturier to launch a signature scent

7

. Coco Chanel would be the third. And, when the time came, she would remember the flair for which Poiret was everywhere celebrated.

For the moment, however, Coco Chanel set any fleeting thoughts of perfume aside. She threw herself instead into her romance with Boy Capel and into the introduction in 1913 of a simple line of sportswear in her boutique on the coast at Deauville, where the rich and fashionable people of France spent their leisure time. The next year, the First World War began, and the uniforms of the volunteer nurses of the era inspired her to create, in inexpensive jersey fabric, a line of simple, chic, and liberating dresses for the upper-class women who had been part of her circle since her first days at Royallieu. Within a few short years, these new fashions had made her name and made her a small fortune. By the time the war ended, Coco Chanel was already a famous designer.

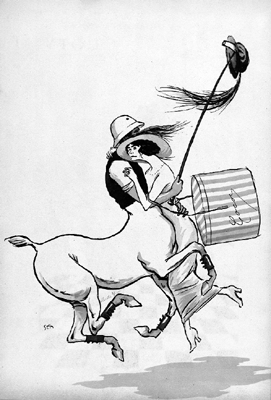

In fact, by 1914 she was even well enough known in high society to find her relationship with Boy Capel the target of gossip and public teasing. That year, the celebrity cartoonist and illustrator Georges Goursatâusually known simply by his signature “Sem"âpublished a sketch of her and Boy dancing at the fashionable resort town of Deauville sur Mer, titled simply “Tangoville sur Mer.” In it, the polo-mad Boy Capel is satirized as a lusty centaur running off with the dazed milliner, who, in case anyone missed the identification, carries a huge hatbox distinctly labeled “Coco.”

The caricature was a nod to the beginning of the tango craze that year in Europe, ignited by a bestselling book,

Modern Dancing,

written by the couple of the hour, Verne and Irene Castle

8

. Irene Castle was a scrappy socialite, an aspiring fashion designer, and, with her bobbed hair in 1914, alreadyâlike Coco Chanelâan early flapper, at a moment when the

garçonne

look was still shocking. The cartoon was also a pointed and rather mean-spirited dig at Boy's decadent equestrian indulgences and a sly allusion to the lusts of the mythological centaurs, known in Greek mythology for their habit of brashly abducting women. After all, just because he and Coco were in love didn't mean that Boy didn't have a stable of mistresses

9

. And everyone knew that Coco had been with Ãtienne before Boy Capel had charmed her.

Gabrielle Chanel and Arthur Capel by the cartoonist sem in 1913.

A caricature like this was not precisely the sort of coverage in the fashionable press a conflicted young

demi-rep

âas women who were only “half reputable” were calledâwould desire, but in a way it was a sign that she had arrived. Sketches like this, however, would also leave Coco Chanel wary of the press and determined to control her public image in ways that would profoundly shape some of her most critical decisions about businessâand one day the business of her Chanel No. 5 fragrance in particular.

During the next four years, the years of the First World War in Europe, Coco Chanel flourished. By the end of them, she could afford to treat herself to a seaside villa in the south of France and a “little blue Rolls

10

.” She was a celebrity, and she was quickly becoming rich as well. “The war helped me,” Chanel later remembered. “Catastrophes show what one really is. In 1919 I woke up famous.”

11

She had come a long way from the charity convent school of Aubazine and her days as a cabaret chanteuse.

She had done it by learning not to turn down lucky chances. When the war ended in November of 1918, though, there was one opportunity that Coco Chanel had missed completely: perfume. That winter in Paris, it would have been hard to miss. For months and months after the armistice, the city was still filled with many of the two million American soldiers

12

whose return home it would take the United States government the better part of a year to coordinate. While they waited, French fragrances were the souvenirs they all wanted. It was because of those soldiers that French perfumers became some of the wealthiest entrepreneurs in the world during that decade. Perfume was Paris. Paris was chic and sexy. The returning soldiers wanted something to show they had been there, something to help to remember it.

The story of the fantastic rise of French perfume during the early twentieth century is in many respects also an essentially American story, because had it not been for the American market and the American passion for Parisian fragrances, the fortunes made would have been far, far smaller. That market would one day be at the heart of the century's great passion for Coco Chanel's No. 5 perfume especiallyâa fragrance that went all but unadvertised in France for decades after its invention.

The interest in French perfume had been growing in the United States steadily even before the First World War, and large fragrance companies like Bourjois and Coty had begun setting up offices in the United States by the 1910s

13

. Now, these forward-thinking entrepreneurs were poised to become huge international successes with the frenzy for Parisian perfume that followed the armistice. No one had a story more amazing or more emblematic than the jaunty entrepreneur François Coty, who in 1919 became France's first billionaire. His wife Yvonne, who had also made her start as a fellow milliner in Paris

14

, was a friend of the stylish and already celebrated Coco Chanel.

If Paul Poiret and the fabulous success of his Parfums de Rosine first gave Coco Chanel the idea of linking a perfume line with a fashion house, it was François Coty who was now her real inspiration. Later, they would become rivals. Coty had the gift of an incredibly keen sense of smell and had stumbled upon perfumery one afternoon in the back room of a friend's pharmacy, where rows of scented materials were lined up in simple, medicinal bottles. He sold his first cologne from the back of a pony cart to women in the provinces, and now, at the end of the First World War, he was one of the world's most celebrated industrial magnates and a man of high culture. His perfumes were worn by czarinas at the Russian imperial court and by thousands of middle-class women elsewhere. In the burgeoning American market, Coty was quickly becoming a household name, and he was raking in a vast fortune. His story was one of a self-made entrepreneur finding fabulous success, and the enterprising young Coco Chanel, keen to make her fortune too, understood it intuitively.

So, sometime in late 1918 or perhaps early 1919, Coco Chanel threw herself into seriously planning the creation of her signature perfume. Of the many possible explanations for how Chanel No. 5 came into existence, perhaps the most intriguing is the legend that a long-lost secret perfume formula was the basis for Chanel's decision to produce a new fragrance in 1919. It is a story shrouded in mystery, and, were it not for evidence in the Chanel archives in Paris that affirm the formula's existence, it would be hard to take such a romantic tale seriously.

It was probably during the winter of 1918 that Coco Chanel received an excited visit from a friend, the bohemian socialite Misia Sert

15

, a woman whose great beauty was captured in paintings by Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec. Misia knew that Coco was researching the launch of a signature perfume. They had talked about it already, debated bottle designs, and even planned how Coco would market it to her couture clients

16

âor so Misia always claimed afterward. Now, Misia had heard of an amazing discovery in an old library in a château in the Loire valley. There, during renovations, the owners had discovered a Renaissance manuscript, and among its pages was a recipe. It was a formula for the lost “miraculous perfume” of the Medici queens

17

, an elixir said to preserve aging beauties from the ravages of time.

If authentic, both Misia and Coco Chanel knew that it would be an exciting discoveryâand a fabulous way to promote her fragrance among her wealthy clients. After all, the history of perfume-making in France began at the court of the Medici queens

18

, when the young Catherine de Medici was sent to France as the bride of King Henry II. Arriving from Italy, Catherine brought with her a certain Renato Bianco, better known simply as René the Florentine, as part of her entourage. René became the first official perfumer in French history, and, from his shop in sixteenth-century Paris, he supplied scented aphrodisiacal potions and fragrances for the art of seduction. When those went wrong and lovers strayed unaccountably, some said he also sold the occasional rare and deadly poison with which to dispatch the competitionâor the offender.

This perfume recipe, however, was said to belong to Catherine de Medici's cousin, Marie, who had also married into the French royal family and who was an even more committed perfume aficionado. In fact, it is because of Marie de Medici that the French village of Grasse, which started out as an artisan center for the production of gloves and leather tanning, became the fragrance capital of the world in the seventeenth century. As perfume historian Nigel Groom tells the story, she “set up a laboratory in Grasse for the study of perfume-making in order to rival the fashionable Arab perfumes

19

of the time, for which she is regarded by some as the founder of the French perfume industry.” The queen was obsessed with scents and aromaticsâand especially with their beauty secrets. Because she remained strikingly beautiful well into her sixties, no one doubted that she had found something magical.

Now, an ancient manuscript with one of Marie de Medici's perfumes had been discovered. Misia Sert urged Coco Chanel to buy it, and she did. She paid six thousand francsâthe equivalent of nearly $10,000 today

20

âfor the manuscript that revealed the secrets of this mysterious “cologne,” as light citrus-based scents were still fashionably called. Surely, Misia told her, it would be the perfect foundation for her signature beauty products. Coco Chanel must have agreed, because that summer she was apparently planning actively for its production. On July 24, 1919, company records show that Coco Chanel registered a trademark for a product line that she planned to call Eau ChanelâChanel water.

Misia Sert would later claim that this was the origin of Chanel No. 5

21

. She also claimed that she and Coco Chanel spent hours together designing the packaging and hitting upon the elegantly simple idea of using a common pharmaceutical bottle for the flacon. Perhaps if the turmoil in Coco Chanel's personal life had not intervened in the autumn of 1919, Chanel No. 5 would have been invented earlier. But nowhere in the Chanel archives is there any evidence that Coco Chanel got as far as ordering bottles that summer. The only evidence that hints at the production of any perfume is the report of a mysterious undated receipt said to have been discovered in the Coty company archives as late as the 1960s, which shows that her friend François billed Coco Chanel for some perfume laboratory work. His wife, Yvonne, always claimed that when Coco first began considering the idea of launching a fragrance, François offered to let her use his laboratory for the development.

22

Perhaps that summer Coco Chanel had moved forward with some preliminary formulations and this is behind the story of the bill in the Coty archives. Today, there is no way of knowing for sure. Chanel, however, believes that the story of any connection between the Coty laboratory and Chanel No. 5 is simply apocryphal. François's granddaughter, Elizabeth Coty, who tells the story in the biography of her famous relative, seems less certain. What is certain is that a perfume called Eau Chanel never existedâand, for reasons almost equally as complicated and circuitous, its scent could not possibly have been the inspiration behind Chanel No. 5.