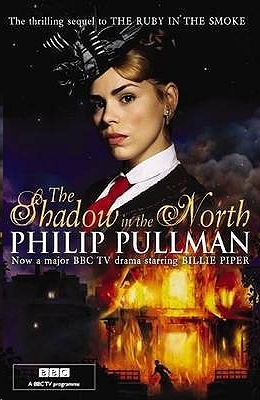

The Shadow in the North

Read The Shadow in the North Online

Authors: Philip Pullman

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Mysteries & Detective Stories, #Action & Adventure, #General, #Historical, #Europe, #Lockhart, #Sally (Fictitious character)

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

^Uinsolved ^1/lfly,sleries oj ike GJe

ea

One sunny morning in the spring of 1878, the steamship Ingrid Linde, the pride of the Anglo-Baltic shipping line, vanished in the Baltic Sea.

She had been carrying a cargo of machine parts and a passenger or two from Hamburg to Riga. The voyage had been uneventful; the ship was only two years old, well found and seaworthy, and the weather was gentle.

A day out from Hamburg, she was sighted by a schooner plying in the opposite direction. They exchanged signals. A barque, in the same part of the sea, would have seen her two hours later if the Ingrid Linde had kept to her course. But the barque saw nothing.

She vanished so swiftly and so completely that journalists of the time scented something as delicious as the lost continent of Atlantis, or the Mary Celeste, or the Flying Dutchman. They got hold of the fact that the chairman of the Anglo-Baltic line and his wife and daughter were on board, and filled the papers with accounts that it was the little girl's first voyage; that, on the contrary, she wasn't a little girl, but a young lady of eighteen, with a mysterious disease; that there was a

curse on the ship, laid by a former sailor; that the cargo consisted of a deadly mixture of explosives and alcohol; that in the captains cabin was a fetish idol from the Congo, which he had stolen from an African tribe; that in that part of the sea there was a gigantic and unpredictable whirlpool that appeared without warning and sucked ships down into a monstrous cavern at the center of the earth—and so on, and so on.

The story became quite famous. It was resurrected occasionally by writers who specialized in books with titles like Strange Horrors of the Deep.

But without facts, even the most inventive journalism peters out in the end, and there were no facts at all in this case—^just a ship that had been there one minute and vanished the next, and the sunshine, and the empty sea.

One cold morning a few months afterward, an old lady knocked on the door of an office in the financial heart of London. Painted on the door were the words S. LOCKHART, FINANCIAL CONSULTANT. After a moment, a voice—a female voice—called out "Come in," and the old lady entered the room.

S. Lockhart—the 5 stood for Sally; she was a remarkably pretty young woman of twenty-two, with blond hair and deep brown eyes—stood up behind her cluttered desk. The old lady took one step into the room and then hesitated, because standing on the hearth in front of the coal fire was the biggest dog she had ever

seen—as black as night and, to judge from its shape, a mixture of bloodhound, Great Dane, and werewolf

"Down, Chaka," said Sally Lockhart, and the great beast sat peaceRilly. His head still came up to her waist. "It s Miss Walsh, isn't it? How do you do?"

The old lady shook the hand held out to her. "Not altogether well," she said.

"Oh, I'm sorry," said Sally. "Please—sit down."

She cleared some papers off a chair, and they sat on either side of the fire. The dog lay down and put its head on its paws.

"If I remember correctly, I helped you with some investments last year," Sally said. "You had three thousand pounds—isn't that right? And I advised you to go for shipping."

"I wish you had not," said Miss Walsh. "I bought shares in a company called Anglo-Baltic, on your recommendation. Perhaps you remember."

Sally's eyes widened. Miss Walsh, who'd taught geography to hundreds of girls before she retired and who was a shrewd judge, knew that look well; it was the expression of someone who's made a bad mistake and has just realized it, and who is going to face the consequences without ducking.

"The Ingrid LindeJ' said Sally. "Of course. . . . And wasn't there a schooner that sank as well? I remember reading about it in The Times —oh, dear."

She got up and took a large book of newspaper clippings from the shelf behind her. While she leafed

through it Miss Walsh folded her hands in her lap and looked around the room. It was neat and clean, though the furniture was threadbare and the carpet worn, and there was a cheerful fire in the hearth, and a ketde hissing beside it. The books and the files on the shelves and the map of Europe pinned to the wall gave the place a businesslike look of purpose.

As for Miss Lockhart, she was looking grim. She tucked a strand of blond hair behind her ear and sat down, book open on her lap.

"Anglo-Baltic collapsed," she said. "Why didnt I notice . . . ? What happened?"

"You mentioned the Ingrid Linde. There was another ship—a schooner—that was lost too. And a third ship was impounded by the Russian authorities in St. Petersburg. I don't know why, but they had to pay an enormous fine to have the ship released. ... Oh, there were a dozen things. When you advised me to buy into it, the firm was prospering. I was delighted with your advice. And a year later it was finished."

"It changed hands, I see. I'm reading this for the first time; I cut out things like this so as to have them for reference, but I don't always have time to read them. Weren't they insured against the loss of the ships?"

"There was some complication; Lloyd's refiised to pay out—I didn't understand the details. There was so much bad luck, and so suddenly, that I almost began to believe in curses. In a malevolent fate."

The old lady was gazing into the fire, holding herself

perfectly upright in the worn armchair. Then she looked at Sally again.

"Of course, I know that's nonsense," she went on more briskly. "Being struck by lightning today doesn't prevent you from being struck again tomorrow; I'm quite familiar with the theory of statistics. But it's hard to keep a clear head when your money is vanishing and you can neither see why nor prevent it. I've got nothing left now but a tiny annuity. That three thousand pounds was a legacy from my brother and a lifetime's savings."

Sally opened her mouth to speak, but Miss Walsh held up her hand and went on. "Now, please understand, Miss Lockhart, I do not blame you. If I choose to speculate with my money, I have to take the risk that I shall lose it. And at the time, Anglo-Baltic was an excellent investment. I came to you in the first place on the recommendation of Mr. Temple the lawyer, of Lincoln's Inn, because I have a Ufetime's interest in the emancipation of women, and nothing pleases me more than to see a young lady such as yourself earning a living in this enterprising way. So I come to you again to ask for your advice: is there anything I can do to recover my money? I strongly suspect, you see, that it's not bad luck; it's fraud."

Sally put her book of clippings down on the floor and reached for a pencil and a notebook.

"Tell me everything you know about the firm," she said.

Miss Walsh began. She had a clear mind, and the facts were marshaled tidily. There weren't many of them; living as she did in Croydon, with no connections to the world of business, she'd had to rely on what she could gather from the newspapers.

Anglo-Baltic had been founded twenty years before, she told Sally, to profit from the timber trade. It had grown modestly but steadily, carrying furs and iron ore as well as timber from the Baltic ports and machine tools and other industrial products from Britain.

Two years ago, it had been taken over. Miss Walsh thought, or bought out—could that happen? She wasn't sure—by one of the original partners, after a dispute. The firm had leaped ahead, like a locomotive when the brakes are taken off; new ships were ordered, new contracts were found, a North Atlantic connection was built up. Profits rose remarkably in the first year under the new management, persuading Miss Walsh— and hundreds of others—to invest.

And then came the first of the apparendy unconnected blows that brought the company to liquidation in just as short a time. Miss Walsh had details about all of them, and Sally was impressed again by the old lady's command of the facts—and of herself, because it was clear that she was now on the brink of poverty, having expected to live out her retirement in modest comfort.

Toward the end of Miss Walsh's account, the name Axel Bellmann came into the story, and Sally looked up.

"Bellmann?" she said. "The match manufacturer?"

"I don't know what else he is," said Miss Walsh. "He didn't have any great connection with the company; I happened to see his name in a newspaper article. I think he owned the cargo the Ingrid Linde^2s carrying when it sank. She sank. I could never get used to calling ships she, could you? Some kind of machinery. Why do you ask? Do you know of this Mr. Bellmann? Who is he?"

"The richest man in Europe," said Sally.

Miss Walsh sat silently for a moment. "Lucifers," she said. "Phosphorus matches."

"That's right. He made his fortune in the match trade, I believe. . . . Though there was some kind of scandal, now that I think of it. I heard some gossip a year ago, when he first appeared in London. The Swedish government closed down his factories because of the dangerous working conditions in them."

"Girls with necrosis of the jaw," said Miss Walsh. "I've read about them, poor things. There are some wicked ways of making money. Did my money go into that, then?"

"As far as I know, Mr. Bellmann's been out of the match business for some time. And we don't know of his connection with Anglo-Baltic, anyway. Well, Miss Walsh, I'm grateful to you. And I can't tell you how sorry I am. I'm going to get that money back—"

"Now, don't say that," said Miss Walsh, in the sort of tone she must have used with frivolous girls who imagined they could pass examinations without working for

them. "I dont want promises, I want knowledge. I very much doubt whether I shall ever see that money again, but I am curious to know where it s gone, and I am asking you to find out for me."

Her manner was so severe that most young women would have quailed. But Sally wasn't like that—^which was why Miss Walsh had been able to come to her in the first place; and she said hody: "When someone comes to me for financial advice, I don't find it acceptable that I should lose all their money for them. And I don't want to be patronized when it happens. This is a blow to me, Miss Walsh, as much as it is to you. It's your money, but it's my name, my reputation, my livelihood. ... I intend to look into the affairs of Anglo-Baltic and see what happened, and if it's humanly possible, I shall recover your money and give it back to you. And / very much doubt that you'd refiise to take it."

There followed a glacial silence from the old lady, and a look that spoke thunder; but Sally sat firm and stared her out. And after a moment or two a twinkling warmth appeared in Miss Walsh's cy^s, and she tapped her fingers together.

"Quite right too," she said.

Both of them smiled.

The tension passed out of the room, and Sally got up. "Would you care for some coffee?" she said. "It's rather primitive to make it on the fire, but it tastes all right."

"Fd like that very much. We always used to make coffee on the fire when we were students—I haven't done it for many, many years. May I help?''

Within five minutes, they were talking like old friends. The dog was waked and made to move out of the way, the coffee was brewed and poured out, and Sally and Miss Walsh discovered the companionship that only women who'd had to struggle for an education could experience. Miss Walsh had taught at the North London Collegiate College, but she had never taken a degree; nor had Sally, for that matter, although she had studied at Cambridge and done well on the examination. The university let women do that much; they just didn't give them degrees.

But Sally and Miss Walsh agreed that the time would come, though it was hard to say when.

Eventually Miss Walsh stood up to go, and Sally noticed her neatly darned gloves, the frayed hem of her coat, and the brightly polished old boots, now badly in need of resoling. It was more than money she'd lost; it was the chance of living in modest comfort and without worry after a lifetime of helping others. Sally looked at her and saw that, despite her age and anxiety, the old lady's posture was firm and straight and dignified; Sally found herself standing straighter too.

They shook hands, and Miss Walsh turned to the dog, who had sat up expectantly when Sally stood.

"What an extraordinary beast," she said. "Did I hear you call him Chaka?"

"Chaka was a Zulu general," Sally explained. "It seemed appropriate. He was a present, weren't you, boy?"

She rubbed his ears affectionately, and the great animal turned and licked her hand with an enveloping tongue, his black eyes glowing with adoration.

Miss Walsh smiled. "I'll send on all the documents I've got," she said. "I'm most grateful to you, Miss Lockhart."

"I haven't done anything yet except lose your money for you," said Sally. "And it might turn out to be no more than it seems—things often do. But I'll see what I can learn."

Sally's background was unusual, even for one who lived an unusual life, as she did. She had never known her mother, and her father, a military man, had taught her a great deal about firearms and finance but very little about anything else. When she was sixteen he had been murdered, and she found herself drawn into a web of danger and mystery. Only her skill with a pistol had saved her—that, and a chance meeting with a young photographer named Frederick Garland.

With his sister, Frederick had been running their uncle's photographic business, but for all his skill with a camera, he was quite unable to manage the financial side of it. They were on the verge of ruin when Sally appeared—alone, and in deadly danger. In exchange for their help, she took over the running of the business,

and her talent for bookkeeping and accounts had saved them from bankruptcy.

The business had prospered. Now they employed half a dozen assistants, and Frederick was able to turn his attention to private detection, where his real interest lay. In this he was helped by another old friend of Sallys—Jim Taylor, who'd been an office boy in her father s firm and who had a taste for sensational novels of the sort known as penny dreadfuls and the most scurrilous tongue in the city. He had a vivid imagination and a quick ear, and he'd developed an actor's ability to vary his native Cockney accent to fit a multitude of circumstances. He was two or three years younger than Sally. In the course of their first adventure Jim and Frederick had fought, and killed, the most dangerous thug in London. They'd been nearly killed in the process, but each of them knew that he could rely on the other to the death.