The Setting Sun (9 page)

Authors: Bart Moore-Gilbert

While the adults discuss, the boy wanders off. He’s fascinated by these temporary wet-season settlements. The fishermen make platforms of reeds to sleep on, within a scaffolding of branches, lashed together with strips of bark, on which they dry their harvest. Mainly it’s catfish, with flat, wide heads and long whiskers. In the broiling sun they shrink, turning and leather-brown, like stinking sandals. Around their camps, the reeds stretch for miles in ankle-deep water from the flooding Ugalla. The boy loves to slosh through them in his new gumboots, replacements for the ones stolen from outside his tent on the floor of the Ngorongoro Crater. His father hadn’t believed him when the boy claimed to have heard snuffling during the night. Only when they continued the hyena cull the following day and one gumboot was found in an elderly female’s stomach did his father apologise. The next time he went to Arusha, he bought the best replacements he could find

.

Later, the fishermen take them to see the latest wave of migratory birds. Crouching behind a tussocked ridge from where the flat opal surface of the seasonal lake stretches away, the boy’s father gets out his decoy, a black tube like a relay baton. A few toots bring some Egyptian geese scooting over the water, brown and white with iridescent green heads and a blue wing chevron. But the boy isn’t all there. He keeps having flashbacks to the elephant’s dreadful gash, and smoulders with anger against those who did it

.

When they get back to camp, it’s growing dark. There’s laughter and excitement amongst the scouts building the fires

.

Strips of elephant meat have been set out to cure on frames like the ones the fishermen use. Light-skinned Salim’s back, and the Land Rover’s gone one last time to fetch Daoudi, the tracker and Hamisi Sekana. They’ve found the poachers’ camp and are bringing someone in. The boy and his father barely have time to measure the tusks of the young elephant, still partly encased in a crimson honeycomb of shattered jawbone, when they see headlights bumping towards them. Soon three figures emerge from the shadows. Hamisi leads forward a small, undernourished man wearing only filthy shorts and sandals made from old tyre treads, wrists handcuffed behind his back. Despite his bare, pumping pigeon-chest and pronounced limp, the boy takes a violent dislike to him. It’s the sly eyes and obsequious smile. On each shoulder, Daoudi bears a tusk. These must be forty pounds each

.

‘We found the camp and this man hiding in the bush nearby. There was this ivory. And traps.’

The murderous wires tinkle and glint in the firelight where Hamisi sets them down. He’s smiling. It’s a job well done, and the boy’s father tells him so. Then he compares the first noose recovered with these ones

.

‘You see,’ he shows the boy, ‘they’ve got five twists around the neck. Made by the same person.’

‘He’s not from round here,’ Hamisi interjects. ‘He says he comes from the north, near Mwanza. But his Swahili is

shenzi.’

The boy spotted some of the man’s, too, has mistakes. His father nods and begins to ask questions. At first his tone is conversational, as if they’ve all just met in friendlier circumstances. What’s the man’s village, his tribe, his father’s name, those of his relations? The man shifts from foot to foot, as if his bad leg’s giving him trouble. At times he’s defiant, more often ingratiating. He claims to have been travelling south and stumbled on the deserted camp. Hearing the scouts approach, he hid nearby, fearing the owners were returning. He knows nothing about the tusks or nooses

.

‘Where were you travelling to? Who were you visiting and where? Why didn’t you go by the road?’ Then the questions become more general

.

The boy’s becoming increasingly angry. Who cares what the president’s wife is called? With every faltering answer, as the suspect mangles the Swahili words, he knows the man’s lying. Why isn’t the questioning more direct?

‘Have you ever seen an animal caught in a noose?’ his father eventually asks the man, almost as an afterthought. ‘Can you imagine what it feels?’

The suspect denies it emphatically. Hamisi’s face twists into a sneer. The boy’s finding it hard to control himself. He wants to beat the man, make him confess and apologise. Put his bad leg in a wire noose and see how he makes out. Then his father begins to ask the identical questions he began with, in the same matter-of-fact tone. The boy’s furious. Why’s his father wasting time? Adults can be so unfair sometimes. His father thrashed him once for twisting their pet monkey’s tail, yet now he’s smiling at this man, politely inquiring after his personal affairs when the suspect’s caused the elephant intolerable suffering. Suddenly his father sits up straighter, his tone steely at last

.

‘The first time you said your village was to the east of Mwanza, now it’s the other side. If you came from anywhere near Mwanza you’d know

Binti

Nyerere’s name. Do you take me for an

mpumbafu?’

Daoudi laughs derisively. It’s the prisoner who’s made a fool of himself. Traps don’t have to be made of wire, the boy realises, with a burst of admiration. In the firelight, his father’s face flickers lividly. Surely he’s going to give the man a thrashing now? Perhaps the suspect fears the same thing, for his expression suddenly crumples. Looking down, he confesses to coming across Lake Tanganyika three weeks earlier, from Rwanda, where unspeakable things are happening

.

‘We are poor men, bwana, we have been chased from our homes. What can we do?’

He explains that the gang was paid by an Indian they met in Kigoma, who smuggles ivory to the Far East. The boy’s father is calm again. He listens attentively

.

‘So many of these buggers are coming over now,’ he mutters

.

‘What’ll happen to him?’ the boy asks later, tucked up under his mosquito net, still aggrieved

.

His father stirs. ‘We’ll take him up to the police post in Mpanda. They’ll do the paperwork and send him on to court in Tabora.’

‘And if he denies it in front of the judge?’

‘You have to collect the evidence. Then it’s for other people to decide,’ his father explains, as if to an apprentice. ‘We need to catch the rest of the gang and persuade him to give evidence against them. If that happens, he’ll be fined and they’ll probably get a couple of years.’

‘That’s more than the poor flump will have.’ The boy’s face burns vengefully again

.

‘Well, at least she’s out of her misery. Think about something else or you’ll have nightmares.’

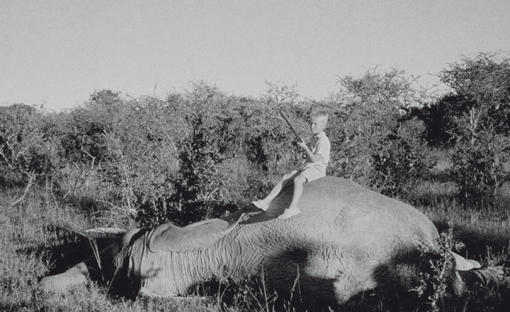

Author sitting on rogue elephant shot by Bill, holding a rifle, c. 1961

.

‘I want to smash that man.’

‘Yes, I understand. But we’ll be needing his help.’ The boy’s father sits up. ‘Did you leave your Wellingtons outside?’

‘Should I bring them in?’

‘No thanks, old chap. I doubt the Ugalla hyenas could face the smell of your toe jam. They’re not as brave as up at the Crater.’

Before the rumbling laugh dies down, the boy’s asleep, exhausted by the emotion of another long day

.

At first I’m reassured by my recollections. Surely, if Bill had the traits that Shinde describes, he’d have sought fresh opportunities to indulge them in Africa. Yet he didn’t join the police in Tanganyika, which would have been a logical step. Nonetheless, there wasn’t, I now realise, such a divorce between Bill’s career here and his role as a game ranger. He caught the man out using interrogation techniques he’d no doubt learned as an IP officer. Tracking poachers probably involved the same sort of skills as hunting the Parallel Government. Catching malefactors, gathering evidence, consigning them to justice, was consonant with his earlier vocation. However, if Shinde’s account is true, it seems strange that Bill didn’t take the opportunity to rough up the poacher. It’s what I’d been hoping he’d do. Perhaps he held back because I was there. I didn’t accompany him every time he was in the bush. Still, if Bill was that kind of man, word would surely have got around. Yet I never saw a glint of fear in Kimwaga’s eyes, or a flicker of caution in Hamisi Sekana’s. If he was a constitutionally violent man, I’d have expected them to show some reserve. Even with the cook, Bill used only enough force to protect Eunice.

But then the doubts set in. Shinde’s narrative seemed unimpeachably scholarly. I’m suddenly angry and disgusted with Bill. Did he think such actions would pass unremarked at the time, or escape the subsequent searchlight of History? It’s as if he’s compromised me as well. In turn I’m angry with myself

for my naivety. For as long as I knew so little about Bill’s career in the subcontinent, I didn’t waste much time thinking about it. Once decided on coming to India, however, I did follow up some of Professor Bhosle’s leads. But I was too busy to do more than read a couple of books on Sindh.

The story of Britain’s acquisition of the region is another dispiriting chapter in our imperial past. Ignoring long-standing friendship treaties with local chieftains, Charles Napier annexed it in 1843 to Bombay Presidency – an act of treachery for which he was later knighted. His expedition was partly mounted, it seems, to compensate for the catastrophic failure of the recent attempt to invade and subdue Afghanistan. Sindh’s later history under the Raj is hardly more appetising. In the early 1940s, under the leadership of their charismatic religious leader, the Pir Pagara, certain Muslim communities in Sindh pronounced themselves

hur

, or free of imperial control. The British declared marshal law against these ‘Mohammedan fanatics’, herded large numbers into concentration camps and introduced a shoot-on-sight policy for those who refused to go. The Pir Pagara was hanged in March 1943, after a show trial, although the Hurs continued to agitate long afterwards.

However, I could find no reference to Bill in these texts – more to my relief than disappointment, given the story I uncovered. With time at a premium before departure, the issue of what he was doing in Satara would have to wait until I reached Mumbai. Indian friends in London reminded me that after Gandhi’s ‘Quit India’ speech in early August 1942, there were mass arrests of nationalist activists in Bombay and other Indian cities. But they weren’t aware that significant violence was involved – on either side – during the round-up and its aftermath. Nor that there was much agitation outside the urban areas.

Now I wonder if I haven’t been guilty of self-deception, even bad faith. Perhaps it’s been a little too convenient that Bill’s Indian career remained shrouded in mystery. As a professor of

Postcolonial Studies, I’m well aware of the long tradition of negative literary representations of the British Empire. More specifically, I’m familiar with the disobliging portraits of the Indian Police drawn by writers like George Orwell and Paul Scott. In Orwell’s

Burmese Days

, Flory is a pathetic and primarily self-destructive character, undone in the end by his inability to escape the straitjacket of the racial thinking of his time. By contrast, Superintendent Merrick in Scott’s

Raj Quartet

is one of the most chillingly manipulative and self-serving characters in postwar British writing, someone who grossly abuses his position to advance his own interests.

When I read these works years ago, I did sometimes have uneasy feelings about Bill’s career, wondering how accurate such depictions were of the declining standards of the service as the Raj sped towards dissolution, in the period when my father was in the subcontinent. But Merrick, at least, was exceptional, a rogue officer, acting out perverse private notions of justice or simply satisfying sadistic urges. Otherwise it would be hard to explain the disapproval shown him by other characters, as well as Scott’s narrative voice. So I didn’t ever connect someone like him with Bill, even as Scott helped me understand that the IP was British India’s first line of defence and a prime instrument of its control.

It’s a hot night, and I’m so restless that when I eventually get back to my hotel, I spend much of the night in the shower. As I stand under the piddling dribble, I revolt against the clashing image-repertoires I now have of Bill. Can the father I so loved and respected as a child really have been capable of the excesses Shinde describes? How could the person who gave his life trying to help refugees have committed such crimes? The figure in Rajeev’s photo, with which I formed such a powerful connection earlier in the day, now feels like a repulsive interloper amongst my memories. If Shinde’s allegations are true, Bill’s behaviour is against the rules of any civilised society – even if these standards have been subject to still more

merciless assault in the era of Blair and Bush, of Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib. Perhaps the IP was simply a vile and brutal instrument of occupation. But if so, it’s strange I’ve been made so welcome everywhere, despite my openness about Bill’s years in the force. And even odder that such a gentle and intelligent man as Rajeev Divekar seems to so admire the service.