The Sexual History of London (7 page)

Read The Sexual History of London Online

Authors: Catharine Arnold

A question mark hangs over Jane's subsequent fate. The popular perception is that she lived on, âlean, withered and dried up', according to Sir Thomas More, and ended her days begging on the streets of London, and gave her name to âShoreditch', the spot at which she died. But it seems unlikely that Jane died in poverty. Thomas Lyneham was a wealthy man, and even Sir Thomas More, when he met Jane in old age, reported that she had a soft tender heart and that the remnants of her beauty still shone through the ravages of time. The less sensational facts are these: Jane died at the age of eighty-two, a considerable age in those days, and was buried in Hinxworth Church, Hertfordshire, where her effigy remains to this day. She was a remarkable woman, having survived the back-stairs politics of a savage age, when Richard III cut a murderous swathe to the throne and the first Tudor monarch, Henry VII, subsequently dispatched all Plantagenet opposition. To have married again, died of old age and be buried in a quiet country church was quite an achievement for our demi-mondaine, first of a long and fascinating line of celebrity mistresses.

As Jane breathed her last peacefully, far from London and the court, a new and terrifying development in London's sexual history had made itself manifest: a mysterious, disfiguring and potentially lethal disease, against which the forces of both Church and state seemed powerless.

âDetestable Vice and Synne'

Henry VIII has never been associated with piety or sexual abstemiousness. Indeed, the notorious Tudor's name is still synonymous with self-indulgence: hunting, dancing, eating, drinking and, most famously of all, wenching. And yet, in a move which now seems extraordinary, King Henry introduced two draconian pieces of legislation ostensibly aimed at curtailing the pleasures of the flesh. In 1546, he ordered the closure of London's brothels. And prior to this, in 1533, he ensured that the Buggery Act would be steered through Parliament. In this chapter, we will examine Henry's motivation for this legislation, and the success, or otherwise, of the venture.

First, let us turn to the attempt to close the brothels. In April 1546, Henry VIII issued a strict edict âputting down the stews'. This was announced in the streets by a herald at arms, accompanied by blasts on a trumpet. The proclamation stated that any brothel keeper who ran one of the distinctive whitewashed houses must cease trading immediately. He or she was banned from entertaining clients or selling victuals.

1

And allied trades were destined to feel the pinch: in order to deter punters pouring into Bankside, Moorgate, Fleet Street and Chancery Lane, Henry VIII outlawed bear-baiting and dog fighting and closed the establishments where these entertainments took place. Bearing in mind Henry's permissive personal life and taste for cruelty, it seems extraordinarily hypocritical to have deprived Londoners of their traditional pleasures, however barbaric these seem to modern readers. It appeared unlikely that Henry was bowing to pressure from his subjects regarding lawlessness and antisocial behaviour. He had not been noted for listening to the wishes of his people, let alone acting on them, and at that historical period it was unlikely that his decision was informed by a sudden revelation concerning the issues of sex slavery or animal rights. Moreover, Henry himself was a veteran of âWinchester Garden', never missing an opportunity to frolic with the âgeese' procured for him by his pimp, the devious Archbishop Gardiner. So what was the real explanation for Henry's decision to close the stews?

For the answer, we must travel to Renaissance Italy and enter the consulting rooms of Dr Pedro Pintor (1423â1503), physician to Pope Alexander VI, the âBorgia Pope' (who, you will recall, was in the habit of getting prostitutes to crawl around the floor of his palace, squabbling over pieces of jewellery). Dr Pintor had identified an horrific sexual plague, the victims of which âlanguished' with âan obscene disease: dire flames upon their vitals fed within, While Sores and crusted Filth prophan'd their Skin'.

2

Whilst Dr Pinto would have been familiar with gonorrhoea, or âthe burning', characterized by severe inflammation of the urethra causing severe pain on urination (hence the name), he now encountered a ruthless and ultimately deadly condition.

In March 1493, Dr Pintor had noted the first case of the

morbus gallicus

, or âFrench disease', in Rome, and claimed that the French army had brought it into Italy. Over the next two years, the disease spread like wildfire across Europe, as the inevitable consequence of military campaigns. When the French army occupied Naples in February 1495, many French soldiers were infected, so they in turn decided to call it

mal de Naples

, âthe sickness of Naples'. In August 1495, the Emperor Maximilian issued an edict referring to the disease as

malum franciscum

, and, when the French returned home in 1495, they spread it across their homeland. As Voltaire put it: âwhen the French went hotfoot into Italy they easily won Naples, Genoa and the Pox. When they were driven out they lost Genoa and Naples, but they did not lose everything, for the Pox stayed with them!' âPox' (from âpocks' on the skin brought about by the ravages of infection) remained the popular name for the disease for years after.

3

The disease was officially recorded in Naples in January 1496; eight weeks later, the authorities in Paris made the first bid to control this menace to public health. But this proved impossible with promiscuous armies rampaging their way across Europe. Cesare Borgia caught it in France, and Pope Julius and many cardinals were also infected. The disease arrived in England around 1500. When it first occurred, doctors assumed this particularly vicious strain originated in the new American colonies, and had been brought back to Europe by Columbus's sailors. But, in 1521, the Veronese physician Girolamo Fracastoro gave the condition a name in his poem

Syphilis sive morbus gallicus

(âSyphilis, or the French disease'), which concerns the ordeal of a Greek peasant named Syphilus. Syphilus had angered Apollo and was punished with ill health and dreadful ulcers all over his body, which were later cured by Mercury, the god of medicine.

Fracastoro expressed doubt that the disease had come from America, and the controversy over its origins continues to this day, with some experts claiming that it originated in pre-Columbian America, whilst others argue that it originated in Africa and spread as the result of the slave trade. A third theory suggests that the disease mutated at the end of the fifteenth century and became virulent due to the unusual movements of populations in the Age of Discovery.

4

Renaissance thinkers postulated a number of theories as to the origins of the disease, ranging from astrology to leprosy. The most bizarre theory of all was proposed by Francis Bacon in

Sylva Sylvarum.

According to Bacon, âthe French do report, that at the siege of Naples [1495] there were certain wicked merchants that barrelled up man's flesh (of some that had been lately slain in Barbary) and sold it for tunney [tuna fish]; and that upon that foul and high nourishment was the original of that disease. Which may well be; for that it is certain that the cannibals in the West Indies eat a man's flesh; and the West Indies were full of the pocks when they were first discovered.' In other words, Bacon is suggesting that syphilis originated from cannibalism.

5

Whatever its origins, syphilis spread with deadly rapidity among a population with a low degree of immunity. This was compounded by the fact that it could be spread without sexual contact. A syphilitic barber, an infected cup or a kiss from a diseased person were all enough to pass on the disease.

6

Tragically, it could also be spread by breast feeding, which in an era of wet-nursing presented a grave risk to infant health, and to the health of a nurse, who could be infected by a syphilitic baby.

7

The strain of syphilis decreased in severity over the course of the sixteenth century, most likely, Fabricius tells us, as a result of improved standards of living. But it was still a peculiarly unpleasant condition.

The physician Thomas Sydenham's description of the progress of the disease includes the graphic observations that the symptoms begin with a spot, about the size and colour of a measle, which appears in some part of the glans, followed by a discharge from the urethra. As the pustule becomes an ulcer, the patient experiences great pain during erections, followed by the development of buboes, swellings of the lymph nodes, in the groin. Then come splitting headaches, pains in the arms and legs, while crusts and scabs form on the skin. The bones of the skull, shin-bones and arm-bones are raised into hard tubers, and, worst of all, the cartilage of the nose is eaten away so that the bridge sinks in and the nose flattens.

8

One author noted the case of a man who âbeing long sicke of the poxe had two tumours and an ulcer in his nose, at the which everie day there came foorth great quantitie of stinking and filthie matter'. This grim description depicts one of the most horrible lesions of syphilis, in which nasal bones are destroyed by

gumma

, or gummy tumours. Syphilis attacks the mucous membranes and soft tissue, eating away the nose and in serious cases exposing the brain to the air.

9

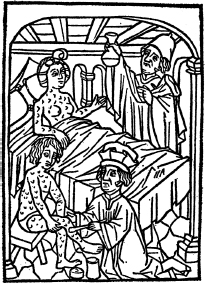

Treatment of a syphilitic couple with mercury balm, a common medication during the fifteenth century.

This was an extreme example of syphilis; just as disturbing were the symptoms that went undetected. Victims were not always aware that they had been infected, and the disease took time to reveal itself: patients might feel well for up to four months before the syphilitic symptoms appeared, in the form of a âdosser' or syphilitic bubo, agonizing ulcers that ate away the skin. But treatment was just as painful. The traditional remedy for all skin diseases such as scabies, psoriasis and leprosy was mercury, or

Unguentum Saracenium

, an ointment invented by the Arabs (hence the name âSaracen') and readily available in Europe.

10

This was a primitive form of chemotherapy, in which the mercury burned off the skin tumours, although it was not an effective long-term cure, as it did not destroy the infection and it was highly toxic.

An alternative treatment came in the form of guaiac, a wonder drug from the New World which sailors claimed would cure syphilis without the gruesome side effects of mercury. This substance derived from the guaiacum tree, a heavy, ebony-like wood, as black as ink, and was administered in a tincture in a sweat room, with the patient confined in stinking conditions for up to a month. The other remedy, which involved excising the sores and cauterizing the wound, would have been excruciating. If the disease had got a hold, it became essential to seek out an expert surgeon for help. Dr Andrew Boord, a famous physician, advocated celibacy and abstinence: at the first stirrings of an erection, a man was advised to âleap into a grete vessel of cold water or putte nettles in the Codpeece about the yerde [penis] and the stones [testicles]', an extreme but doubtless effective method of cooling one's ardour.

11

Scapegoats for the spread of syphilis were not hard to find. In 1530, Dr Simon Fish, a Protestant divine, even told Henry VIII that promiscuous âRomish priests' were responsible for the spread of the disease, claiming that they âcatch the Pockes of one woman and bear them to an other; that be BURNT with one woman and bare it unto an other; that catch the Lepry of one woman and bare it to anotherâ¦' The use of the word âlepry' is significant here, as doctors at this time had difficulty in distinguishing the symptoms of syphilis from those of leprosy. Meanwhile, Dr Boord had established that âif a Man be BURNT with an Harlotte and doe meddle with an other Woman within a Day he shal BURN the Woman that he shal meddle withal'.

12

Nobody was safe. Henry VIII himself was a sufferer, and many historians have attributed his volcanic rages and outbursts of paranoia to tertiary syphilis (end-stage syphilis). The pox was no respecter of persons, and men of the Church were not immune. In 1553, Henry's pimp, Archbishop Gardiner, was afflicted with âthe Burning' while in 1556, Dr Hugh Weston, Dean of Windsor, was sacked for adultery, after being âbitten by a Winchester Goose and not yet healed thereof'. The gossip writer John Aubrey tells us that Francis Bacon's mother made Sir Thomas Underhill âdeafe and blinde with too much of Venus'

13

when she married him, those symptoms being synonymous with sexually transmitted disease. And as for Sir William Davenant, the dramatist, the unfortunate gentleman âgot a terrible clap of a Black handsome wench that lay in Axe-yard, Westminster, which cost him his Nose', although the episode was not without its consolations, as the woman in question inspired the character of Dalga in the play

Gondibert

.

14

Prostitutes were inevitably held responsible for the spread of syphilis and condemned as ârotten filthy harlots' by the male medical establishment. For the whores, sexually transmitted disease was an unavoidable consequence of their trade, given that they might have intercourse with over thirty men in a day. Regular inspections by the likes of Dr Boord did nothing to protect them. Perfunctory examinations, lasting only a few minutes, were carried out with unwashed instruments by doctors with dirty hands. These health checks probably did as much to spread syphilis as the sex act itself. As it swept through London, Henry VIII had only one option: to close the brothels in an attempt to contain the epidemic. Sadly, this early example of gesture politics was ineffectual. Behind closed doors, Jack continued to have Jill, the sex trade flourished, and Henry's court became one of the most notorious in Europe, throbbing with intrigues, conspiracies and secret marriages. There was also a notable degree of male homosexuality. And yet, in 1533, Henry had instructed his adviser, Thomas Cromwell, to steer a new act through Parliament: it was referred to as âthe Buggery Act' and would make âbuggery' a capital offence, âbecause there was not sufficient punishment for this abominable vice, committed with man or beast'.

15