The Seeds of Fiction (3 page)

Read The Seeds of Fiction Online

Authors: Bernard Diederich,Richard Greene

In the late summer of 1963 Greene decided he had better see the country again for himself. After a harrowing visit, he went on to the Dominican Republic for further briefing from Diederich, before writing his long article âThe Nightmare Republic' for the the

Sunday Telegraph

(22 September 1963). The story Diederich had been telling for six years was now given enormous attention, and while the new Johnson administration dithered world opinion shifted and Duvalier's Haiti became a pariah state.

It had been several years since Greene had written a novel â after the publication of A

Burnt-Out Case

in early 1961 Greene feared that he was near the end of his writing career. He wrote some short stories and an unsuccessful play, but Haiti now had a grip on him. In early 1965 Diederich took him on a tour of the border between Haiti and the Dominican Republic, including a memorable stop at the training camp of a tiny band of rebels in a disused lunatic asylum. For the first time in his life Greene wrote a novel with a political objective â to destabilize the Duvalier regime. Released in early 1966, and made into a major film starring Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor in the following year,

The Comedians

was one of his finest novels, and it created exactly the storm of publicity that Greene had hoped for. The world could not turn its eyes from the horror.

In the years that followed Diederich continued to advise Greene on political developments in Latin America. He eventually engineered Greene's visits to Panama where the novelist became a trusted friend of General Omar Torrijos, the strongman who was trying to map out a social-democratic future for his country. Greene's travels with Diederich â by then the Central American correspondent for

Time

magazine â led to close contacts with Daniel Ortega, Tomás Borge, Ernesto Cardenal and other Sandinistas in Nicaragua, as well as with Fidel Castro in Cuba.

Through all this, his guide and political adviser was Bernard Diederich, whose journalism and books made him, as Greene put it the introduction to Diederich's own book

Somoza and the Legacy of US Involvement in Central America,

an âindispensable' historian for the region. Bernard Diederich observed the day-to-day movements of one of the century's great novelists in some of his most important âinvolvements'. Himself a figure of quiet heroism, Diederich understood the broad and terrible context of Greene's work through these years, and he knew intimately the people who stood just beyond the pages of Greene's books. No writer is better placed to tell of Graham Greene's political engagements in the second half of his career â indeed, little of what follows was known to Greene's official biographer.

A work of observation and interpretation and, even more, a work of friendship, Bernard Diederich's political biography of Graham Greene is one of the most important accounts ever written about this author. It is a unique record, and we are lucky to have it.

Richard Greene

Editor,

Graham Greene: A Life in Letters

2012

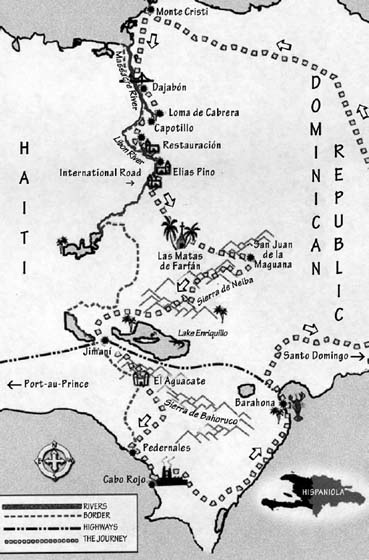

A map of part of the island of Hispaniola showing the border area between Haiti and the Dominican Republic; the route of the journey taken by Graham Greene, Bernard Diederich and Fr Jean-Claude Bajeux in 1965 is marked.

Graham Greene in Haiti

1 | SEEDS OF FICTION

In Haiti they say life begins long before birth and that death is not an end but a continuation of the same long coil threading back to the beginning. The story of Haiti is certainly tragic, but unlike a work of fiction it has no end. It continues today with misery pouring down on a proud and independent people. The everyday Haitian's answer to violence, poverty, sickness and death is always the same:

bon Die sel ki kone,

only God knows. They say it with a hopeful frown and an uncertain smile. And while they speak of God â Catholicism and Christianity are prevalent in Haiti â it is Voodoo that offers the people hope; it offers them immortality. This is the magic of Voodoo. It's also the power of great fiction. It can immortalize a character, a story or a deep truth. This is why, on an overcast afternoon in January 1965, I found myself standing by the arrival gate at Santo Domingo's Las Americas airport waiting for Graham Greene.

I wanted Graham to write a book about Haiti. Like many Haitians I was at war against the dictatorship of François âPapa Doc' Duvalier. Two years earlier I had been forced into exile with my Haitian wife, Ginette, and our infant son after living in Haiti for almost fourteen years. My first seven years in Haiti were full of the magic that some like to call the old Haiti. It was a time when the country was experiencing a cultural renaissance. There was virtually no crime. While the deforestation and over-population was noticeable, it wasn't nearly as extreme as it is today. It was a clean, charming place populated with beautiful and interesting people. There was something intimate and exotic about Haiti. It was a popular tourist destination, particularly with artists, bohemians and the Hollywood set, which is how I came to meet Graham in the first place. Marlon Brando, Anne Bancroft and Truman Capote all visited the island during this time.

En route

to the South Pacific I had sailed into Port-au-Prince, quit the sea to search for my stolen camera, fallen in love with Haiti and, after a short stint working at an American-owned casino, started an English-language weekly newspaper, the

Haiti Sun,

in 1950. Soon I picked up stringing work from the US and British media. Between the late 1940s and the mid-1950s Haiti possessed more than hope and charm: it had magic.

But the last seven years had been a horrible nightmare. In 1957, after

Duvalier won the presidency, the country slowly descended into a state of fear as Papa Doc tightened his grip on power and declared himself President-for-Life. Many of my friends and colleagues were killed or disappeared. While I was busy reporting on the atrocities for the international media, I had to be careful of what I published in my own paper. I had to avoid the attention of Duvalier and his henchmen, the Tontons Macoutes. Whenever the government censors blinked I would telex or cable my stories, which were published, many times anonymously, in

Time, Life,

the

New York Times,

on NBC News and in the Associated Press. For seven years I walked a fine line, knowing that if Papa Doc found out I had written something critical I was certain to join the growing ranks of the âdisappeared'.

As I watched Graham's tall, lean figure make its way through customs, his blue eyes cutting across the airport with a hint of suspicion, I wondered if, indeed, he had the power to change Haiti. Could he bring down Duvalier? And, more to the point, would he write a book about Haiti?

Graham was sixty-one. His hair was thinning slightly, but he looked as robust as ever. He was dressed in tan linen trousers and a dark coat. His pale complexion stood out from the crowd of tourists and Dominican nationals arriving on the Pan American flight from Canada, where he had spent Christmas with his daughter Caroline.

We didn't need to shake hands: a smile sufficed. As he thanked me generously for meeting him, I could feel his energy. He was so eager at the prospect of our trip he was giddy with excitement.

âIt's wonderful to be back in the Caribbean,' he said when he came out of customs. Then he took me by the arm. âI hope I'm not keeping you from your work.'

âNo, not at all,' I replied.

He seemed to forget I had been the one to suggest we take a trip along the HaitianâDominican border. He stopped, and now he smiled at me again and slapped me on the back of the shoulder as we walked out of the airport. âSo when do we start?'

Hearing Graham talk this way, overflowing with enthusiasm, thrilled me. I had last seen him in August 1963. The British Ambassador in Santo Domingo had telephoned me with a message from Greene. He was coming to the Dominican Republic from Haiti and wanted to know if I could pick him up at the airport. I was taken by surprise. I hadn't seen Graham since we spent a week together in Haiti in 1956. I never imagined we would cross paths again.

The Graham Greene I'd met in 1963 looked frazzled and slightly unkempt. He arrived with little luggage and a painting by Philippe-Auguste, which he said he had purchased with his winnings from a night at a deserted casino in Port-au-Prince. He was unusually quiet and let out a deep sigh as he squeezed

into the seat of my Volkswagen Beetle. It was clear he was relieved to be out of Haiti. As we drove out of the airport he rested his arm out the window and took in the smell of the summer rains and the burning charcoal from the cooking fires of the neighbourhood

colmados.

âI thought I was doomed to stay,' he said after a long silence. His face was stark and serious. He didn't look at me; instead he stared blankly at the blue of the Caribbean as we drove along Autopista Las Américas.

âI felt something was going to happen. I was so sure of it. I thought I'd be stopped at the last minute. And just as I was about to board the plane someone pressed a letter into my hand and whispered, “Please, give this to Déjoie in Santo Domingo.” I was afraid it could be a trap; perhaps a

provocateur.

I refused.' He looked at me and tightened his grip on the bag he had on his lap. I understood. The risk was too great. He was concerned about his notes. âYou think I did the right thing?'

âI'm certain of it,' I said. Louis Déjoie had lost the presidential election to Papa Doc in 1957. Like most of Duvalier's opponents he ended up in exile in the Dominican Republic where he was trying to position himself as the leader of the Haitian exile community. But the former senator had no support among the exiles. He was alone. All he could do was continually to denounce the exile groups as Communist. At one point he got us all arrested.

Graham said he had gone back to Haiti on assignment for the London

Sunday Telegraph.

He had been reading stories of the growing terror in Haiti and wanted to see it for himself. âI had a hunch the exiles might launch an attack on Duvalier from the Dominican Republic,' he said. The promise of action had lured him back to the island.

I didn't tell Graham that I had been keeping track of his visit to Haiti. Diplomat friends returning from visiting Port-au-Prince always brought me a bundle of Haitian newspapers. Aubelin Jolicoeur's column âAu Fil des Jours' (âAs the Days Go By') in

Le Nouvelliste,

of 13 August 1963, read, âThe great writer Graham Greene is here to write an article on Haiti for the

Telegraph

of London. One of the greatest writers in the world, Graham Greene was welcomed to Haiti by the

chargé d'affaires

of Great Britain, Mr Patrick Niblock, and Aubelin Jolicoeur.' Jolicoeur had worked for my newspaper in the 1950s. Modesty was not one of his qualities. He was a fixture at the Grand Hotel Oloffson and became Greene's real-life model for the character of Petit Pierre in

The Comedians.

Graham's physical description in the novel was dead on: âEven the time of day was humorous to him. He had the quick movements of a monkey, and he seemed to swing from wall to wall on ropes of laughter.' But it was his assessment of who Petit Pierre really was that was telling: âHe was believed by some to have connexions with the Tontons, for how otherwise had he escaped a beating-up or worse?' Years later Graham confessed to me

he always suspected Jolicoeur was a spy for Duvalier. I never believed that. Like many Haitians he was a survivor. What other option did he have?

After listing Graham's published works Jolicoeur noted, âThis is Mr Greene's third visit to Haiti and he will spend ten days at the Hotel Oloffson. He has expressed a desire to meet Dr François Duvalier. We wish the author of

The Power and the Glory,

considered a great work, welcome.'

I dropped Graham off at the British Ambassador's residence. The following evening he came to our home in Rosa Duarte for dinner. I had also invited Max Clos, of

Le Figaro,

who had covered the war in Indochina at the same time as Graham and who had been on a reporting trip to Haiti.

That night Graham behaved in a way that was completely out of character. He began acting, mimicking Papa Doc's Foreign Minister. I had known him to be reserved, direct, quiet. I had never seen him this animated. He displayed a wonderful sense of mimicry.

âNo interview is possible,' he said, playing the part of Haitian Foreign Minister René Chalmers. âI regret, Monsieur Greene, the President is not receiving the foreign press at this time.' He nailed the accent perfectly. âYou know Chalmers,' he laughed. âHe's this huge frog-like man who sits behind his desk at the end of a long, narrow room and closes his eyes as he speaks.' Then he went on mimicking the minister. âAh, Monsieur Greene, it is not possible at this time to travel to the north. It is for your own safety, you understand. If safety considerations are to be taken into account every time a journalist covers a story, there would be no coverage whatsoever.' Coverage, we both knew, was precisely what Duvalier didn't want.